Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By William Peterson, Adjunct Associate Professor, Auckland University of Technology

Between COVID, increasing production and transport costs, and changing audience tastes, the country’s largest arts festivals have had to rebadge themselves.

Festivals in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Perth have all undergone major cultural shifts – generally away from internationalism. The new kid on the block, Hobart’s Dark Mofo, offered a brew of Tasmanian winter funkiness. This vision was transferred to Melbourne’s Rising Festival in the wake of lockdowns.

This leaves the Adelaide Festival, founded in 1960, as the venerable grandparent of the region’s art festivals. Against the odds, the Adelaide Festival continues to offer a carefully curated program of international work, placing it in active conversation with domestically produced work.

From 2017-2023, festival co-directors Neil Armfield and Rachel Healy delivered a solid program that balanced high-culture spectacle with local work. Their curatorial choices required mutual approval, extensive travel to international festivals, and healthy doses of fortitude.

This year’s was the first full program curated by experienced international festival director Ruth Mackenzie, who has worked extensively in the UK and Europe. Under her watch, the festival placed high-quality Indigenous Australian work front and centre, while also showcasing superb offerings from the nation’s smaller companies.

On the international front, it brought big-ticket extravaganzas alongside outstanding theatre and dance groups from outside the mainstream.

I saw all the shows in this year’s theatre, music theatre, dance, dance theatre and opera categories. The music and visual arts program, as well as the events of Writer’s Week and WomAdelaide, were too much to take in simultaneously.

Indigenous Australia front and centre

When it comes to programming Indigenous work in the festival, pulling existing work off-the-shelf isn’t possible. And if it were, it wouldn’t be respectful or desirable.

Daniel Boud

Indigenous artists must be in positions of cultural and artistic leadership. Perhaps the greatest challenge is identifying and obtaining the financial resources from local and national funding bodies to support these artists.

Such work requires tact, solid community contacts and a deep knowledge of how funding and local systems work. Mackenzie, with the help of chief executive Kath M. Mainland and a capable festival staff, appears to have mastered these challenges.

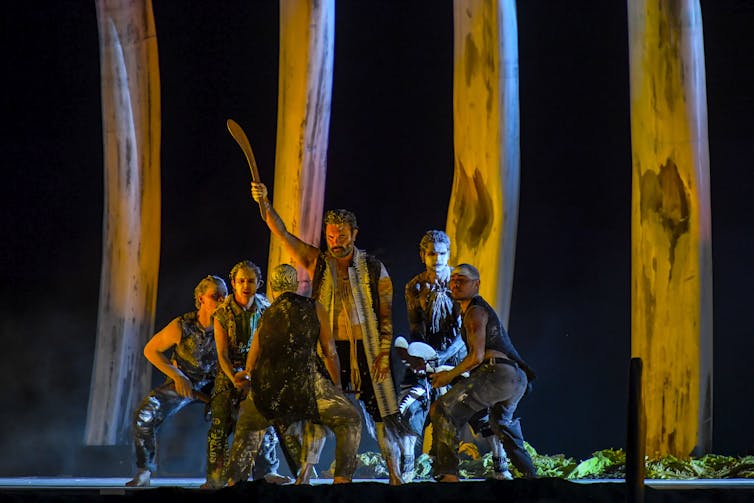

This year’s festival featured outstanding works by Indigenous artists both local and national. For me, the standout was Baleen Moondjan, Stephen Page’s first commissioned work since leaving the helm of the Bangarra Dance Theatre.

SA UAVs

Staged on a sandy ridge amid a row of whale bones extending to the water’s edge at Glenelg (Pathawilyangga) Beach, the work dramatised the transfer of faith, spirit and knowledge across the generations.

Masterfully blending music, dance, movement, song and text, it featured powerful performances from Elaine Crombie as Moondjan elder Gindara, and Zipporah Corser-Anu as her granddaughter.

Roy VanDerVegt

Guuranda, written and directed by Jacob Boehme, was another breakthrough work of local Indigenous storytelling. Like Baleen Moondjan, it was commissioned by the festival and supported by donors to the Adelaide Festival First Nations Commissioning Program.

The creative team drew from consultations with four elders from Narungga Country, traditional owners of the Yorke Peninsula region. Their personal stories were connected to creation stories linked to physical features of the land.

These ancient, living stories were beautifully evoked through dance and song. Lyrics in Narungga, written by Jacob Boehme and Sonya Rankine, were powerfully delivered by Rankine, Warren Milera and the Narungga Family Choir.

Tim Standing

Another standout was the Australian Dance Theatre’s production of Marrow, choreographed by Daniel Riley.

The starting point for this work, Riley noted in post-show remarks, was the heartbreak that followed the failure of the Indigenous Voice referendum in October.

This work evoked that disappointment viscerally. Dancers moved with difficulty, against obstacles, then walked backwards toward the audience. Later they were tossed about, as if responding to external blows.

The work’s trajectory suggested it is the power of the land itself that provides the strength to continue the fight.

A celebration of indie creators

Australian work has long had a strong presence in the festival. But this year’s programming brought festival audiences into unaccustomed spaces to experience work by some of the nation’s most consistently interesting non-mainstream companies.

No longer was the best work of our independent companies relegated almost exclusively to the nation’s two large Fringe festivals (Adelaide and Melbourne). Mackenzie had the curatorial confidence to program their work alongside audacious, high-brow, big-ticket extravaganzas from some of the world’s most famed directors and choreographers.

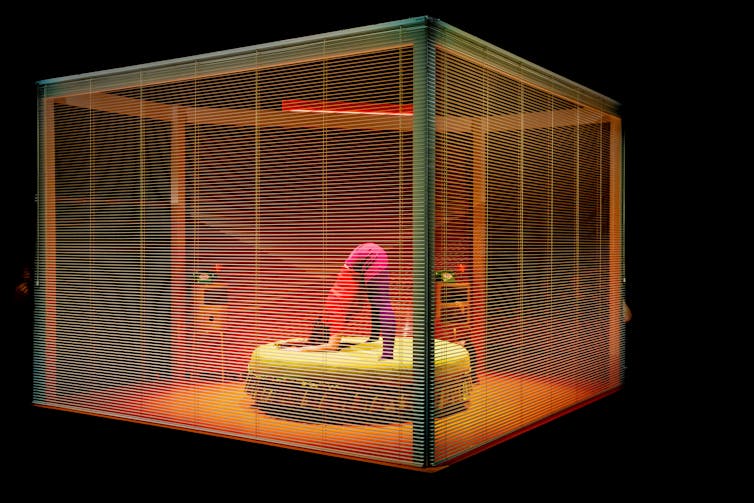

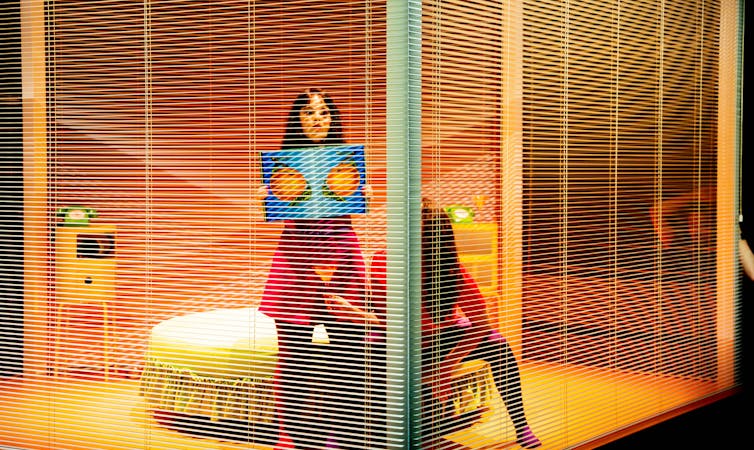

Among the local standouts was Private View by Adelaide’s Restless Dance Theatre. Their honest, gentle and confronting exploration of the ups and downs of love drew from the experiences and imaginations of the company’s troupe of dancers living with and without disabilities.

Matt Byrne

The work broke down barriers between audience and onlooker, able and disabled. It ended with many of us on our feet, dancing in a sea of confetti, joyous.

Matt Byrne

Another supremely memorable show from the independent sector was Grand Theft Theatre by Pony Cam, led by David Williams. With equal amounts of humour, charm and earnestness, highly skilled actor-dancers reminded us not just why we go to the theatre, but of how this experience can change lives.

It was a pleasure to also see work from VITALStatistix, a company that has been making high-quality, socially engaged work in Port Adelaide since 1984. The company’s I Hide in Bathrooms was staged in their home in the historic Waterside Worker’s Hall.

Writer/performer Astrid Pill offered a quirky, serious and moving take on life, partnership and death. We were left with an obvious but often overlooked truth: “We will all be left, and we will all leave.”

Sam Oster

International fare

Mackenzie brought in work by four of the established superstars of the international festival circuit: directors Barry Kosky, Robert Lepage and Thomas Ostermeier, and choreographer Akram Khan.

She also programmed a deeply satisfying selection of carefully crafted, timely works by smaller companies, mostly based in Europe.

Among the outstanding works in this category were Qui a tué mon père (Who Killed my Father) and Antigone in the Amazon.

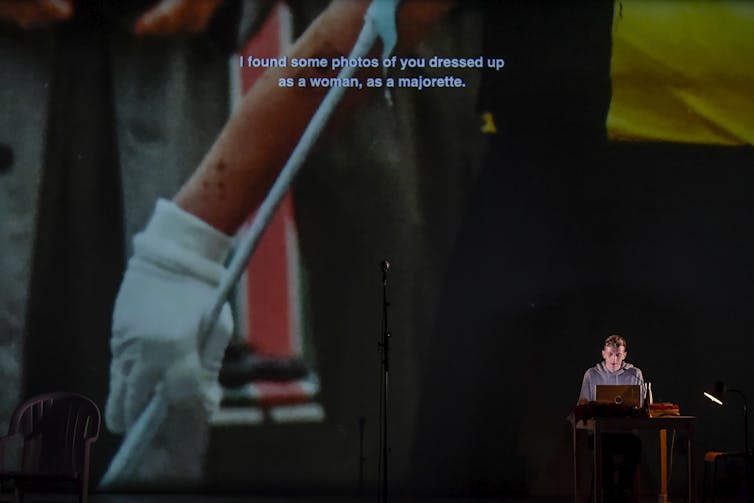

In the former, acclaimed German director Ostermeier teamed up with Édouard Louis in a theatrical adaptation of Louis’ novel. The writer himself narrated and enacted the story of his troubled relationship with his father, and of growing up gay in a conservative, working-class town a world away from Paris, condemned to “poverty, homophobia and conformity”. The work suggests the ultimate killers of his father were a long line of national leaders from Jacques Chirac to Emmanuel Macron.

Roy VanDerVegt

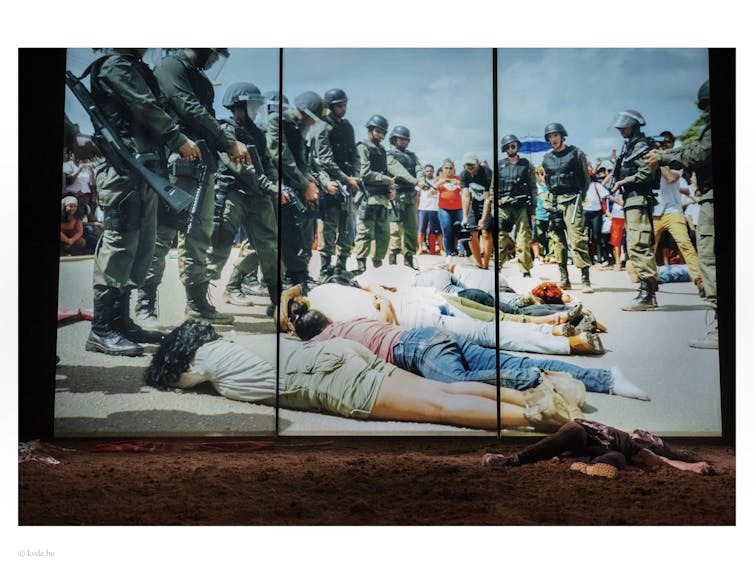

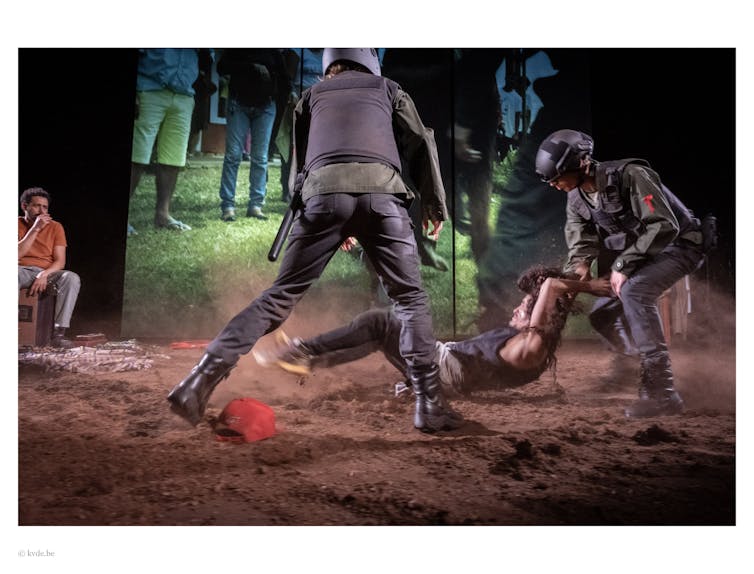

For me, however, the most emotionally taxing but rewarding work of this year’s festival was Antigone in the Amazon. It’s a collaboration between the Belgium company NTGent and the Amazonian activist group Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST).

Brilliantly directed by Milo Rau, the work offers complex, multi-layered insights into the ongoing battle between Indigenous peoples in the Amazonian rainforest and those profiting from the land through deforestation and habitat destruction. The dramatic recreation of a well-known massacre of 17 civilians in the state of Pará on April 17 1996 was masterfully paired with Sophocles’ ancient Greek tragedy, Antigone.

Kurt van der Elst

Live action was cleverly linked to videos shot in remote locations in the Amazon. In turn, the onstage actors appeared in sequences shot on location with actors associated with the MST.

Kurt van der Elst

The result was an uncanny and powerful doubling. Drawing from Sophocles’ play, the work concludes with the tragic observation that “the killers and the killed” are “all one family”.

Kurt van der Elst

The festival’s three big-ticket items were clear crowd-pleasers.

Berlin-based Australian Barry Kosky offered up a dark, brilliant staging of Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera. Actors moved up, down and across a massive black constructivist set, playing a game of cat and mouse that ends with the capture of arch-villain Macheath.

All are equally complicit in creating misery in this Weimar-era German classic, in which Kurt Weil’s lilting tunes contrast with Brecht’s hard-hitting lyrics to create that sense of estrangement Brecht is famous for.

Canadian director Robert Lepage’s The Nightingale and Other Fables came in two parts: a prelude of Russian folk tales, ingeniously presented with human bodies creating shadows, and a wildly extravagant staging of Igor Stravinsky’s short opera, The Nightingale.

Based on a Chinese classic tale, it tells the story of a nightingale (sung by soprano Yuliia Zasimova) who enchants the emperor and ultimately returns every night to sing to him.

Andrew Beveridge

Lepage’s staging relied on the charming and enchanting tradition of Vietnamese water puppetry. While puppets were manipulated from a pool of waist-deep water in the orchestra pit area, the stage of the Festival Theatre was filled to capacity with members of the State Opera of South Australia Chorus and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

It was a thrilling production with inventive and ingenious puppets of all sizes, even if excessive in its visual splendour at times.

Andrew Beveridge

Andrew Beveridge

Choreographer Akram Khan’s work famously builds on the vocabulary of the traditional South Asian dance, Kathak, as a basis for his company’s unique style of contemporary dance. His work Jungle Book reimagined is far from the Disney version.

In this darkly dystopian world, climate change has brought devastation to the planet. Humans are useful only for what they can teach the remaining animals.

Camilla Greenwell

Though I found the use of text intrusive and confusing at times, the dance work involved all the extraordinary precision, speed, athleticism and full use of the body associated with Khan’s choreographic practice.

Camilla Greenwell

An old vision realised

The depth, breadth, range, grit and good-heartedness of this year’s festival made me reflect on one of the most infamous of international festival fails: the dismissal of artistic director Peter Sellars in November 2001, months prior to the opening of the 2002 Adelaide Festival.

Sellars, who met great success as a theatre and opera director in Europe and his native US, had a compelling vision for an Adelaide Festival. He wanted one that was international, yet intensely local, and which featured new Indigenous Australian work.

Unfortunately, for a range of reasons – not least of which was a lack of understanding of how things work in Australia – Sellars was sent packing.

Some 22 years later, we have a festival that in many respects realises Sellars’ three-pronged vision. It’s made possible because Ruth MacKenzie and her team did their homework, and did it well.

Read more:

The magic tricks and the deep souls of theatre, dance and music at the 2024 Perth Festival

![]()

William Peterson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Adelaide Festival 2024: a moving marriage of local and international works – with Indigenous voices front and centre – https://theconversation.com/adelaide-festival-2024-a-moving-marriage-of-local-and-international-works-with-indigenous-voices-front-and-centre-226004