Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jeff Kildea, Adjunct Professor Irish Studies, UNSW

In a remarkable coincidence, the first media reports about Spanish flu and COVID-19 in Australia both occurred on January 25 – exactly 101 years apart.

This is not the only similarity between the two pandemics.

Although history does not repeat, it rhymes. The story of how Australia – and particular the NSW government – handled Spanish flu in 1919 provides some clues about how COVID-19 might play out here in 2020.

Spanish flu arrives

Australia’s first case of Spanish flu was likely admitted to hospital in Melbourne on January 9 1919, though it was not diagnosed as such at the time. Ten days later, there were 50 to 100 cases.

Commonwealth and Victorian health authorities initially believed the outbreak was a local variety of influenza prevalent in late 1918.Consequently, Victoria delayed until January 28 notifying the Commonwealth, as required by a 1918 federal-state agreement designed to coordinate state responses.

Read more: Fleas to flu to coronavirus: how ‘death ships’ spread disease through the ages

Meanwhile, travellers from Melbourne had carried the disease to NSW. On January 25, Sydney’s newspapers reported that a returned soldier from Melbourne was in hospital at Randwick with suspected pneumonic influenza.

Shutdown circa 1919: libraries, theatres, churches close

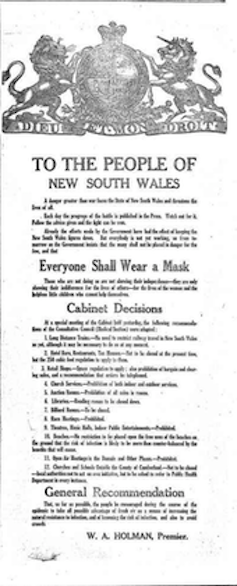

Acting quickly, in late January, the NSW government ordered “everyone shall wear a mask,” while all libraries, schools, churches, theatres, public halls, and places of indoor public entertainment in metropolitan Sydney were told to close.

It also imposed restrictions on travel from Victoria in breach of the federal-state agreement.

Thereafter, each state went its own way and the Commonwealth, with few powers and little money compared with today, effectively left them to it.

Generally, the restrictions were received with little demur. But inconsistencies led to complaints, especially from churches and the owners of theatres and racecourses.

People were allowed to ride in crowded public transport to thronged beaches. But masked churchgoers, observing physical distancing, were forbidden to assemble outside for worship.

Later, crowds of spectators would be permitted to watch football matches while racecourses were closed.

Spanish flu subsides

Nevertheless, NSW’s prompt and thorough application of restrictions initially proved successful.

During February, Sydney’s hospital admissions were only 139, while total deaths across the state were 15. By contrast, Victoria, which had taken three weeks before introducing more limited restrictions, recorded 489 deaths.

At the end of February, NSW lifted most restrictions.

Even so, the state government did not escape a political attack. The Labor opposition accused it of overreacting and imposing unnecessary economic and social burdens on people. It was particularly critical that the order requiring mask-wearing was not limited to confined spaces, such as public transport.

There was also debate about the usefulness of closing schools, especially in the metropolitan area.

But then it returns

In mid-March, new cases began to rise. Chastened by the criticism of its earlier measures, the government delayed reimposing restrictions until early April, allowing the virus to take hold.

This led The Catholic Press to declare

the Ministry fiddled for popularity while the country was threatened with this terrible pestilence.

Sydney’s hospital capacity was exceeded and the state’s death toll for April totalled 1,395. Then the numbers began falling again. After ten weeks the epidemic seemed to have run its course, but as May turned to June, new cases appeared.

The resurgence came with a virulence surpassing the worst days of April. This time, notwithstanding a mounting death toll, the NSW cabinet decided against reinstating restrictions, but urged people to impose their own restraints.

The government goes for “burn out”

After two unsuccessful attempts to defeat the epidemic – at great social and economic cost – the government decided to let it take its course.

It hoped the public by now realised the gravity of the danger and that it should be sufficient to warn them to avoid the chances of infection. The Sydney Morning Herald concurred, declaring

there is a stage at which governmental responsibility for the public health ends.

The second wave’s peak arrived in the first week of July, with 850 deaths across NSW and 2,400 for the month. Sydney’s hospital capacity again was exceeded. Then, as in April, the numbers began to decline. In August the epidemic was officially declared over.

Cases continued intermittently for months, but by October, admissions and deaths were in single figures. Like its predecessor, the second wave lasted ten weeks. But this time the epidemic did not return.

Read more: How Australia’s response to the Spanish flu of 1919 sounds warnings on dealing with coronavirus

More than 12,000 Australians had died.

While Victoria had suffered badly early on compared to NSW, in the end, NSW had more deaths than Victoria – about 6,000 compared to 3,500. The NSW government’s decision not to restore restrictions saw the epidemic “burn out”, but at a terrible cost in lives.

That decision did not cause a ripple of objection. At the NSW state elections in March 1920, Spanish flu was not even a campaign issue.

The lessons of 1919

In many ways we have learned the lessons of 1919.

We have better federal-state coordination, sophisticated testing and contact tracing, staged lifting of restrictions and improved knowledge of virology.

But in other ways we have not learned the lessons.

Despite our increased medical knowledge, we are struggling to find a vaccine and effective treatments. And we are debating the same issues – to mask or not, to close schools or not.

Meanwhile, inconsistencies and mixed messaging undermine confidence that restrictions are necessary.

Yet, we are still to face the most difficult question of all.

The Spanish flu demonstrated that a suppression strategy requires rounds of restrictions and relaxations. And that these involve significant social and economic costs.

With the federal and state governments’ current suppression strategies we are already seeing signs of social and economic stress, and this is just round one.

Would Australians today tolerate a “burn out”?

The Spanish flu experience also showed that a “burn out” strategy is costly in lives – nowadays it would be measured in tens of thousands. Would Australians today abide such an outcome as people did in 1919?

It is not as if Australians back then were more trusting of their political leaders than we are today. In fact, in the wake of the wartime split in the Labor Party and shifting political allegiances, respect for political leaders was at a low ebb in Australia.

A more likely explanation is that people then were prepared to tolerate a death toll that Australians today would find unacceptable. People in 1919 were much more familiar with death from infectious diseases.

Also, they had just emerged from a world war in which 60,000 Australians had died. These days the death of a single soldier in combat prompts national mourning.

Yet, in the absence of an effective vaccine, governments may end up facing a “Sophie’s Choice”: is the community willing and able to sustain repeated and costly disruptions in order to defeat this epidemic or, as the NSW cabinet decided in 1919, is it better to let it run its course notwithstanding the cost in lives?

Read more: Coronavirus is a ‘sliding doors’ moment. What we do now could change Earth’s trajectory

– ref. Lockdowns, second waves and burn outs. Spanish flu’s clues about how coronavirus might play out in Australia – https://theconversation.com/lockdowns-second-waves-and-burn-outs-spanish-flus-clues-about-how-coronavirus-might-play-out-in-australia-138429