Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Stephen Duckett, Honorary Enterprise Professor, School of Population and Global Health, and Department of General Practice, The University of Melbourne

Medicare, Australia’s universal health insurance scheme, provides financial protection against the cost of medical bills, and makes public hospital care available without any charge to the patient. For the large majority of Australians in urban settings, it is a brilliant system – providing subsidised access to care.

But subsidised access is only useful for those who have access. If there is no doctor nearby, there is nothing to subsidise. This creates a huge inequity – most of Australia has good access to doctors, but the Northern Territory does not.

And what’s worse, there is no effective policy to redress the inequity that payments flow to areas where there are doctors.

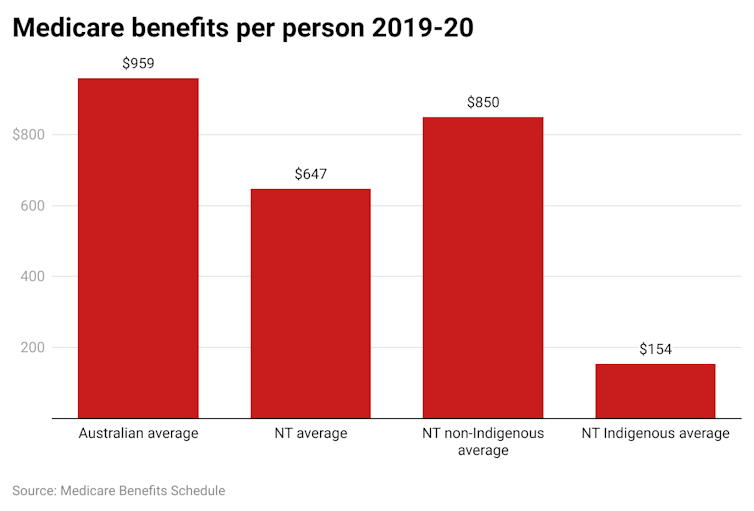

In our recently published paper, we found NT residents receive roughly 30% less Medicare funding per capita than the national average (A$648 compared with A$969).

The gap is worse for First Nations Australians in the NT, who attract only 16% of the Medicare funding of the average Australian.

Read more:

Labor’s health package won’t ‘strengthen’ Medicare unless it includes these 3 things

We measured the extent of the problem over the years 2010–20. We used the federal government’s published figures on Medicare to explore the impact of this uneven workforce distribution on Medicare billing in the NT.

The differences are stark.

The inequitable funding is even worse when the poorer health status of First Nations Australians and the additional costs associated with geographical remoteness are taken into account.

The NT has a younger age profile than the rest of Australia, but this explains only one-third of the gap.

What’s going wrong with the funding?

Despite Medicare’s intended universality, the NT is systematically disadvantaged.

People in the Territory have poorer access to primary health care, which includes GP services and those provided by Aboriginal community-controlled health services.

Aboriginal health services receive some special additional funding separate from the Medicare-billing funding. However, even with that extra funding, there is still a shortfall to NT residents of about A$80 million each year.

The NT government receives a relatively higher proportion of the GST funding pool in recognition of its challenges with remoteness and Indigenous services. But this is calculated assuming NT residents have the same access to Medicare as all other Australians. As we have shown, they don’t and so the extra GST funding does not result in a fair funding stream to meet NT primary care needs.

The outcome of inadequate primary health care funding is increasing reliance on hospital services. People’s chronic health conditions worsen if they’re not well managed in the community and this increases the risk they will need a hospital admission, especially for “potentially preventable hospitalisations”. NT hospitals experience excessive pressure of workload and complexity as a result.

Shutterstock

We have shown previously that effective primary health care for remote patients with chronic, long-term diseases can substantially reduce their use of hospital services and result in better health outcomes at a lower cost.

When visiting the NT in 2000, one of the architects of Medicare, John Deeble, observed the funding failure first hand and suggested another form of health-care financing was needed to adequately support remote primary health care.

In terms of health equity and our national commitment to close the life expectancy gap for First Nations peoples, the status quo is undeniably short-changing our efforts.

What needs to be done?

There needs to be a reset in how we finance remote primary health care services in the NT.

The value proposition is excellent. Due to the extreme health needs and vulnerable populations, the return on investment is high – more than A$5 in saved acute care costs for every dollar invested.

The federal government’s Health Care Homes funding reform trial was very successful in remote NT communities. For the first time, service providers received flexible funding to care for patients’ chronic conditions, rather than a fee for each service they provided. It also enabled the provider and patient to develop a relationship.

Unfortunately the Health Care Homes program ended in June 2021, and has not been renewed. This program should be reinvigorated for chronic disease care in the NT and extended to include other core programs of mental health and suicide prevention, and child and maternal health.

The federal government should take this opportunity to get remote primary health care financing right and ensure Medicare funds reach those who need them most.

Read more:

How do the major parties rate on Medicare? We asked 5 experts

Acknowledgement: Xiaohua Zhang, Jo Wright, and Maja Van Bruggen from the Northern Territory Department of Health are co-authors of the journal article on which this article is based.

![]()

John Wakerman receives funding from The Australian Research Council, the Medical Research Future Fund and the NT Primary Health Network.

Paul Burgess has previously received grant funding as an investigator on MRFF, NHMRC and the Digital Health CRC funded projects. No funding was received for the work that led to this publication. Paul works for the NT Government.

Rus Nasir worked for the NT Government as acting director of Aboriginal health.

Yuejen Zhao works for the NT Govnernment.

Stephen Duckett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. First Nations people in the NT receive just 16% of the Medicare funding of an average Australian – https://theconversation.com/first-nations-people-in-the-nt-receive-just-16-of-the-medicare-funding-of-an-average-australian-183210