Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Rebecca Giblin, ARC Future Fellow; Associate Professor; Director, Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia, The University of Melbourne

Shutterstock

In 2020, the independent authors and small publishers whose audiobooks reach their readers via Audible’s ACX platform smelled a rat.

Audiobooks were booming, but sales of their own books – produced at great expense and well-reviewed – were plummeting.

Some of their royalty statements reported negative sales, as readers returned more books than they bought. This was hard to make sense of, because Audible only reported net sales, refusing to reveal the sales and refunds that made them up.

Perth-based writer Susan May wondered whether those returns might be the reason for her dwindling net sales. She pressed Audible to tell her how many of her sales were being negated by returns, but the company stonewalled.

Then, in October 2020, a glitch caused three weeks of returns data to be reported in a single day, and authors discovered that hundreds (and even thousands) of their sales had been wiped out by returns.

Suddenly, the scam came into focus: the Amazon-owned Audible had been offering an extraordinarily generous returns policy, encouraging subscribers to return books they’d had on their devices for months, even if they had listened to them the whole way through, even if they had loved them – no questions asked.

Encouraged by the policy, some subscribers had been treating the service like a library – returning books for fresh credits they could swap for new ones. Few would have realised that Audible clawed back the royalties from the book’s authors every time a book was returned.

Good for Amazon, bad for authors

It was good for Amazon – it helped Audible gain and hold onto subscribers – but bad for the authors and the performers who created the audiobooks, who barely got paid.

Understanding Amazon’s motivation helps us understand a phenomenon we call chokepoint capitalism, a modern plague on creative industries and many other industries too.

Orthodox economics tells us not to worry about corporations dominating markets because that will attract competitors, who will put things back in balance.

Read more:

Five ways to boost Australian writers’ earnings

But many of today’s big corporations and billionaire investors have perfected ways to make those supposedly-temporary advantages permanent.

Warren Buffett salivates over businesses with “wide, sustainable moats”. Peter Thiel scoffs that “competition is for losers”. Business schools teach students ways to lock in customers and suppliers and eliminate competition, so they can shake down the people who make what they supply and buy what they sell.

Locking in customers and creators

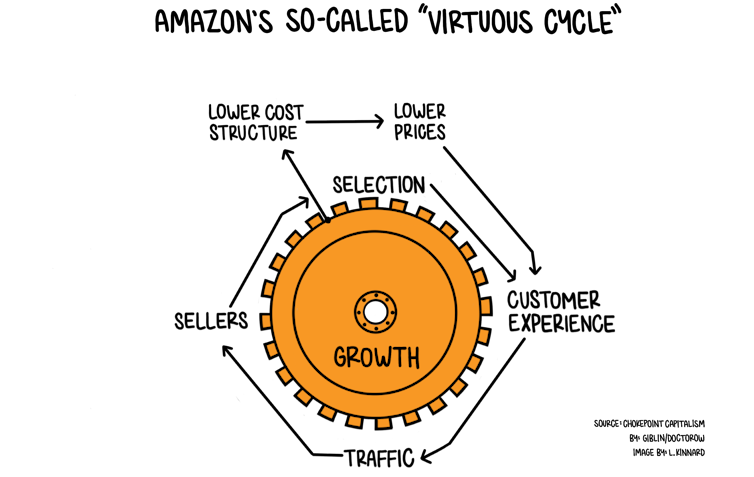

Amazon is the poster child for chokepoint capitalism. It boasts of its “flywheel” – a self-described “virtuous cycle” where its lower cost leads to lower prices and a better customer experience, which leads to more traffic, which leads to more sellers, and a better selection – which further propels the flywheel.

But the way the cycle works isn’t virtuous – it’s vicious and anti-competitive.

Amazon openly admits to doing everything it can to lock in its customers. That’s why Audible encourages book returns: its generous offer only applies to ongoing subscribers. Audible wants the money from monthly subscribers and wants the fact that they are subscribed to prevent them from shopping elsewhere.

Paying the people who actually made the product it sells a fair share of earnings isn’t Amazon’s priority. Because Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’ famous maxim is “your margin is my opportunity”, the executive who figured out how to make authors foot the bill for retaining subscribers probably got a bonus.

Another way Audible locks customers in is by ensuring the books it sells are protected by digital rights management (DRM) which means they are encrypted, and can only be read by software with the decryption key.

Amazon claims DRM stops listeners from stealing from creators by pirating their books. But tools to strip away those locks are freely available online, and it’s easy for readers who can’t or won’t pay for books to find illegal versions.

While DRM doesn’t prevent infringement, it does prevent competition.

Startups that want to challenge Audible’s dominance – including those that would pay fairly – have to persuade potential customers to give up their Audible titles or to inconveniently maintain separate libraries.

In this way, laws that were intended to protect against infringement of copyright have become tools to protect against infringement of corporate dominance.

Once customers are locked in, suppliers (authors and publishers) are locked in too. It’s incredibly difficult to reach audiobook buyers unless you’re on Audible. When the suppliers are locked in, they can be shaken down for an ever-greater share of what the buyers hand over.

How a few big buyers can control whole markets

The problem isn’t with middlemen as such: book shops, record labels, book and music publishers, agents and myriad others provide valuable services that help keep creative wheels turning.

The problem arises when these middlemen grow powerful enough to bend markets into hourglass shapes, with audiences at one end, masses of creators at the other, and themselves operating as a chokepoint in the middle.

Since everyone has to go through them, they’re able to control the terms on which creative goods and services are exchanged – and extract more than their fair share of value.

The corporations who create these chokepoints are trying to “monopsonise” their markets. “Monopsony” isn’t a pretty word, but it’s one we are going to have to get familiar with to understand why so many of us are feeling squeezed.

Monopoly (or near-monopoly) is where there is only one big seller, leaving buyers with few other places to turn. Monopsony is where there is only one big buyer, leaving sellers with few other places to turn.

In our book, we quote William Deresiewicz, a former professor of English at Yale University, who points out in his book The Death of the Artist that “if you can only sell your product to a single entity, it’s not your customer; it’s your boss”.

Increasingly, it is how the creative industries are structured. There’s Audible for audiobooks, Amazon for physical and digital versions, YouTube for video, Google and Facebook for online news advertising, the Big Three record labels (who own the big three music publishers) for recorded music, Spotify for streaming, Live Nation for live music and ticketing – and that’s just the start.

But as corporate concentration increases across the board, monopsony is becoming a problem for the rest of us. For a glimpse into what happens to labour markets when buyers become too powerful, just think about how monopsonistic supermarkets bully food manufacturers and farmers.

Scribe Publications

A fairer deal for consumers and creators

The good news is that we don’t have to put up with it.

Chokepoint Capitalism isn’t one of those “Chapter 11 books” – ten chapters about how terrible everything is, plus a conclusion with some vague suggestions about what can be done.

The whole second half is devoted to detailed proposals for widening these chokepoints out – such as transparency rights, among others.

Audible’s sly trick only finally came to light because of the glitch that let authors see the scope of returns.

That glitch enabled writers, led by Susan May, to organise a campaign that eventually forced Audible to reform some of its more egregious practices. But we need more light in dark corners.

And we need reforms to contract law to level the playing field in negotiations, interoperability rights to prevent lock-in to platforms, copyrights being better secured to creators rather than publishers, and minimum wages for creative work.

These and the other things we suggest would do much to empower artists and get them paid. And they would provide inspiration for the increasing rest of us who are supplying our goods or our labour to increasingly powerful corporations that can’t seem to keep their hands out of our pockets.

Chokepoint Capitalism: how big tech and big content captured creative labour markets, and how we’ll win them back is published on Tuesday November 15 by Scribe.

![]()

Rebecca Giblin receives funding from the Australian Research Council and state and territory libraries for the Author’s Interest Project (authorsinterest.org), the eLending Project (elendingproject.org) and Untapped: the Australian Literary Heritage Project (untapped.org.au). She is a Fellow of the CREATe research centre at the University of Glasgow, and a member of the Author’s Alliance and the Australian Digital Alliance. She has occasionally and intermittently used Audible’s service since its inception (though has not been a subscriber for a very long time),buys goods and services from Amazon when she really has to, subscribes to Spotify (where she sometimes listens to music controlled by the Big Three record labels, and published by their Big Three music publisher subsidiaries), and sometimes watches videos on YouTube.

Cory Doctorow is a consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. He co-founded the UK Open Rights Group. He is a visiting professor of practice at the University of North Carolina’s School of Library and Information Science. He is a dues-paying member of the Free Software Foundation and FSF Europe. His books and audiobooks are published by Random House, Macmillan, Beacon Press, McSweeney’s, HarperCollins, Hachette, and many other publishers. These are for sale on Amazon, Excerpts of his work are for sale on Audible. He runs a personal ebook store (craphound.com/shop) that compete with Amazon and Audible for ebook and audiobook sales. One of his books was favorably reviewed and endorsed by Jeff Bezos.

– ref. Chokepoint Capitalism: why we’ll all lose unless we stop Amazon, Spotify and other platforms squeezing cash from creators – https://theconversation.com/chokepoint-capitalism-why-well-all-lose-unless-we-stop-amazon-spotify-and-other-platforms-squeezing-cash-from-creators-194069