Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Steve Macfarlane, Head of Clinical Services, Dementia Support Australia, & Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Monash University

This week, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved a drug called donanemab for people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Donanemab has previously been approved in a number of other countries, including the United States.

So what is donanemab, and who will be able to access it in Australia?

How does donanemab work?

There are more than 100 different causes of dementia, but Alzheimer’s disease alone accounts for about 70% of these, making it the most common form of dementia.

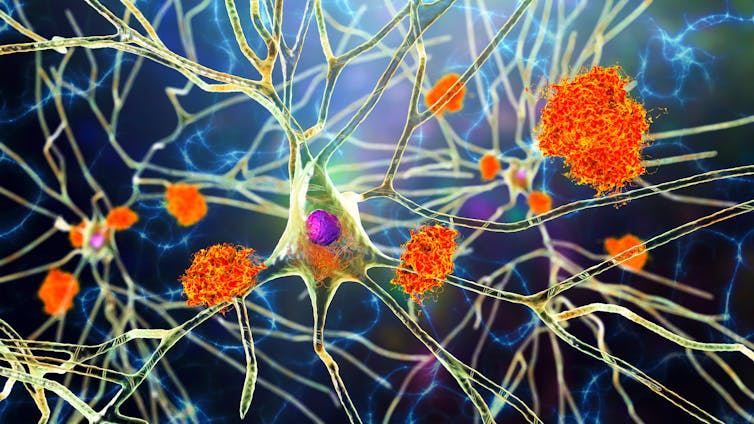

The disease is believed to be caused by the accumulation in the brain of two abnormal proteins, amyloid and tau. The first is thought to be particularly important, and the “amyloid hypothesis” – which suggests amyloid is the key cause of Alzheimer’s disease – has driven research for many years.

Donanemab is a “monoclonal antibody” treatment. Antibodies are proteins the immune system produces that bind to harmful foreign “invaders” in the body, or targets. A monoclonal antibody has one specific target. In the case of donanemab it’s the amyloid protein. Donanemab binds to amyloid protein deposits (plaques) in the brain and allows our bodies to remove them.

Donanemab is given monthly, via intravenous infusion.

What does the evidence say?

Australia’s approval of donanemab comes as a result of a clinical trial involving 1,736 people published in 2023.

This trial showed donanemab resulted in a significant slowing of disease progression in a group of patients who had either early Alzheimer’s disease, or mild cognitive impairment with signs of Alzheimer’s pathology. Before entering the trial, all patients had the presence of amyloid protein detected via PET scanning.

Participants were randomised, and half received donanemab, while the other half received a placebo, over 18 months.

Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

For those who received the active drug, their Alzheimer’s disease progressed 35% more slowly over 18 months compared to those who were given the placebo. The researchers ascertained this using the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale, which measures cognition and function.

Those who received donanemab also demonstrated large reductions in the levels of amyloid in the brain (as measured by PET scans). The majority, by the end of the trial, were considered to be below the threshold that would normally indicate the presence of Alzheimer’s disease.

These results certainly seem to vindicate the amyloid hypothesis, which had been called into question by the results of multiple failed previous studies. They represent a major advance in our understanding of the disease.

That said, patients in the study did not improve in terms of cognition or function. They continued to decline, albeit at a significantly slower rate than those who were not treated.

The actual clinical significance has been a topic of debate. Some experts have questioned whether the meaningfulness of this result to the patient is worth the potential risks.

Is the drug safe?

Some 24% of trial participants receiving the drug experienced brain swelling. The rates rose to 40.6% in those possessing two copies of a gene called ApoE4.

Although three-quarters of people who developed brain swelling experienced no symptoms from this, there were three deaths in the treatment group during the study related to donanemab, likely a result of brain swelling.

These risks require regular monitoring with MRI scans while the drug is being given.

Some 26.8% of those who received donanemab also experienced small bleeds into the brain (microhaemorrhages) compared to 12.5% of those taking the placebo.

Cost is a barrier

Reports indicate donanemab could cost anywhere between A$40,000 and $80,000 each year in Australia. This puts it beyond the reach of many who might benefit from it.

Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of donanemab, has made an application for the drug to be listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, with a decision pending perhaps within a couple of months. While this would make the drug substantially more affordable for patients, it will represent a large cost to taxpayers.

The cost of the drug is in addition to costs associated with the monitoring required to ensure its safety and efficacy (such as doctor visits, MRIs and PET scans).

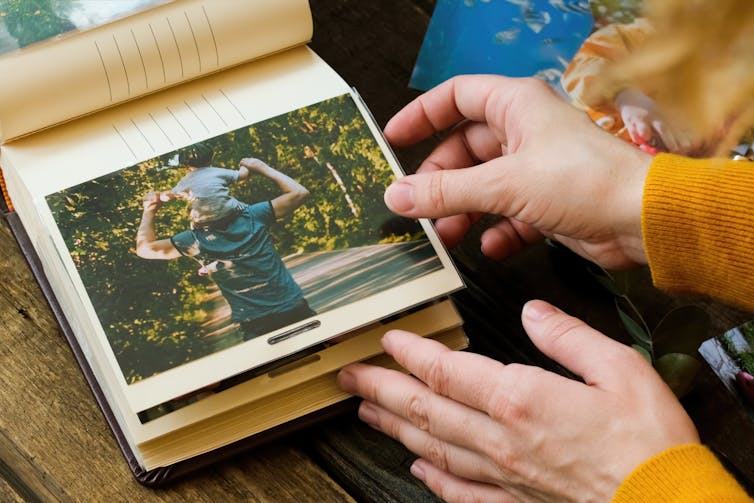

pikselstock/Shutterstock

Who will be able to access it?

This drug is only of benefit for people with early Alzheimer’s-type dementia, so not everybody with Alzheimer’s disease will get access to it.

Almost 80% of people who were screened to participate in the trial were found unsuitable to proceed.

The terms of the TGA approval specify potential patients will first need to be found to have specific levels of amyloid protein in their brains. This would be ascertained either by PET scanning or by lumbar puncture sampling of spinal fluid.

Also, patients with two copies of the ApoE4 gene have been ruled unsuitable to receive the drug. The TGA has judged the risk/benefit profile for this group to be unfavourable. This genetic profile accounts for only 2% of the general population, but 15% of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Improving diagnosis and tempering expectations

It’s estimated more than 400,000 Australians have dementia. But only 13% of people with dementia currently receive a diagnosis within a year of developing symptoms.

Given those with very early disease stand to benefit most from this treatment, we need to expand our dementia diagnostic services significantly.

Finally, expectations need to be tempered about what this drug can reasonably achieve. It’s important to be mindful this is not a cure.

![]()

Steve Macfarlane was an investigator on the donanemab trial, but received no direct compensation from Eli Lily for being so. Separately, has done consultancy work for Eli Lilly, for which he’s received payments.

– ref. The TGA has approved donanemab for Alzheimer’s disease. How does this drug work and who will be able to access it? – https://theconversation.com/the-tga-has-approved-donanemab-for-alzheimers-disease-how-does-this-drug-work-and-who-will-be-able-to-access-it-257321