Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Nicole Moore, Professor of English, UNSW

Any social movement needs inspiration. It needs people who can imagine a different future and, more than that, make that future graspable.

Kate Jennings did that for the Australian women’s movement — with her incandescent anger, her sharp tongue and her courage, ready and able to speak straight into the face of power. Her death, in New York aged 72, offers a moment to reflect on the role of writers and literature as forces of social transformation.

When Jennings lined up for her turn to speak at a Vietnam moratorium rally on the lawns of Sydney University in 1970, she was a half-drop-out from Sydney’s English Department, living in Glebe.many women are beginning to feel the necessity to speak for themselves, for their sisters.

i feel that necessity now.

With the group of determined women libbers at her back, she perhaps wasn’t clear what her speech would do — that it would effectively inaugurate second-wave feminism in Australia and help it become a movement with its own momentum. A new chapter for the world’s longest revolution. But she did know that the time had come.

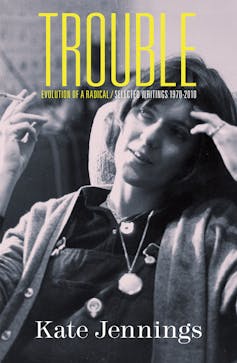

When the speech appeared as a performative poem in her 2010 retrospective collection Trouble: Evolution of a Radical, she recalled that the group had conceived it as deliberately incendiary.

“Call the speech what you like — agitprop, political theatre, over the top, in your face — but we were genuinely angry, famously fed up. I wrote the speech at a boil: we were getting nowhere asking the men in the movement to listen to us.”

Written from within the mix of galvanising struggles then being fought around the world, the speech tore shreds off those for whom women’s issues were secondary or trivial. She compared the number of Australian men who’d died in Vietnam with the number of women who’d died from illegal abortions.

It was a shocking thing to do then: a similar comparison, now, of the victims of domestic violence to the number of Australian soldiers lost to recent conflicts or suicide, would be met with outrage too. The speech was hardline, uncompromising, militant.

okay i’ve stopped trying to understand my oppressor

i know who my enemy is

i will tell you what i feel, as an individual, as a woman

i feel that there can be no love between men and women

And that passion came from poetry. It wasn’t the theorists or social commentators who inspired the radical feminism powering the speech, she recalled, but the eloquence of visionaries.

In 2010, she listed Robin Morgan, Ti-Grace Atkinson, Valerie Solanas’s SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto as her touchstones. This was writing that was “unafraid to be emotional, luminous with rage,” she recalled. “Manifestos and poems that jumped off the page. I loved it.”

Mother I’m Rooted

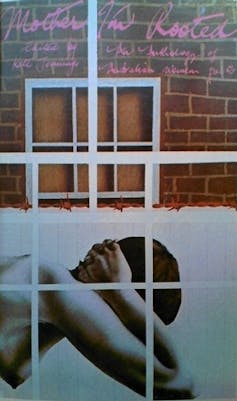

Jennings’ other extraordinary contribution to the transformational feminism of the 1970s is one of its most revelatory — the huge, collaborative women’s poetry collection called Mother I’m Rooted, published in 1975.

Its confronting title is a distillation of the protest and exhaustion she saw in the poems. With Alison Lyssa, another poet and activist, she planned an anthology as inclusive as possible and advertised for poems — “trying to reach the women Out There”. Within two months they had over 500 replies.

The final volume lists 152 poets, including established ones, unknowns with new feminist pseudonyms, seasoned activists from the old left and many names that would go on to make their marks. It has experimental, Greek-Australian writers contesting the definition of poetry and forthright, white, working-class women writing about the washing — though no First Nations poetry.

It is a beautiful social document now, broken up by lambent photographs of ordinary women together. And its call for women’s control over not just what counted as poetry but over the publishing process itself was hugely influential, arguably changing the literary landscape in Australia forever.

Fierce honesty

Across her writing life, Jennings produced essays, novels, short stories and journalism, as well as poetry, all written with a fierce honesty and wit, refusing what she saw as cant and sentiment.

After she moved to New York in 1979, she continued to write about and for Australia, but often with an outsider’s cynicism. Women Falling Down in the Street, a collection of short stories from 1990, won a Queensland Premier’s Literary Prize and perhaps typified her interest in revisionary engagement with her part in Australia’s cultural life.

The novel Snake, from 1994, explored with concision and power her country childhood on a farm outside Griffith in NSW, and found an international readership.

In 2002, after her husband’s death from Alzheimer’s disease, she published Moral Hazard, a short but perfectly voiced novel about a writer making a living on Wall Street to support a dying partner. One of the few Australian novels to confront the operations of capital directly, even pre-empting the 2008 global collapse, it won a number of prizes, including the ALS Gold Medal.

The legacy she leaves is complex and multi-voiced, marked often by a reassessment of her younger self by the older Jennings and, perhaps, by a certain distrust of any shared story she couldn’t control.

But that legacy has been transformative and extraordinary, by any measure.

– ref. ‘Famously fed up’. How the work of feminist writer Kate Jennings changed Australia – https://theconversation.com/famously-fed-up-how-the-work-of-feminist-writer-kate-jennings-changed-australia-160267