Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Chris Hay, Professor of Drama, Flinders University

The 2024 intake into the Bachelors-level degree at the National Institute of Circus Arts (NICA) has been “paused”, reportedly on the grounds of financial viability and “strategic alignment” with Swinburne University, which has auspiced NICA since 1995.

In the same week across the Tasman, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington announced savage cuts to its theatre and music programs.

These are just the latest blows to a sector in crisis. They arise from a decades-long suspicion of the place of arts training in the academy, which can be traced back as far as the 1950s.

Then, arts training was seen as insufficiently rigorous and incompatible with university structures. Now, those same concerns are framed in terms of strategic value and return on investment.

Whatever the rationale, they speak to a lack of imagination and creativity in the administration of the contemporary university.An independent institution

At a meeting of its Professorial Board in December 1956, the University of Melbourne refused a proposal to establish a degree-level actor training program. The board declared the aims of the proposal could not “be fulfilled by a course which conformed to indispensable university standards”.

After this rejection, a similar proposal progressed at the University of New South Wales, with one critical difference.

While this actor training program would operate out of university facilities and be collocated with the School of English, it would remain separate.

George Pashuk © NIDA

The National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) was born in 1958. From its start, NIDA was physically integrated with but academically apart from its institutional sponsor.

Throughout its history and to today, to paraphrase long-time director John Clark, NIDA has revelled in its close association with the university – but closely guarded its independence.

Intellectual rigour

The suggestion in the late 1950s that the business of performer training was antithetical to the mission of the university was grounded in two related factors: matriculation standards, and the availability of suitably qualified staff.

Universities were sceptical of the intellectual rigour of artistic practice in the institution, both in prospective students and in staff.

Universities were also concerned about the lack of funding or teaching space for the higher intensity and longer hours demanded over more traditional tertiary subjects.

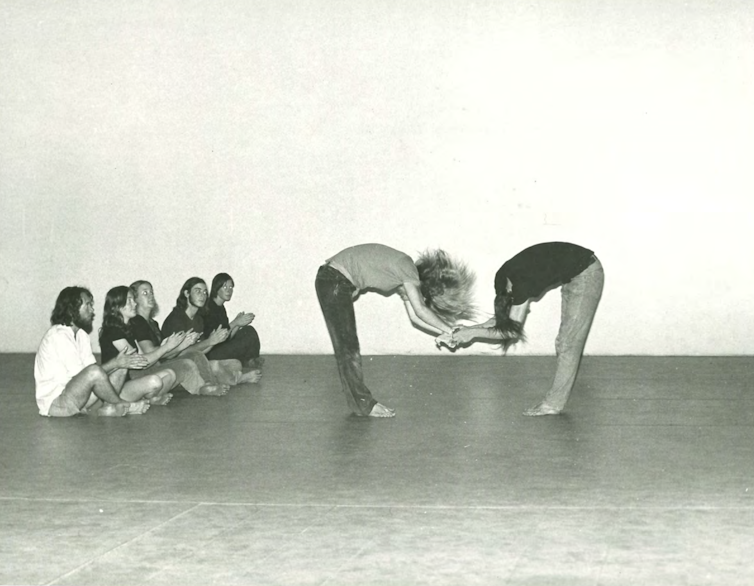

One exception stands out: the long-running actor training offered at Flinders University began in 1971, just five years after the university opened in 1966.

Flinders University

Otherwise, performers trained outside of university level institutions. Some joined the profession directly and trained on the job. Others were apprenticed through youth companies or student theatre, and graduated onto the professional stage.

Merging with the universities

In the intervening years, between 1967 to the early 1990s, much Australian arts training was housed within Colleges of Advanced Education (CAE). These colleges sat between TAFE institutions and universities, focusing on more vocational disciplines and awarding certificates, diplomas, and eventually degrees.

In the early 1990s, the Dawkins Reforms merged some technical and vocational providers with universities, and granted university status to others. This brought more arts training programs into universities.

WAAPA/ECU

The Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA), which had been housed within the Western Australian CAE since 1980, became part of Edith Cowan University.

The Kelvin Grove Campus of the Brisbane CAE, which had provided actor training since the late 1970s, was merged with the new Queensland University of Technology.

These new universities were beginning to articulate an academic identity. Their historical association with more vocational forms of training made them more open to maintaining the provision of arts training.

As part of this commitment, some institutions even founded new training programs. Swinburne established the National Institute of Circus Arts in 1995. The Griffith Film School followed in 2004.

By far the most contentious integration took place at the University of Melbourne in 2006, when the Victorian College of the Arts was first affiliated with and then fully integrated into the university.

Almost exactly 50 years after it was first rejected, actor training was now part of the business of that university – though not without a great deal of consternation and protest.

Various painful reorganisations followed, elegantly documented by Richard Murphet, as the university and the training institution worked through their differences – many the same as those identified by the Professorial Board in the 1950s.

Read more:

Friday essay: training a new generation of performers about intimacy, safety and creativity

The value of arts training

At its root, the uneasiness of the alliance between universities and performer training is a product of a perceived opposition between the intellectual and the manual.

This false binary discounts the ways in which knowledge is made by and held in the body, and the rigorous research-informed training cultures that have developed in university performing arts programs since the 1990s.

Too often, the universities themselves aren’t able to take on the very acts of imagination that characterise the training offered to students. Administrators instead see bloated programs that refuse to conform to increasingly rigid curriculum architectures.

Institutions that proclaim themselves to be innovative, agile and creative are increasingly unwilling to sustain the very programs that exemplify those qualities.

Budget bottom lines trump the values of the institution.

Far from being expensive follies incompatible with the institution, arts training programs act as the shopfront for the university. These programs intervene in civic life and showcase the university publicly. Their students activate campus spaces and bring community audiences to the university.

To maintain them does not require a commitment to the arts as an intrinsic good – though that would not go astray. It merely needs administrators to think differently, to make new models instead of insisting we fit the old, to imagine a better future.

Funnily enough, an arts training program could teach them precisely that.

Read more:

Friday essay: a world of pain – Australian theatre in crisis

![]()

Chris Hay receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

– ref. Intake to the National Institute of Circus Arts has been ‘paused’. Where to next for Australia’s performing arts training? – https://theconversation.com/intake-to-the-national-institute-of-circus-arts-has-been-paused-where-to-next-for-australias-performing-arts-training-209120