ANALYSIS: By David Robie

Two countries. A common border. Two hostage crises. But the responses of both Asia-Pacific nations have been like chalk and cheese.

On February 7, a militant cell of the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB), the armed wing of the Free Papua Organisation (OPM) — a fragmented organisation that been fighting for freedom for their Melanesian homeland from Indonesian rule for more than half a century — seized a Susi Air plane at the remote highlands airstrip of Paro, torched it and kidnapped the New Zealand pilot.

It was a desperate ploy by the rebels to attract attention to their struggle, ignored by the world, especially by their South Pacific near neighbours Australia and New Zealand.

Many critics deplore the hypocrisy of the region which reacts with concern over the Russian invasion and war against Ukraine a year ago at the weekend and also a perceived threat from China, while closing a blind eye to the plight of the West Papuans – the only actual war happening in the Pacific.

The rebels’ initial demand for releasing pilot Phillip Merhtens is for Australia and New Zealand to be a party to negotiations with Indonesia to “free Papua”.

But they also want the United Nations involved and they reject the “sham referendum” conducted with 1025 handpicked voters that endorsed Indonesian annexation in 1969.

Twelve days later, a group of armed men in the neighbouring country of Papua New Guinea seized a research party of four led by an Australian-based New Zealand archaeology professor Bryce Barker of the University of Southern Queensland (USQ) — along with three Papua New Guinean women, programme coordinator Cathy Alex, Jemina Haro and PhD student Teppsy Beni — as hostages in the Mount Bosavi mountains on the Southern Highlands-Hela provincial border.

The good news is that the professor, Haro and Beni have now been freed safely after a complex operation involving negotiations, a big security deployment involving both police and military, and with the backing of Australian and New Zealand officials. Programme coordinator Cathy Alex had been freed earlier on Wednesday.

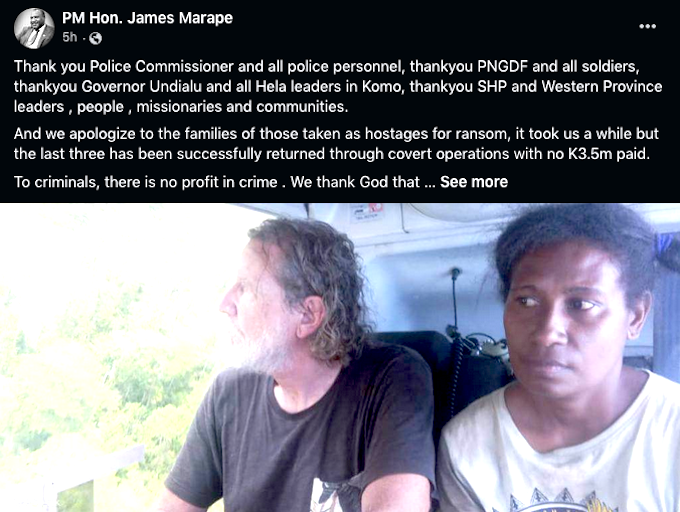

Prime Minister James Marape announced their release on his Facebook page, thanking Police Commissioner David Manning, the police force, military, leaders and community involved.

“We apologise to the families of those taken as hostages for ransom. It took us a while but the last three [captives] has [sic] been successfully returned through covert operations with no $K3.5m paid.

“To criminals, there is no profit in crime. We thank God that life was protected.”

Ransom demanded

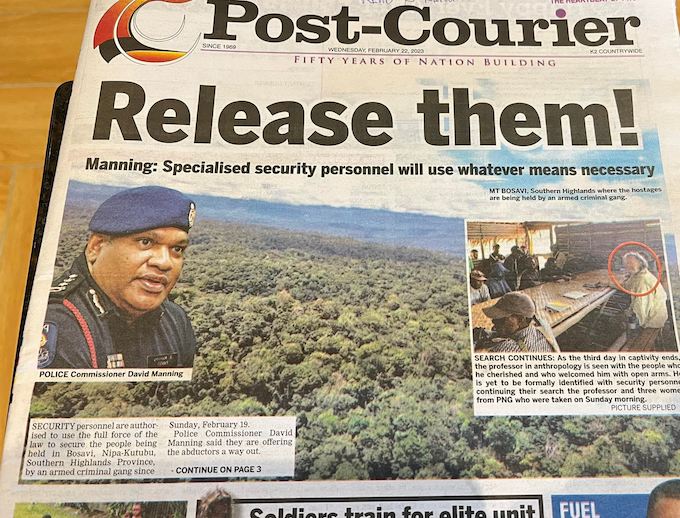

The kidnappers had demanded a ransom, as much as K3.5 million (NZ$1.6 million), according to one of PNG’s two daily newspapers, the Post-Courier, and Police Commissioner David Manning declared: “At the end of the day, we’re dealing with a criminal gang with no other established motive but greed.”

ABC News reports that it understood a ransom payment was discussed as part of the negotiations, although it was significantly smaller than the original amount demanded.

It was a coincidence that these hostage dramas were happening in Papua New Guinea and West Papua in the same time frame, but the contrast between how the Indonesian and PNG authorities have tackled the crises is salutary.

Jakarta was immediately poised to mount a special forces operation to “rescue” the 37-year-old pilot, which undoubtedly would have triggered a bloody outcome as happened in 1996 with another West Papuan hostage emergency at Mapenduma in the Highlands.

That year nine hostages were eventually freed, but two Indonesian students were killed in crossfire, and eight OPM guerrillas were killed and two captured. Six days earlier another rescue bid had ended in disaster when an Indonesian military helicopter crashed killing all five soldiers on board.

Reprisals were also taken against Papuan villagers suspected of assisting the rebels.

This month, only intervention by New Zealand diplomats, according to the ABC quoting Indonesian Security Minister Mahfud Mahmodin, prevented a bloody rescue bid by Indonesian special forces because they requested that there be no acts of violence to free its NZ citizen.

Mahmodin said Indonesian authorities would instead negotiate with the rebels to free the pilot. There is still hope that there will be a peaceful resolution, as in Papua New Guinea.

PNG sought negotiation

In the PNG hostage case, police and authorities had sought to de-escalate the crisis from the start and to negotiate the freedom of the hostages in the traditional “Melanesian way” with local villager go-betweens while buying time to set up their security operation.

The gang of between 13 and 21 armed men released one of the women researchers — Cathy Alex on Wednesday, reportedly to carry demands from the kidnappers.

But the Papua New Guinean police were under no illusions about the tough action needed if negotiation failed with the gang which had terrorised the region for some months.

While Commissioner Manning made it clear that police had a special operations unit ready in reserve to use “lethal force” if necessary, he warned the gunmen they “can release their captives and they will be treated fairly through the criminal justice system, but failure to comply and resisting arrest could cost these criminals their lives”.

Now after the release of the hostages Commissioner Manning says: “We still have some unfinished business and we hope to resolve that within a reasonable timeframe.”

Earlier in the week, while Prime Minister Marape was in Fiji for the Pacific Islands Forum “unity” summit, he appealed to the hostage takers to free their captives, saying the identities of 13 captors were known — and “you have no place to hide”.

Deputy Opposition Leader Douglas Tomuriesa flagged a wider problem in Papua New Guinea by highlighting the fact that warlords and armed bandits posed a threat to the country’s national security.

“Warlords and armed bandits are very dangerous and . . . must be destroyed,” he said. “Police and the military are simply outgunned and outnumbered.”

‘Open’ media in PNG

Another major difference between the Indonesian and Papua New Guinea responses to the hostage dramas was the relatively “open” news media and extensive coverage in Port Moresby while the reporting across the border was mostly in Jakarta media with the narrative carefully managed to minimise the “independence” issue and the demands of the freedom fighters.

Media coverage in Jayapura was limited but with local news groups such as Jubi TV making their reportage far more nuanced.

An Asia Pacific Report correspondent, Yamin Kogoya, has highlighted the pilot kidnapping from a West Papuan perspective and with background on the rebel leader Egianus Kogoya. (Note: Yamin’s last name represents the extended Kogoya clan across the Highlands – the largest clan group in West Papua, but it is not the immediate family of the rebel leader).

“There are those who regard Egianus Kogoya as a Papuan hero and there are those who view him as a criminal,” he wrote.

“It is essential that we understand how concepts of morality, justice, and peace function in a world where one group oppresses another.

“A good person is not necessarily right, and a person who is right is not necessarily good. A hero’s journey is often filled with betrayal, rejection, error, tragedy, and compassion.

“Whenever a figure such as Egianus Kogoya emerges, people tend to make moral judgments without necessarily understanding the larger story.

‘Heroic figures’

“And heroic figures themselves have their own notions of morality and virtue, which are not always accepted by societal moralities.”

He also points out that there are “no happy monks or saints, nor are there happy revolutionary leaders”.

“Patrice Émery Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, Malcom X, Ho Chi Minh, Marcus Garvey, Steve Biko, Arnold Aap and the many others are all deeply unfortunate on a human level.”

Last week, a riot in Wamena in the mountainous Highlands erupted over rumours about the abduction of a preschool child who was taken to a police station along with the alleged kidnapper. When protesters began throwing stones at the police station, Indonesian security forces shot dead nine people and wounded 14.

More than 200 extra security forces – military and police – were deployed to the Papuan town as part of a familiar story of repression and human rights violations, claimed by critics as part of a pattern of “genocide”.

West Papua breakthrough

Meanwhile, headlines over the pilot kidnapping and the Wamena riot have overshadowed a remarkable diplomatic breakthrough in Fiji by Benny Wenda, president of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), a group that is waging a peaceful and diplomatic struggle for self-determination and justice for Papuans.

Wenda met new Fiji Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka, the original 1987 coup leader, who was narrowly elected the country’s leader last December and is ushering in a host of more open policies after 16 years of authoritarian rule.

The West Papuan leader won a pledge from Rabuka that he would support the independence campaigners to become full members of the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), while also warning that they needed to be careful about “sovereignty issues”.

Under the FijiFirst government led by Voreqe Bainimarama, Fiji had been one of the countries that blocked the West Papuans in their previous bids in 2015 and 2019.

The MSG bloc includes Fiji, the FLNKS (Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front) representing New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, traditionally the strongest supporter of the Papuans.

Indonesia surprisingly became an associate member in 2015, a move that a former Vanuatu prime minister, Joe Natuman, has admitted was “a mistake”.

An elated Wenda, who had strongly distanced his peaceful diplomacy movement from the hostage crisis and appealed for the unconditional release of the pilot, declared after his meeting with Rabuka, “Melanesia is changing”.

However, many West Papuan supporters and commentators long for the day when Australia and New Zealand also shed their hypocrisy and step up to back self-determination for the Indonesian-ruled Melanesian region.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz