ANALYSIS: By Myles Thomas

Kia ora koutou. Ko Ngāpuhi tōku iwi. Ko Ngāti Manu toku hapu. Ko Karetu tōku marae. Ko Myles Thomas toku ingoa.

I grew up with David Beatson, on the telly. Back in the 1970s, he read the late news which I watched in bed with my parents. Later, David and I worked together to save TVNZ 7 and also regional TV stations.

The Better Public Media (BPM) trust honours David each year with our memorial address, because his fight for non-commercial TV was an honourable one. He wasn’t doing it for himself.

He wasn’t doing it so he could get a job or because it would benefit him. He fought for public media because he knew it was good for Aotearoa NZ.

Like us at Better Public Media, he recognised the benefits to our country from locally produced public media.

David knew, from a long career in media, including as editor of The Listener and as Jim Bolger’s press secretary, that NZ’s media plays an important role in our nation’s culture, social cohesion, and democracy.

NZ culture is very important. NZ culture is so unique and special, yet it has always been at risk of being swamped by content from overseas. The US especially with its crackpot conspiracies, extreme racial tensions, and extreme tensions about everything to be honest.

Local content the antidote

Local content is the antidote to this. It reflects us, it portrays us, it defines New Zealand, and whether we like it or not, it defines us. But it’s important to remember that what we see reflected back to us comes through a filter.

This speech is coming to you through a filter, called Myles Thomas.

Commercial news reflects our world through a filter of sensation and danger to hold our attention. That makes NZ seem more shallow, greedy, fearful and dangerous.

The social media filter makes the world seem more angry, reactive and complaining.

RNZ’s filter is, I don’t know, thoughtful, a bit smug, middle class.

The New Zealand Herald filter makes us think every dairy is being ram-raided every night.

And The Spinoff filter suggests NZ is hip, urban and mildly infatuated with Winston Peters.

These cultural reflections are very important actually because they influence us, how we see NZ and its people.

It is not a commodity

That makes content, cultural content, special. It is not a commodity. It’s not milk powder.

We don’t drink milk and think about flooding in Queenstown, drinking milk doesn’t make us laugh about the Koiwoi accent, we don’t drink milk and identify with a young family living in poverty.

Local content is rich and powerful, and important to our society.

When the government supports the local media production industry it is actually supporting the audiences and our culture. Whether it is Te Mangai Paho, or NZ On Air or the NZ Film Commission, and the screen production rebate, these organisations fund New Zealand’s identity and culture, and success.

Don’t ask Treasury how to fund culture. Accountants don’t understand it, they can’t count it and put it in a spreadsheet, like they can milk solids. Of course they’ll say such subsidies or rebates distort the “market”, that’s the whole point. The market doesn’t work for culture.

Moreover, public funding of films and other content fosters a more stable long-term industry, rather than trashy short-termism that is completely vulnerable to outside pressures, like the US writer’s strike.

We have a celebrated content production industry. Our films, video, audio, games etc. More local content brings stability to this industry, which by the way also brings money into the country and fosters tourism.

We cannot use quota

New Zealand needs more local content.

And what’s more, it needs to be accessible to audiences, on the platforms that they use.

But in NZ we do have one problem. Unlike Australia, we can’t use a quota because our GATT agreement does not include a carve out for local music or media quotas.

In the 1990s when GATT was being negotiated, the Aussies added an exception to their GATT agreement allowing a quota for Aussie cultural content. So they can require radio stations to play a certain amount of local music. Now they’re able to introduce a Netflix quota for up to 20 percent of all revenue generated in Aussie.

We can’t do that. Why? Because back in the 1990s the Bolger government and MFAT decided against putting the same exception into NZ’s GATT agreement.

But there is another way of doing it, if we take a lead from Denmark and many European states. Which I’ll get to in a minute.

The second important benefit of locally produced public media is social cohesion, how society works, the peace and harmony and respect that we show each other in public, depends heavily on the “public sphere”, of which, media is a big part.

Power of media to polarise

Extensive research in Europe and North America shows the power of media to polarise society, which can lead to misunderstanding, mistrust and hatred.

But media can also strengthen social cohesion, particularly for minority communities, and that same research showed that public media, otherwise known as public service media, is widely regarded to be an important contributor to tolerance in society, promoting social cohesion and integrating all communities and generations.

The third benefit is democracy. Very topical at the moment. I’ve already touched on how newsmedia affect our culture. More directly, our newsmedia influences the public dialogue over issues of the day.

It defines that dialogue. It is that dialogue.

So if our newsmedia is shallow and vacuous ignoring policies and focussing on the polls and the horse-race, then politicians who want to be elected, tailor their messages accordingly.

There’s plenty of examples of this such as National’s bootcamp policy, or Labour’s removing GST on food. As policies, neither is effective. But in the simplified 30 seconds of commercial news and headlines, these policies resonate.

Is that a good thing, that policies that are known to fail are nonetheless followed because our newsmedia cater to our base instincts and short attention spans?

Disaster for democracy

In my view, commercial media is actually disaster for democracy. All over the world.

But of course, we can’t control commercial media. No-one’s suggesting that.

The only rational reaction is to provide stronger locally produced public media.

And unfortunately, NZ lacks public media.

Obviously Australia, the UK, Canada have more public media than us, they have more people, they can afford it. But what about countries our size, Ireland? Smaller population, much more public media.

Denmark, Norway, Finland, all with roughly 5 million people, and all have significantly better public media than us. Even after the recent increases from Willie Jackson, NZ still spends just $44 per person on public media. $44 each year.

When we had a licence fee it was $110. Jim Bolger’s government got rid of that and replaced it with funding from general taxation — which means every year the Minister of Finance, working closely with Treasury, decides how much to spend on public media for that year.

This is what I call the curse of annual funding, because it makes funding public media a very political decision.

National, let us be honest, the National Party hates public media, maybe because they get nicer treatment on commercial news. We see this around the world — the Daily Mail, Sky News Australia, Newstalk ZB . . . most commercial media quite openly favours the right.

Systemic bias

This is a systemic bias. Because right-wing newsmedia gets more clicks.

Right-wing politicians are quite happy about that. Why fund public to get in the way? Even if it it benefits our culture, social cohesion, and democracy.

New Zealand is the same, the last National government froze RNZ funding for nine years.

National Party spokesperson on broadcasting Melissa Lee fought against the ANZPM merger, and now she’s fighting the News Bargaining Bill. As minister she could cut RNZ and NZ On Air’s budget.

But it wouldn’t just be cost-cutting. It would actually be political interference in our newsmedia, an attempt to skew the national conversation in favour of the National Party, by favouring commercial media.

So Aotearoa NZ needs two things. More money to be spent on public media, and less control by the politicians. Sustainable funding basically.

The best way to achieve it is a media levy.

Highly targeted tax

For those who don’t know, a levy is a tax that is highly targeted, and we have a lot of them, like the Telecommunications Development Levy (or TDL) which currently gathers $10 million a year from internet service providers like Spark and 2 Degrees to pay for rural broadband.

We’re all paying for better internet for farmers basically. When first introduced by the previous National government it collected $50 million but it’s dropped down a bit lately.

This is one of many levies that we live with and barely notice. Like the levy we pay on our insurance to cover the Earthquake Commission and the Fire and Emergency Levy. There are maritime levies, energy levies to fund EECA and Waka Kotahi, levies on building consents for MBIE, a levy on advertising pays for the ASA, the BSA is funded by a levy.

Lots of levies and they’re very effective.

So who could the media levy, levy?

ISPs like the TDL? Sure, raise the TDL back up to $50 million or perhaps higher, and it only adds a dollar onto everyone’s internet bill. There’s $50 million.

But the real target should be Big Tech, social media and large streaming services. I’m talking about Facebook, Google, Netflix, YouTube and so on. These are the companies that have really profited from the advent of online media, and at the expense of locally produced public media.

Funding content creation

We need a way to get these companies to make, or at least fund, content creation here in Aotearoa. Denmark recently proposed a solution to this problem with an innovative levy of 2 percent on the revenue of streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney.

But that 2 percent rises to 5 percent if the streaming company doesn’t spend at least 5 percent of their revenue on making local Danish content. Denmark joins many other European countries already doing this — Germany, Poland, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, France and even Romania are all about to levy the streamers to fund local production.

Australia is planning to do so as well.

But that’s just online streaming companies. There’s also social media and search engines which contribute nothing and take almost all the commercial revenue. The Fair Digital News Bargaining Bill will address that to a degree but it’s not open and we won’t know if the amounts are fair.

Another problem is that it’s only for news publishers — not drama or comedy producers, not on-demand video, not documentary makers or podcasters. Social media and search engines frequently feature and put advertising around these forms of content, and hoover up the digital advertising that would otherwise help fund them, so they should also contribute to them.

A Media Levy can best be seen as a levy on those companies that benefit from media on the internet, but don’t contribute to the public benefits of media — culture, social cohesion and democracy. And that’s why the Media Levy can include internet service providers, and large companies that sell digital advertising and subscriptions.

Note, this would target large companies over a certain size and revenue, and exclude smaller platforms, like most levies do.

Separate from annual budget

The huge benefit of a levy is that it is separate from the annual budget, so it’s fiscally neutral, and politicians can’t get their mits on it. It removes the curse of annual funding.

It creates a funding stream derived from the actual commercial media activities which produce the distribution gaps in the first place, for which public media compensates. That’s why the proceeds would go to the non-commercial platform and the funding agencies — Te Mangai Paho, NZ On Air and the Film Commission.

One final point. This wouldn’t conflict with the new Digital Services Tax proposed by the government because that’s a replacement for Income Tax. A Media Levy, like all levies, sits over and above income tax.

So there we go. I’ve mentioned Jim Bolger three times! I’ve also outlined some quite straight-forward methods to fund public media sustainably, and to fund a significant increase in local content production, video, film, audio and journalism.

None of it needs to be within the grasp of Melissa Lee or Willie Jackson, or David Seymour.

All of it can be used to create local content that improves democracy, social cohesion and Kiwi culture.

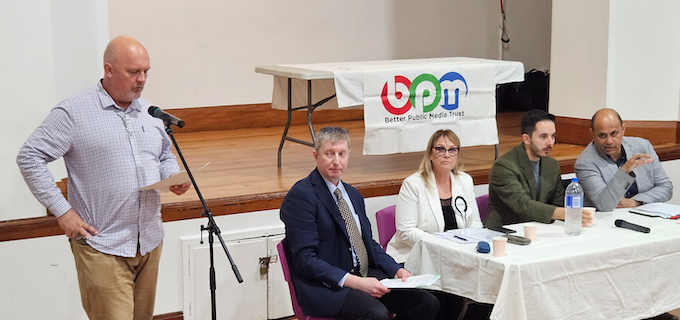

Myles Thomas is a trustee of the Better Public Media Trust (BPM). He is a former television producer and director who in 2012 established the Save TVNZ 7 campaign. Thomas is now studying law. This commentary was this year’s David Beatson Memorial Address at a public meeting in Grey Lynn last night on broadcast policy for the NZ election 2023.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz