Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Elizabeth Reid Boyd, Senior Lecturer School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University

Valentine’s Day is associated with red and pink, representing passion and romance. But there’s another hue with a secret, sensual history longing for embrace: green.

The colour of nature and fertility, green is deeply connected to love in traditions throughout the world. In these times of conflict, 2024 is the year we should remember what connects rather than divides us, and embrace green as the colour of love.

Read more:

From Chaucer to chocolates: how Valentine’s Day gifts have changed over the centuries

Green is at the heart

In the ancient Indian chakra tradition, green is the colour of the heart. The heart organ has long been associated with love. A chakra, conceptualised as a wheel of whirling energy, balances particular emotions and the health of the body. The heart chakra at the centre of the chest represents loving-kindness, compassion and care.

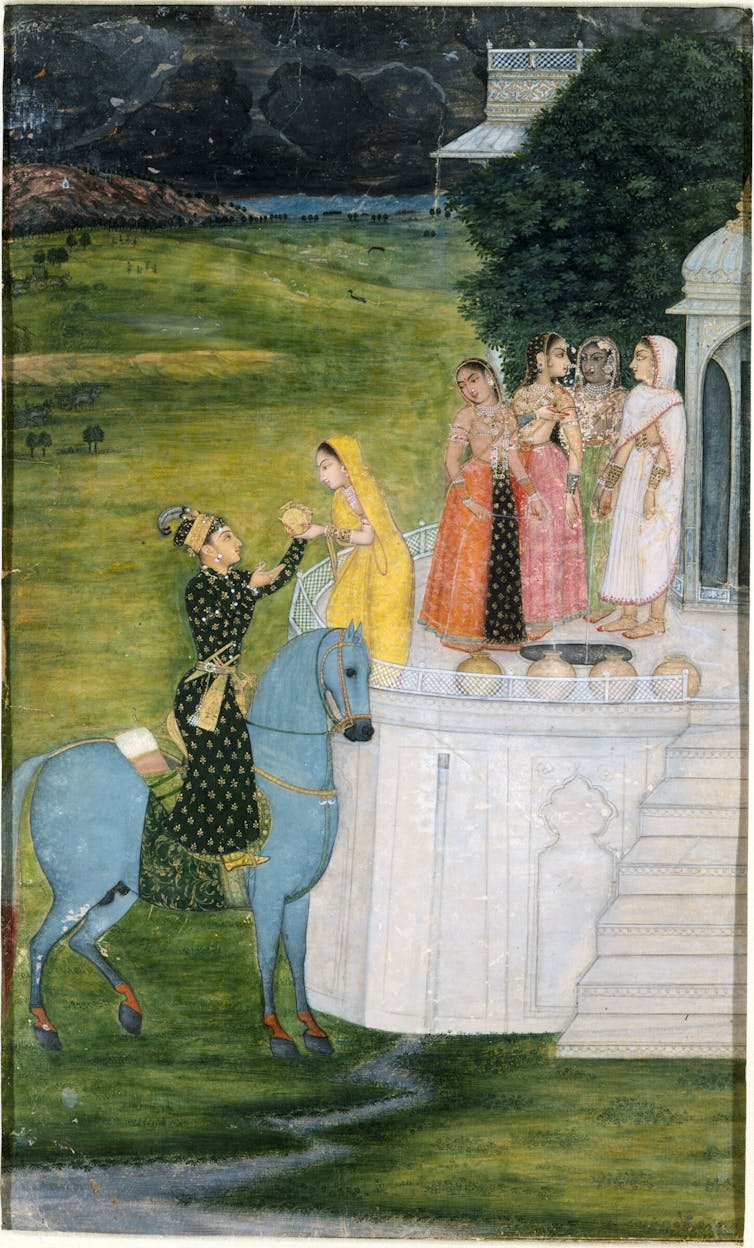

© President and Fellows of Harvard College, CC BY-NC-SA

Green has a range of cross-cultural meanings to do with balance, peace and hope. Islam associates heavenly paradise with the colour. It is important in the Catholic faith for hope and life, as in Judaism, where it means renewal. In China, jade is considered powerful and fortunate, as is pounamu jade in Maori culture. Scottish serpentine is still believed by some today to boost creativity.

In European mediaeval folklore, the colour was associated with both being lucky or unlucky in love. It symbolised a young woman’s sexuality, and being “greensick” was a term for a youth in unrequited love.

Mary Magdalene was depicted wearing green sleeves. Robin Hood and Maid Marian wore it in the greenwoods, the home of lovers.

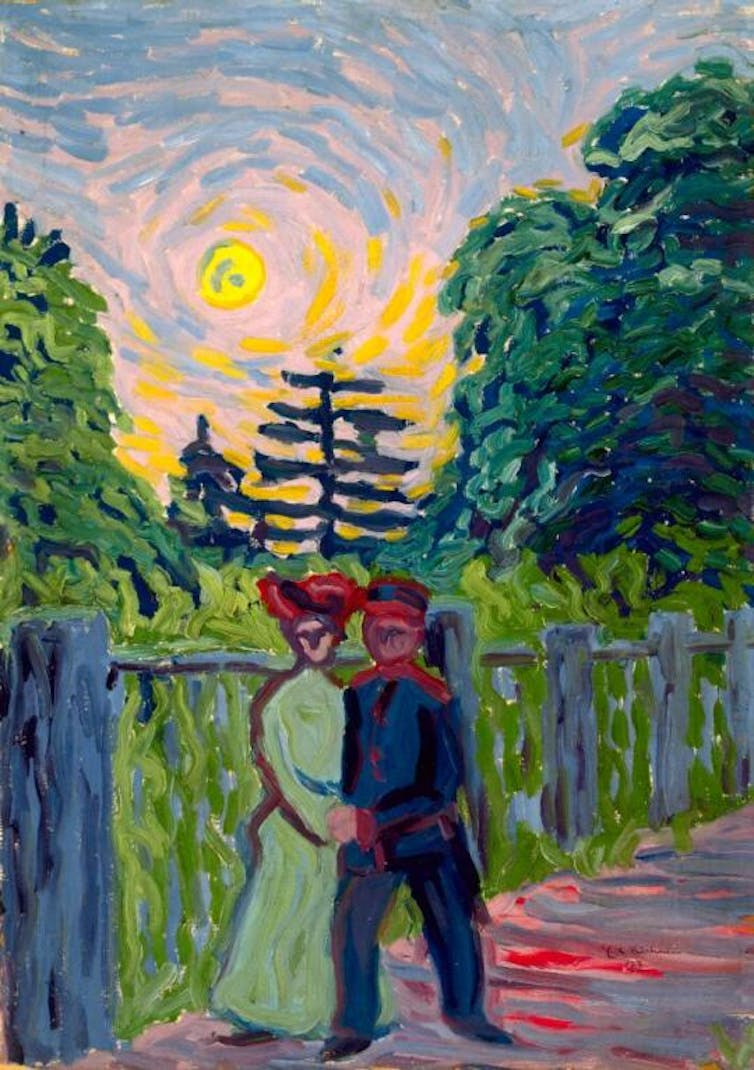

Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, CC BY

During the Renaissance, pastoral and woodland settings symbolised nature, pleasure, freedom and lack of convention, as Arden does in Shakespeare’s As You Like It and the forest in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: an alternative Green World, an erotic Eden.

Bawdy Renaissance madrigals such as Now is the Month of Maying included references to a “barley break” (a roll in the hay) and lads and lasses making merry upon the “greeny grass”.

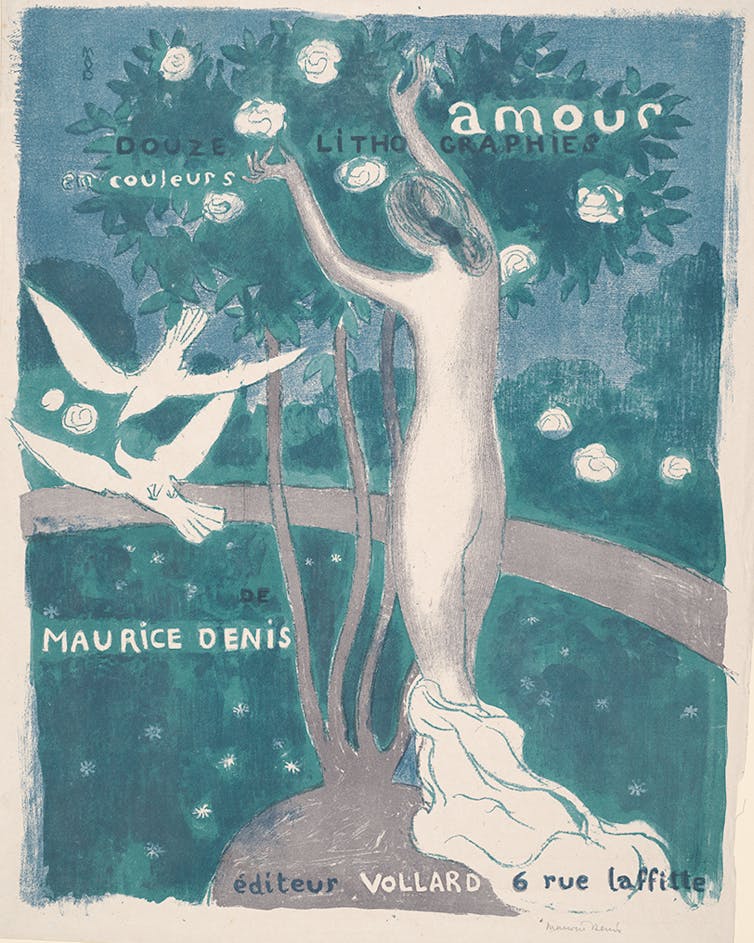

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Hidden greens

Old songs give us some clues to the secret, erotic symbolism of the colour green and its fateful relationship to women’s sexuality.

The Tudor version of Greensleeves contains suggestive lyrics regarding crimson stockings with gold above the knee and pumps as white as milk, and a grassy-green gown. According to a romantic myth, Henry VIII wrote Greensleeves to woo Anne Boleyn.

The lyrics go back to Celtic myths about the joining of the May Queen with the Oak King, also called the Green Man or “Jack in the Green”. Their union is consummated on May Day, also known as Beltane.

Rituals still practised today in magic and pagan communities connect May Day festivities to the hand-fasting or marriage of the god and goddess, encouraging desire to flame and convention to be cast aside outdoors.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Green in mediaeval times was also a sign of female promiscuity rather than free love. Wearing green reputedly signalled a woman’s willingness to make love, since it denoted fertility and the loss of virginity.

Green got a downgrade during the Middle Ages and beyond. Dubbed the fairies’ colour, who were associated with nature and said to be jealous of human good fortune, it became unlucky for brides and even today is warned against being worn at weddings.

Getty Museum

In the Middle Ages, healers and wise-women who held vital medicinal plant and herb use, as well as some who may have practised folk magic for alluring charms and love potions, were persecuted for their knowledge as witches. The female witch is so associated with green that in The Wizard of Oz she was given green skin.

A contradictory colour

Green carries negative connotations such as poison, jealousy and envy: the green-eyed monster.

Greenwashing or green-sheening are terms for the promotion of dubious environmental products. In Green Sense a treatise that explores botanical aesthetics, cultural studies academic John Ryan argues the contradiction of green comes from it being the shade of growth and decomposition: both birth and death.

Open Access Image from the Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University (photo: M. Johnston)

In The Key of Green cultural historian Bruce Smith suggests green has the power to upset. It has no fixed meaning and encompasses vast mental territory. Part noun, part adjective, part adverb and part verb, we see green, and we can also shop, build, vote and think green. We can feel green: during the Renaissance, he writes, being possessed by the passions was likened to wearing green spectacles. Smith also contends that we can hear colours: to hear green would be to listen longingly, as we do to love songs.

Green flags possibility for growth and change. It revives bodies and souls. In the philosophy of mediaeval mystic Hildegard of Bingen, viriditas – meaning greenness and vitality – signified the life force that makes all things fresh and new.

Getty Museum

Today greening power is being celebrated and revived. Across the globe, there are calls for the growth of love. Whether we celebrate our relationships in pastel or Barbie pink, passionate red, or all the colours of the rainbow, perhaps, this Valentine’s Day, we can widen our arms to embrace a little green.

Read more:

‘Freshly cut grass – or bile-infused Exorcist vomit?’: how crime books embraced lurid green

![]()

Elizabeth Reid Boyd does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. This Valentine’s Day, embrace green as the new colour of love – https://theconversation.com/this-valentines-day-embrace-green-as-the-new-colour-of-love-221003