Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Janet McCalman AC, Emeritus Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor, The University of Melbourne

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

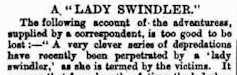

“A LADY SWINDLER”, gasped the Illustrated Australian News in November 1867.

It appears that for a length of time the lady has been in the habit of visiting lodging houses and inquiring for apartments […] Having agreed to take the lodgings she proceeds to pay a deposit, when, lo! on feeling in her pocket, she cries, ‘I’ve lost my purse; they have stolen my purse,’ and forthwith commences to lament and bemoan her loss, exclaiming, ‘What shall I do; what will my husband say’.

The lady is always accompanied by a little boy, dressed in Highland costume, whose tears mingled with sobs of his mother, are the secret of the facility with which she accomplishes her schemes.

The lady swindler was Mrs Alexandrina Askew. She didn’t ask for money, loans were offered in her time of crisis. As she collected more funds, her clothes became more ladylike.

Outside Melbourne she would suddenly appear from the bush and de-materialise back into it afterwards. Throughout all her forays, she insisted her husband was a wealthy squatter near Piggoreet with 30,000 sheep and 900 head of cattle.

One conquest in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond involved the family of a coach-maker, one of whose buggies she fancied buying. They invited her to take sherry and conversation flowed: about the squatter husband, the home property.

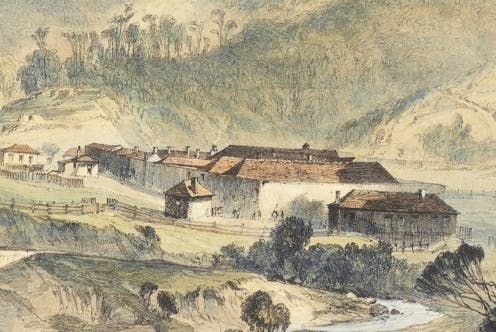

Author provided

Mrs Askew took particular interest in the daughter of the family, who was feeling poorly and in need of country air, prompting her to invite the daughter to travel with her to Piggoreet and stay awhile to recover her health. Such a pity it was that the new friends should miss each other the next day at Spencer Street Station.

Read more:

Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

An imaginary family

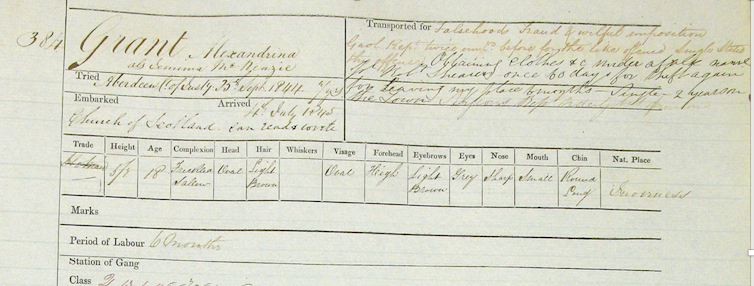

Alexandrina, or Jemima or Alice, as she became in later life, arrived as Alexandrina Grant on the convict ship Tory in Hobart in 1845, along with 30 other Scottish women among a shipload of 170, otherwise from England.

She was 18, allegedly born in Inverness, and had been transported for “falsehoods, fraud and wilful imposition” in obtaining clothes.

Like all convicts transported by the Scottish courts, she had form. She had been convicted in Aberdeen at the age of 17 and had already served 60 days for theft, she reported also that she had done six months for “leaving my place” (that is, leaving her position as a servant while under contract).

When she alighted in Hobart, she recited an imaginary family to the convict clerk: her father John and her brothers William, James, Dennis, Alexander, John and Donald, plus her sister Elizabeth, all in Scotland.

Author provided

But there is no sign of them in the census: there is no record of a Dennis Grant anywhere in Scotland before 1901. She was, in fact, a bastard child born in gaol to convict parents.

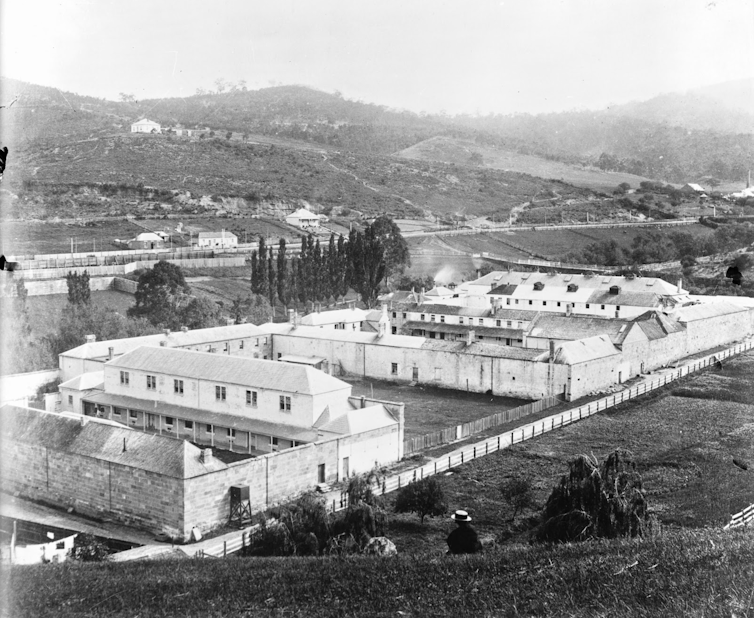

On the voyage out, the perceptive ship’s surgeon described Alexandrina as “orderly but precious”. Under her seven-year sentence she was frequently absent without leave, meeting men at night, and consequently bore an illegitimate child in Hobart’s Cascades Female Factory in 1849.

She found no-one presumably good enough to marry her, and domestic service was not to her liking (she was twice dismissed from her places of assigned service), so she spent most of her sentence in the female factories where women were punished and put to work doing tasks such as laundry “at the tubs”.

Social dysphoria

Alexandrina’s story illustrates in extreme personal form the pain of perceived inferiority and stigma felt by those transported to Van Diemen’s Land: the daily humiliations of being a nobody, without a family let alone a lineage. If her secrets and lies were spectacular, they were nonetheless reflective of the desperation of the socially thwarted and ignored.

She felt she deserved to be a somebody, a woman of refinement, respected and deferred to – not an old lag, a former homeless woman of the town. She suffered a form of social dysphoria, born into the wrong social body. Alexandrina knew how to speak and deport herself like a lady, except her secret was that she wasn’t.

Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office

The terrible daily burden of the convict stain – of spoiled identity – meant people had to lie and withhold secrets, even from their own partners and children.

There were significant passages of their lives that could not be spoken of, stories that could not be recounted, memories that could not be shared. Always they had to calculate how best to obscure the missing seven or ten years of their servitude in their personal narrative.

Many changed their name and then had to guard against dropping the wrong name, or place of birth, or work history, let alone criminal history. Many, it seems, succeeded admirably in concealing their convict past from their families, only to be found out later by assiduous genealogists.

Vandemonians were expected to re-enter society at the bottom of the human ladder and remain there. Over time they might be tolerated as amusing eccentrics, or shunned as people of untrustworthy character, but either way they could not rise and blend in with those who had been received. They had crossed over to “the other side”, and there they were doomed to remain.

But among the convicts of Van Diemen’s Land was a clutch of women whose crimes were yearnings for things above their station: for positions, husbands, lodgings, or finery or jewellery they could not pay for. They had the good fortune to be born good-looking and intelligent and so they could be plausible and ladylike. Alexandrina was tall and attractive and spoke well.

They were also especially vulnerable to seduction and abandonment, and the trigger for crime was often a betrayal or desertion by a lover.

A success story

Why is this story worth telling beyond its poignancy? It matters because Alexandrina Grant was a success among Scottish convict women transported to Van Diemen’s Land.

She lived into her ninth decade; was not a conspicuous drunkard; and married a free man, William Askew, who stayed with her. They went to the gold mines at Bulldog (now Bullarook) near Piggoreet. Her swindling career forced them to relocate to Ballarat, then Echuca and finally, Sydney.

She bore ten children, six of whom lived into middle life; and successfully delivered and reared the illegitimate child of her second daughter under the common fiction that the child was her own.

Moreover, two of her daughters, including the one who had a baby out of wedlock at 16, married good providers, even if one was an eccentric Swiss-Italian, self-styled professor who dealt over the years variously in mesmerism, phrenology, homeopathy and marriage guidance.

Alexandrina, who died in 1913, was apparently loved. The final chapter of her life took place in Sydney, where she ran boarding houses at dubious addresses in Redfern, twice going bankrupt. Few of the 1636 Scottish women transported to Van Diemen’s Land achieved anything like this ordinary triumph over poverty, stigma and marginalisation.

Janet McCalman’s book Vandemonians is out now (MUP).

![]()

Janet McCalman AC receives funding from the Australian Research Council

– ref. Hidden women of history: how ‘lady swindler’ Alexandrina Askew triumphed over the convict stain – https://theconversation.com/hidden-women-of-history-how-lady-swindler-alexandrina-askew-triumphed-over-the-convict-stain-169023