Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Catherine Speck, Professorial Fellow (Honorary), The University of Melbourne

Review: Clarice Beckett — The Present Moment, Art Gallery of South Australia

Featuring the artist’s luscious and distinctive soft focus, the Art Gallery of South Australia’s newly opened Clarice Beckett exhibition, curated by Tracey Lock, presents her paintings as a sensorium — with colour, music and video to enhance the experience.

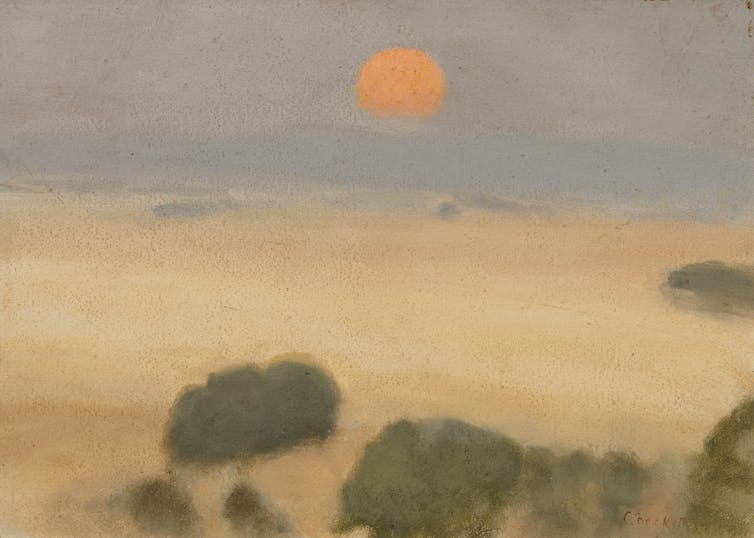

Each room in the gallery’s exhibition space is dedicated to her paintings of specific times of the day, from sunrise, to early morning, then midday and sunset, concluding with the nocturnes. She was fascinated with temporal change. The exhibition is very much an experiential journey. Viewers enter through an elliptical portal to an immersive rounded space filled with magnified projections of her paintings, and music from Simone Slattery’s specially commissioned soundscape.

Beckett was musical too. The transcendence to another realm has begun. The mood changes with each room in the exhibition.

A sad loss but precious works remain

The poignant Clarice Beckett story is known by many. She died from pneumonia in 1935 at 48 years of age, and left behind a large cache of work. It was stored for a number of years in an open-side shed in rural Victoria, only to be discovered in the late 1960s, in a poor state of repair, by art historian Rosalind Hollinrake. She salvaged a mere 369 paintings — 1,600 were beyond repair.Hollinrake guided the artist’s rediscovery at a time when numerous women artists were reinserted into the canon. The impetus for this exhibition is the generous donation by Alastair Hunter of a large collection of Beckett’s work previously held by Hollinrake.

Beckett lived in Beaumaris from 1919 with her ageing parents, and she was a familiar figure painting en plein air, meaning: in the open air.

The artist would walk miles to nearby beaches or districts to paint, fascinated with observing and portraying the changing mood and movement of the day. She was known to rise at 4am and walk to a nearby beach to watch the dawn rise as portrayed in Silent approach (circa 1924), in which shapes are just beginning to emerge with the coming morning light. Minimal figuration leaves painterly space for contemplation of a higher realm.

Read more: How our art museums finally opened their eyes to Australian women artists

Mysticism meets science

Theosophy — a belief in divine wisdom via mysticism — was a major influence on her approach to painting. Like others around the world, Beckett came under the popular esoteric movement’s spell in the early years of the 20th century. She owned a well-thumbed copy of Madame Blavatsky’s seminal occult text The Voice of Silence, attended spiritualist meetings and moved in artistic circles where post-dinner seances were often held.

But Beckett also took on board painter Max Meldrum’s quasi-scientific ideas about rational analytic observation of subtle visual patterns of tones and accents. She studied with him for nine months, although it is widely accepted she surpassed him with her brilliant tonal landscapes. This is the hybrid intellectual and artistic milieu she moved in, supplemented by an interest in Eastern philosophy and Freud.

For Beckett, painting was as much about performing her spiritual beliefs as it was about portraying that which was observable. Her friends in the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors, to which she belonged, recall she loved talking about theories behind her work.

What emerges in the exhibition is her finely honed and daring visual language. In some a compositional tension emerges between horizontal and vertical forms as in Wet night, Brighton (1930). That tension marks a point of transcendence.

Read more: Friday essay: the Melbourne bookshop that ignited Australian modernism

In others her economy and discipline in imagery is awe-inspiring as in Passing trams (circa 1931), in which the mist enveloping the trams is relieved by the merest gesture of colour; while her sheer versatility as an artist emerges in her busy yet spacious beach scenes in full sun, Sandringham Beach (circa 1933) and Sunny morning (1933).

In magical paintings such as Across the Yarra (circa 1931), a study in transience, the moonlight bleeds through the hazy evening mist and merges with glimmering lights reflected from the city onto the river. Its filtered grey light, close tonal range and soft edges prompt contemplation of a higher plane. In yet another painting the day’s heat coming off the surface of the land is palpable in Summer fields (1926), seen at sunset.

An artist without a studio

A curatorial coup is achieved with the installation of a domestic kitchen in the exhibition space. Her father had declined her request for a studio to work in. He suggested she use the kitchen table instead.

While most of her paintings were completed outdoors, she did paint still life and portraits, and finish off larger en plein air works at home. This work was indeed done on the kitchen table, which is so tellingly included in the exhibition, surrounded by her still life paintings including Marigolds (1925).

Read more: Why weren’t there any great women artists? In gratitude to Linda Nochlin

The exhibition ends on a high note with “the shed”. Artist Peter Drew’s filmic time-lapse sequence of a shed, any shed, is emblematic of the Clarice Beckett legend. It is symbolic of the fragility of one’s archive, and a memorial to Beckett whose legacy was almost lost.

Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment is an immersive curatorial gesture which takes viewers through the cycles of the day she portrayed. More than that, it causes viewers to stop, contemplate each painting, to experience the void, and to enter another realm.

Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment is on show at the Art Gallery of South Australia until May 16 2021.

– ref. Clarice Beckett exhibition is a sensory appreciation of her magical moments in time – https://theconversation.com/clarice-beckett-exhibition-is-a-sensory-appreciation-of-her-magical-moments-in-time-153720