Headline: South America’s Strategic Paradox. – 36th Parallel Assessments

Summary

Conventional wisdom believes that increased prosperity brings with it increased security. As individual, group and national material fortunes rise, domestic crime decreases and tensions ease between States. Yet, in South America improved macroeconomic indicators derived from increased trade within and from without the region have not followed convention. Not only has domestic insecurity increased, but the entrance of the People’s Republic of China as a major regional trade partner has heightened tensions with the United States, which sees a growing security threat associated with the PRC regional presence. Since the US adheres to the Monroe Doctrine as the basis for its regional security posture, this opens up the possibility of conflict with the PRC over its South American activities.

Source: Gateway to South America, 2018.

The Paradox Unpacked.

South America confronts a strategic paradox. It is not threatened by any significant extra-regional threats or serious inter-regional conflict (Venezuela’s threats to annex the oil-rich Essequibo region of Guyana notwithstanding). Its countries are members in good standing of many International organisations and conventions. It maintains deep cultural, diplomatic and military ties with extra-regional partners, including deepening diplomatic relations with the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) that will admit Argentina in 2024. It has extensive trade ties as an exporter and importer of primary and value-added goods within the region well as with extra-regional partners. These ties have extended beyond the traditional trade relationships with the USA and Europe to include the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Australasia (via the Transpacific Partnership Agreement—TPPA). With some notable exceptions (Bolivia, Brazil and Peru) it has had very few armed coups or revolutionary uprisings in a decade.

As a result, some consider South America to be on the global geopolitical periphery, while others see it as benefitting from non-alignment. The reality is more complex. Although not party to the major conflicts of the age, South America is deeply integrated into core geopolitical networks via memberships by countries and regional organisations in a latticework of international agreements, alliances, conventions, institutions and treaties covering the full scope of global endeavour, from climate change to military alliances. Specific engagements are aligned in different ways due to historical as well as practical reasons depending on the subject and national interests involved.

The paradox is that increased macroeconomic prosperity has accentuated domestic and regional tensions. It is part of a larger split in the world order that involves differences between the post-colonial Global South and the post-imperial Global North, a rift that has widened as the international system transitions from a unipolar to a multipolar realignment. The divide is seen in China’s growing presence in South America, something that is largely welcomed by regional diplomatic and business elites but has drawn negative attention from the hemispheric power that the PRC is eclipsing in terms of trade and investment—the US.

South America is also plagued by transnational crime, political-criminal networks, civil unrest and socio-economic deprivation leading to social disorder and high social violence levels, including homicide rates (one third of the world’s murders happen in Latin America). Recent wealth growth in South America has not translated into increased employment, wages or the provision of public goods and services paid out of tax revenues. Instead, relative deprivation has increased because rising social expectations are not met by improvements in material conditions for all. Instead, after years experimenting with market-driven macroeconomic policies (often first employed by authoritarian regimes with poor human rights records) and then an assortment of state-capitalist “correctives,” the region has a checkered record across a swath of socio-economic indicators: income inequality and wealth concentration, childhood poverty and infant mortality levels, education participation and literacy rates, access to electricity, potable water and sanitation facilities, etc. As overall wealth increased, so too has human insecurity.

Source: Quora.com.

This has happened during a period of relative political stability. The “Pink Tide” of indigenous socialists that came to power Latin America in in the early 2000s (exemplified by Hugo Chavez in Venezuela and Evo Morales in Bolivia) has given way to rightwing national populists (Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil), neo-libertarians (recently elected Javier Milei in Argentina), leftwing populist authoritarians (Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela), and mixes of centre-right and centre-left democratic coalitions in countries like Brazil, Chile and Ecuador (left-centre), or Peru, Paraguay and Uruguay (right-centre), with the elasticity of their respective commitments to democracy duly noted. Political competition is often raucous, but regime continuity has been the regional norm for the last twenty years.

Trade-based Prosperity.

South America has extensive trade links to the world and within the region itself. Its major regional trading bloc, MERCOSUR, is one of the world’s largest, with four permanent members (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay now joined by Bolivia) holding a combined GDP of USD$2.2.trillion, bolstered by trade with seven regional associate members. Other than Venezuela, all of the region’s States have a working relationship with the MERCOSUR trading bloc as well as participating in smaller trade networks. Having joined MERCOSUR in 2012, Venezuela’s membership was suspended in 2016 for non-adherence to democratic principles. South America also includes the Andean Community (CAN) and Latin American Integration Association (ALADI) as smaller sub-regional trading blocs, the combined total of which is to promote extensive cross-regional economic exchange.

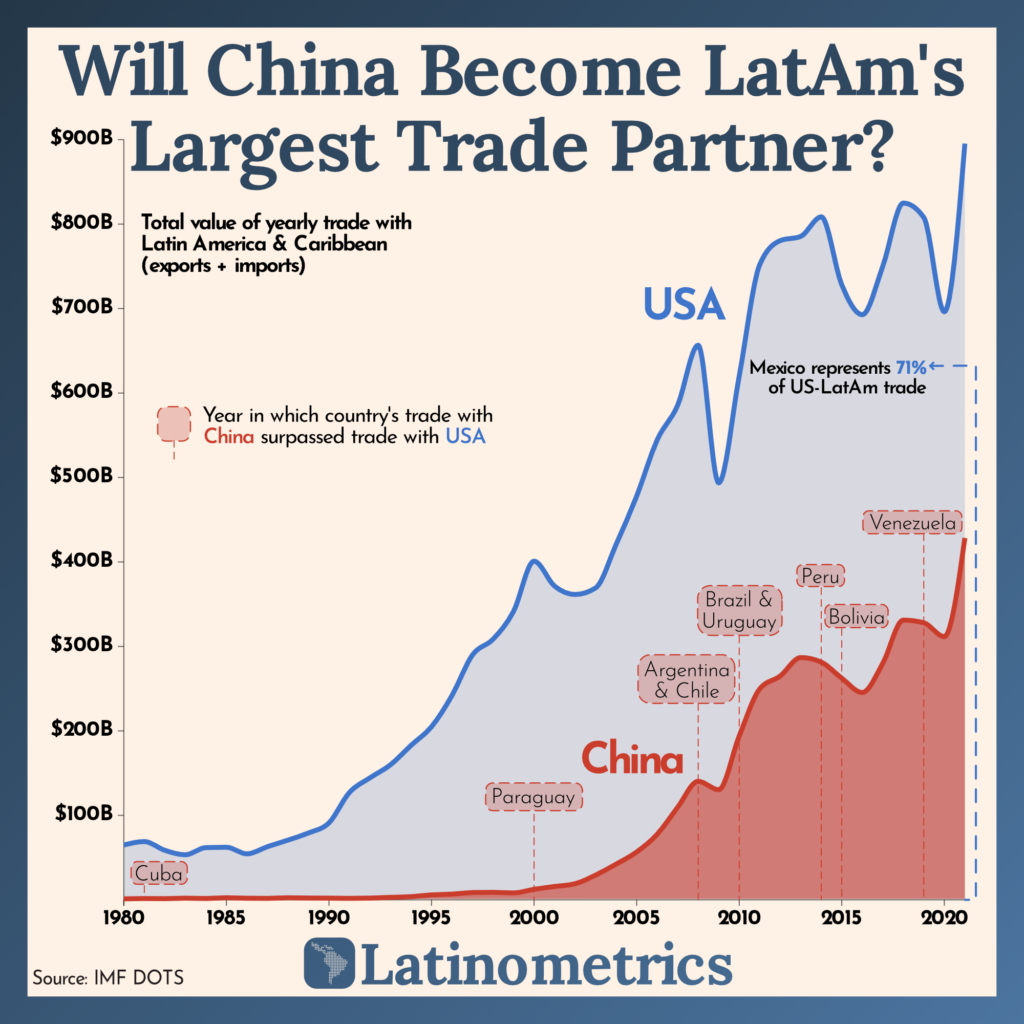

South America exports primary and value-added goods to the EU, North America and Asia, with investment flows and value-added products coming into the region primarily from the US, People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the European Union (EU). In the last 20 years the PRC has overtaken the US as South America’s main trading partner in exports and imports, with nineteen countries signing up to the Belt and Road Initiative. The volume of trade between South America and the PRC rose from US$14 billion in 2000 to US$500 billion in 2022. Eight South American countries now have “strategic partnerships” that have made the PRC their largest trading partner and in 2022 Latin American-PRC trade exceeded US-Latin American trade by USD$72 billion.

Even so, the USA accounts for 22 percent of Latin American foreign trade (mostly with Mexico) and retains its dominant position as South America’s main foreign interlocutor when factoring in other exchanges involving diplomatic and military relations, professional services, dollar remittances and cultural interactions (e.g. concerts and other artistic endeavours). In 2020-21 the volume of trade between South America and extra-regional partners briefly dropped as a result of the Covid pandemic’s impact on supply chains, but it has returned to surpass pre-pandemic levels even if the total value of South American trade in 2023 is less than previous year because of price deflation and low (1.7 percent) annual GDP growth.

Foreign investors have recently focused on lithium and other strategic mineral extraction as well as forestry, fuel and agricultural export sectors. PRC firms have joined Australian, European and US firms in developing brine-based extraction facilities in the so-called “Lithium Triangle” encompassing NW Argentina, NE Chile, Western Bolivia and SE Peru. There is potential for more expansion of the sector, and Chile has moved to nationalise the industry within its borders. However, the surge in extractive enterprises has seen increased environmental damage (groundwater pollution in particular), something that has caused backlash from environmental and indigenous groups connected to the lands in which they are located. That constitutes a political problem for the elected governments that govern them.

Moreover, as trade linkages increased, so has the presence of transnational and domestic organised crime. To “traditional” illicit trade such as narcotics, which itself has increased significantly in the last decade, there are now added an assortment of other criminal enterprises that use legitimate commercial trade conduits as covers for their activities. Fisheries poaching, animal, human and weapons trafficking and an assortment of other black market enterprises have been added into the mix. The Hezbollah presence in the Tri- border area joining Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay is a salient example of the criminal/ideological nexus.

Similarly, construction of modern container terminal facilities by PRC firms has facilitated increased volumes of goods arriving in South American ports, but has not been matched by increases in resources, personnel or the efficiency of administrative agencies responsible for trade. Corruption permeates customs and border control units in spite of government promises to clean up their respective sectors, so the problem is compounded rather than mitigated by the advances in trade volumes within and from without the region. One specific concern is that container terminals built along the Panama Canal and at several South American ports may be used for criminal as well as legitimate ends given lax enforcement capabilities.

To be sure, increases in foreign trade and investment and entrance of the PRC into South American markets have brought material benefits to the region. But PRC investment is focused on capital-intensive infrastructure (such as power plants), extractive and logistics activities that has resulted in increased income inequalities because employment opportunities are limited, elites monopolise revenue streams derived from those sectors, tax evasion is rampant and environmental degradation and land dispossession are closely associated with the industries in which investment is concentrated. Even as a trickle-down effect, trade-driven economic prosperity has not produced the anticipated results.

Instead, material hardship has produced mass migrations throughout South America. Venezuela has lost 7 million people under the Maduro regime, with most heading to Colombia, the US and Chile. Argentines and Peruvians have flocked to Chile because of its relative stability and growth, and Paraguayans and Uruguayans have sought greener pastures in their larger neighbours as well as further abroad. For Brazilians, the destinations of choice are the US and Portugal (which also serves as a gateway into the Eurozone). For many recipient countries, the presence of thousands of non-citizen migrants poses grave challenges to public good and services provision, stretching many of them to the breaking point. That is believed to contribute to increased crime, disorder and ethnic/nationalist conflict between native-born locals and foreign migrants. Accordingly, migration has turned into a regional security issue.

The Security Dilemma.

Arrival of the PRC as a South American trade and investment partner produced an adverse reaction on the part of the US. The US sees pernicious effect in Chinese “dollar” and “debt” diplomacy, where PRC-partnered firms, national and/or state governments are offered favourable terms for PRC direct economic assistance and infrastructure development loans that sometimes includes unduly influencing local officials responsible for approving and administering those projects. Dollar diplomacy is seen as contributing to South America’s culture of corruption, much in the way PRC dollar diplomacy is viewed in Subsaharan Africa, South Asia and Pacific Island nations. Moreover, the debt side of PRC loan facilitation can result in debt traps, where unserviceable loans are traded for equity swaps in sectors where the PRC has financially contributed, again along lines seen elsewhere. Since debt swaps occur in strategically important sectors, that makes them a threat to national sovereignty and hence a security concern.

Many Chinese projects in South America have “dual use” potential that can serve military/security as well as civilian purposes. Along with investment in modernising sea- and airports, key examples of this are, most broadly, the prevalence of Chinese telecommunications firms in South American broadband networks and, more specifically, PRC satellite tracking facilities erected in Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Venezuela (and Cuba) over the last fifteen years in addition to space research partnerships with Brazil and Chile that grant Chinese access to jointly operated ground stations in those countries. The PRC-operated signals stations are controlled by Chinese intelligence services, are staffed by Chinese nationals and are suspected of engaging in electronic and technical eavesdropping on regional communications as well as undertaking offensive and defensive tasks (such as hacking and jamming) that integrate with PRC military assets in space and in the oceans surrounding the continent. Chinese surveillance systems are also used by South American domestic security services, leading to concerns that they may be employed in invasive ways and/or are being accessed and data mined by PRC intelligence via embedded “backdoors” in them.

PRC Signals Collection Land Base, Bajada del Agrio, Neuquen, Argentina. Source: The Storiest, December 2022.

To this is added US concern about the potential for the PRC to establish military bases in South America. A recent PRC proposal to build a PLAN naval facility in Ushuaia, in Argentine Tierra del Fuego, has raised concerns about their ability to project force across the strategic Magellan Strait choke point and onto Antartica.

That creates a “security dilemma.” It is a situation where a State, perceiving that a rival seeks military-security advantage over it, prepares for impending conflict by increasing its full-spectrum fighting capabilities. Seeing that the first State is bolstering its forces, the rival responds in kind, leading to a tit-for-tat arms race and a greater possibility for miscalculations leading to conflict. Whatever eventuates, what matters here are perceptions of threat and planning for conflict rather than the actualities of threat when it comes to force projection.

Entrance of the PRC as a trading partner, strategic investor and diplomatic interlocutor in South America is seen by the US as a threat to regional stability, thereby making South America a potential contestation zone. There is real possibility that a regional security dilemma is in the making. Recent statements by senior US military officials confirm this view.

Issue linkage and decoupling.

“Issue linkage” in international affairs refers to a negotiating strategy where one issue (migration) is linked to another (climate change) in order to facilitate agreement on both; and to concrete outcomes where two or more issues are linked in practice (say, trade and security). The historical record is for security partners to preferentially trade with each other and vice versa. The bipolar trade and security arrangements of the Cold War are a classic example of the practice. However, in the 1990s some countries including New Zealand began to de-couple their trade and security alignments. They separated their trade portfolios from their security commitments, figuring that the post-Cold War environment eased tensions on a global scale that permitted a move towards more elastic types of linkage.

The underlying assumption for de-coupling was that it would supersede rather than counterpoise trade and security commitments. In simple terms, countries would try not to straddle the divide between antagonistic foreign partners, but instead would “silo” approaches to them so as to insulate one issue from the other. Or, they would create parallel trade/security linkages with different partners as circumstances dictated.

However plausible this may have been in theory, South American embrace of the PRC as a trade partner has alarmed the US. The result is a perverse issue-linkage where the growth of PRC-South American trade and investment is seen by the US as a potential pathway to an increased PRC military-security presence in the region. Given continued US adherence to the 1823 Monroe Doctrine when it comes to hemispheric security (which affirms that the US will militarily resist attempts by non-hemispheric powers to establish a military presence in the Western Hemisphere), that offers a chilling prospect for regional peace.

Problems of Governance and Democratic Backsliding.

The South American strategic paradox (increasing prosperity/increasing insecurity) is grounded in its mixed governance record. While relative democratic stability in the majority of countries freed citizens from the fear of state violence and gave them nominal voice in selecting their political leaders, democracy has not universally brought with it improved transparency, lesser corruption and more accountability in government (Chile and Uruguay being exceptions). In some cases it replaced dictatorial practices with an electoral veneer that better disguised the self-serving behaviour of economic and political elites.

This has led to a regional phenomenon known as “democratic backsliding,” a process in which democracies are undermined from within by presidential imposition, so-called “constitutional coups” (where legislatures manufacture justifications and use institutional procedures to impeach and remove presidents), and by a general “hardening” of the institutional order when it comes to accountability and transparency. Government processes become increasingly opaque and unresponsive to the popular will. Nepotism, patronage and clientelism rival meritocratic criteria for social and bureaucratic advancement. Efficiency in the provision of public goods and services is reduced and black and grey (informal) markets expand. In response, crime rises, disillusioned populations lose faith in democracy and disenchanted groups adopt nihilist social and political attitudes rooted in a sense of survivalist alienation. In effect, inequality, indifference and lack of opportunity undermine good governance.

To recap: improved macroeconomic conditions boosted by increased trade have not extended to South American masses in the form of growing employment, rising wages and better public services. Corporate and individual tax evasion remains a hemispheric problem. Corruption is endemic and resources to combat crime and increase official transparency and accountability are insufficient in most countries. That prevents States from controlling their borders in efficient fashion, so the foreign trade sector becomes a magnet for illegal activities.

That is the ultimate cause of South America’ strategic paradox. Lacking responsive government and effective regulatory enforcement, the benefits of trade have not served the regional commonweal and instead have exacerbated social inequalities that increase domestic insecurity. The emergence of the PRC as the region’s largest trading partner has also caused a defensive security reaction from the US that has the potential to cause a regional security dilemma. Macroeconomic growth in South America may have improved thanks to the upsurge in foreign trade, but increased regional security has not come with it.

NOTES

1 Andres Malamud and Luis L. Schenoni, “Latin America is Off the Global Stage and That is OK,” Foreign Policy, September 10, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/10/latin-america-global-stage-imperialism-geopolitics/

2 For an early analysis of the contradiction, see Laura Jaitman and Stephen Machin, “Crime and Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: towards evidence-based policies,” CentrePiece, Winter 2015/2016 https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cp461.pdf.

3 CEPALSTAT, Statistical Databases and Publications. United Nations, ECLASC/CEPAL, November 2023. https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?theme=1&lang=en.

4 Council on Foreign Relations, “Mercosur: South America’s Fractious Trade Bloc,” Backgrounder, May 9, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/mercosur-south-americas-fractious-trade-bloc.

5 US House of Representatives, Foreign Affairs Committee, “China Regional Snapshot: South America,” Foreign Affairs Committee Media Centre Press Release, October 25, 2022. https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/china-regional-snapshot-south-america/

6 United Nations, ECLAC, “Value of Latin America and the Caribbean’s Goods Exports Will Fall 2% in 2023 in a Context of Great Weakness in Global Trade,” CEPAL, Press Release, November 2, 2023. https://www.cepal.org/en/pressreleases/value-latin-america-and-caribbeans-goods-exports-will-fall-2-2023-context-great.

7 Nicolas Devia-Valbuena and General Alberto Mejia, “How Should the US Respond to China’s Influence in Latin America?” United States Institute for Peace, August 28, 2023. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/08/how-should-us-respond-chinas-influence-latin-america.

8 Cate Cadell and Marcelo Perez del Capio, “A growing global footprint for China’s space program worries Pentagon,” Washington Post, November 21, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2023/china-space-program-south-america-defense/?itid=hp_only-from-the-post_p004_f001.

9 Jeff Seldin, “China Infiltrating US “Red Zone” With Latin American Push,” Voice of America: Americas, August 4, 2023. https://www.voanews.com/a/china-infiltrating-us-red-zone-with-latin-american-push/7212335.html.

10 Guillermo Saavedra, “China Pressures Argentina to Build Naval Base,” Dialogo Americas, January 3, 2023. https://dialogo-americas.com/articles/china-pressures-argentina-to-build-naval-base/.

11 John Grady, “Chinese Actions In South America Pose Risks to US Safety, Senior Military Commanders Tell Congress,” US Naval Institute News, March 8, 2023. https://news.usni.org/2023/03/08/chinese-actions-in-south-america-pose-risks-to-u-s-safety-senior-military-commanders-tell-congress.

12 Giovanni Maggi, “ Issue Linkage,” in Kyle Bagwell and Robert. W. Staiger, eds. The Handbook of Commercial Policy, Vol. 1, Part B, pp. 513-564. Elsevier/ScienceDirect, 2016. https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/2022-10/IssueLinkageDraft_041216.pdf.

13 Mainwaring, Scott and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. “Why Latin America’s Democracies Are Stuck.” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 34, N. 1, 2023, pp.156-170. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2023.0010.

14 For an early discussion of this syndrome, see Paul G. Buchanan, “That the Lumpen Should Rule: Vulgar Capitalism in the Post-Industrial Age,” Journal of American and Comparative Cultures, V.23, N.4 (Winter 2000), p.1-14. https://www.proquest.com/openview/3e47ea2c49d289b57f0641c02cc8b592/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29587

15 Adriana Arreaza Coll, “Latin America’s Inequality Is Taking A Toll on Governance,” Americas Quarterly, February 8, 2023. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/latin-americas-inequality-is-taking-a-toll-on-governance/#:~:text=Low%20educational%20and%20occupational%20mobility,in%20income%20in%20the%20world.

Analysis syndicated by 36th Parallel Assessments –