Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Kwadwo Adusei-Asante, Senior Lecturer, Edith Cowan University

Review: Black Brass, written and performed by Mararo Wangai; directed by Matt Edgerton. Performing Lines WA for Perth Festival.

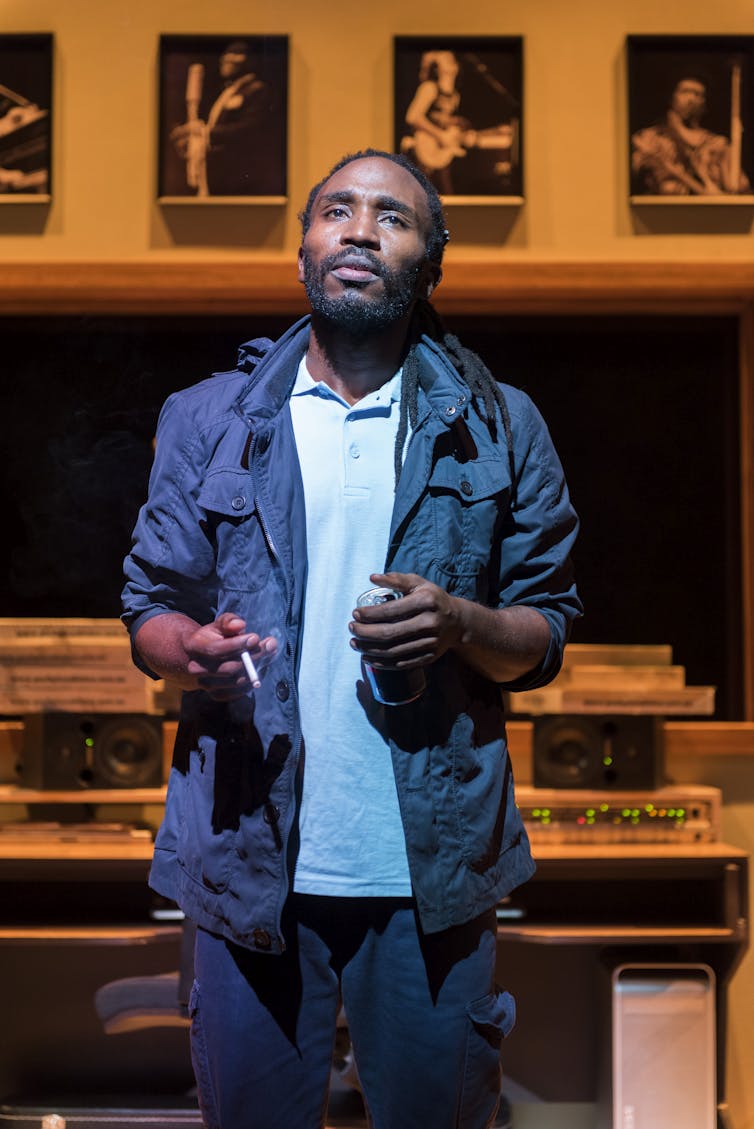

The scene opens into a messy music studio, used bottles and pizza boxes littered everywhere. A young man of sub-Saharan African descent appears, exhausted, entering the room late at night.

As the young janitor starts cleaning, he is distracted by the music playing in the background. Suddenly, the security alarm goes off: he has forgotten the code and immediately calls his manager to request assistance.

Over the phone, we hear his manager reprimand him, but he sounds more interested in petting his dog than providing the code and protecting the welfare of the cleaner.

Black Brass is a captivating theatrical piece written and performed by Mararo Wangai as the janitor named Sleeper, and accompanied by musician Mahamudo Selimaneat. The show is well executed in all areas: the oratory prowess of Wangai as Sleeper, the transitions, lighting, music and innovative rotating stage were superb.But behind the artistic brilliance, Black Brass is a story of the harsh realities faced by many African-Australians.

Hyphenated identities

Black Brass is the story of people with hyphenated identities: the Black Africans who juggle and struggle with who they are.

They live here, they were schooled here, they work here, they are “Australians” — but feel they don’t belong here, in a country that constantly asks “where are you really from?”

Australia’s Immigration Restriction Act 1901 ushered in the White Australia Policy, prohibiting the permanent settlement of Asians, Black Africans and other coloured races in the country.

The abolition of this racist policy in the 1970s by the Whitlam government opened the doors for non-white, non-European immigrants, but neo-White Australian Policies — such as citizenship tests — are still with us, effectively determining who comes to Australia and who does not.

Only 5.1% of Australia’s population were born in sub-Saharan Africa (including White Africans). Clearly, not many Black Africans live in Australia — but, as portrayed in Black Brass, many Black Africans who live here have many troubles.

Blackness in Australia is too often seen as not only inferior, but burdensome. Still, when Wangai interviewed people from Perth’s Zimbabwean, Sudanese, South African, Central Congo, Mauritius, Nigerian, Congolese and Kenyan communities to develop his script, he focused on the theme of resilience.

Brilliance

As Sleeper finally gets his boss to provide the code, we hear police sirens. Sleeper would be all too familiar with police brutality against black bodies and operations that target Black Africans.

The play shows how he subconsciously begins to plan for his arrest and a defence against potential incarceration — or even being shot dead (though he is unarmed).

Then, Sleeper sighs with relief. The police are not coming to where he is, after all: a white-man’s music studio late at night.

Sleeper laments his underemployment in the country he now calls home. He doesn’t like his job, it demeans him; but he needs to make ends meet for himself and his extended family in Africa, who depend on him financially.

This is the resilience of the Black African. Sleeper’s extraordinary retentive memory and excellent command over the English language are a testament to his brilliance.

Sleeper lives in a country where skin colour matters more than what a person can offer. It’s a country that so often reduces Black Africans who hold masters and doctoral qualifications earned in Australia to taxi drivers, cleaners, security wardens and menial job workers.

Not all Black Africans are underemployed in Australia, but sadly many gainfully employed Black Africans pay the “black tax”: an unspoken requirement to do more to keep their jobs, or move up the corporate ladder, than their non-black colleagues.

Read more: A degree doesn’t count for South Sudanese job seekers

Highly qualified Africans in Australia remain underemployed. Perhaps, suggests Black Brass, bosses are more interested in their pets.

The other reality of this performance is that Sleeper misses Africa. He misses his parents and family. He misses his fiancée, who has stayed in Africa when her visa for Australia was refused. Part of him would like to go back to where he came from and start afresh. But it is not a simple decision.

The corruption, the abuse of power by the political elite, the lack of opportunities in his home country scare Sleeper. He feels trapped in a world where almost everyone — including blacks — hate blacks.

But, on stage, he finds solace in the soulful music of Mahamudo. Although their colonial past has eroded their ability to communicate in the same language, they find a common ground in African music.

Meanwhile, Sleeper has to keep cleaning up the mess in the white man’s studio. We don’t know this job will ever end.

– ref. ‘Where are you really from?’ The harsh realities of Afro-Aussie life are brought to stage in Black Brass – https://theconversation.com/where-are-you-really-from-the-harsh-realities-of-afro-aussie-life-are-brought-to-stage-in-black-brass-156110