Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Amanda Nettelbeck, Professor of History, Australian Catholic University

National Archives of Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of deceased people.

For many non-Indigenous Australians, it might seem the Voice to Parliament – the first step in the Uluru Statement’s process of “voice, treaty, truth” – is a recent idea. Conservative voices have framed it as a dangerously untested prospect.

But as First Nations have always known, voice, treaty and truth carry long histories. They’ve long been at the centre of Indigenous rights campaigns in Australia. They’ve also existed in other settler nations like New Zealand and Canada where treaties were forged at the point of colonisation.

These histories remind us how long First Nations people have waited for political recognition in this country – and that, compared to other former colonial sites, Australia is the exception, not the rule.

The Larrakia petition

Calls for voice as political representation have been part of First Nations activism in Australia for at least a century.

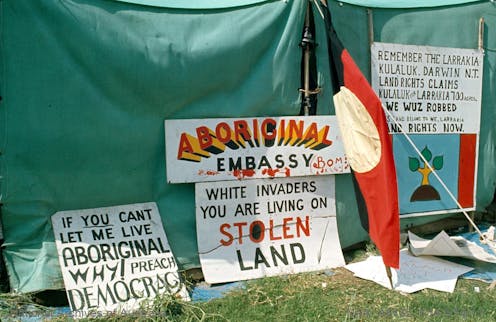

In the 1970s, Australian Aboriginal civil and lands rights movements harnessed long-running campaigns by Aboriginal activists calling for rights to treaty, land and political representation.

One famous example is the Larrakia petition to the queen, organised in 1972 to coincide with Princess Margaret’s royal visit. It carried more than 1,000 signatures.

It drew the queen’s attention to the failure of the British Crown to sign treaties with Indigenous peoples in Australia, unlike in New Zealand and North America, and called for her assistance in achieving

land rights and political representation, now.

The Larrikia organisers waited patiently outside Government House in Darwin to hand the petition directly to Princess Margaret. When a police barricade prevented them and tore the petition, they taped it together and sent it directly to Buckingham Palace.

William Cooper’s petition

Decades earlier, Yorta Yorta civil rights activist and co-founder of the Australian Aborigines’ League, William Cooper, spent the mid-1930s collecting more than 1,800 signatures from Indigenous communities across Australia for a petition to the king.

It urged the Crown to safeguard the interests of Aboriginal people as the original heirs and successors of the land and called for Indigenous political representation in the federal parliament.

As with the Larrakia petition, Australian government officials prevented the delivery of Cooper’s petition.

Even so, it remains a powerful reminder of the longevity of First Nations campaigns for a parliamentary voice. It also reminds us how long Australia has resisted activating one.

In other countries, it has been different

In Canada and New Zealand, the British Crown did make treaties with Indigenous peoples at the point of formal colonisation. In these countries, the right of political representation has not been contested in the same way.

That’s not to say these nations provide a direct model for Australia. Each country has its own history and political relationship between Indigenous peoples and government. And nobody’s suggesting treaties in other places fixed sovereignty disputes or guaranteed Indigenous rights.

But treaty rights dating back to the 1800s gave First Nations peoples in other settler colonial sites political leverage in a way Australia’s First Nations have been denied.

In Canada, First Nations treaty rights and rights of self-determination are enshrined in the Constitution. An elected Assembly of First Nations liaises with the federal government as the representative body.

In New Zealand, Māori have had dedicated parliamentary seats since the 1860s. Political representation is enshrined in the Māori Representation Act 1867, which gave all Māori men the right to vote.

Colonial officials originally conceived the Māori Representation Act 1867 as a way to bring Māori into the colonial political system rather than as a vehicle for an independent political voice.

Despite its colonial underpinnings, it shows how a formal avenue of Indigenous political representation existed almost from the beginning of the colonial relationship in a setting where treaty existed.

This raises the longer history of treaty discussions in colonial Australia.

Australia’s missed opportunities for treaty

Australia was exceptional in Britain’s settler empire for having no formal history of treaty between Indigenous peoples and the Crown.

The doctrine of terra nullius, or land belonging to no one, was how Britain claimed possession in 1788.

But that doctrine did not necessarily hold true in perpetuity, and the continuing absence of treaties in Australia was not inevitable.

By the 1800s, the mood of the Colonial Office (the British government department that managed colonies) had shifted.

In the early 1830s, Tasmania was coming through its devastating land wars. This experience motivated Tasmania’s Governor George Arthur to write to the Colonial Office in London. He suggested treaty arrangements should be made with Indigenous peoples in the territories of western and southern Australia to avoid a similar risk.

Arthur’s intervention dovetailed with a larger agenda for colonial reform after the abolition of slavery, and the British imperial government was receptive to his advice.

In 1835, the Colonial Office told South Australia’s colonisation commissioners that the Crown would not sanction British settlement there unless they could show they would protect Aboriginal people’s

earlier and preferable title.

The colonisation commissioners committed to purchase Aboriginal lands on those conditions. But because colonial authorities decided “earlier and preferable title” did not exist according to the law of possession, these purchases didn’t happen.

The year 1835, then, was a turning point. Treaties might have been forged with Indigenous peoples in the new colony of South Australia, but they were not.

Instead, the Crown tried to mitigate problems of frontier warfare by claiming Aboriginal people as British subjects who would receive equal protection under the law.

This became settled colonial policy across Australia, although it was almost never realised in practice.

Read more:

In the 1800s, colonisers attempted to listen to First Nations people. It didn’t stop the massacres

Truth: resetting the relationship, not just the record

This brings us to the question of truth. When we speak about remembering past injustices – especially the history of colonial land wars – it’s often presented as uncovering a hidden or secret history.

But in 19th century Australia, the frontier wars were far from secret. Colonial authorities constantly debated the problem. Until the end of the 19th century (and later in northern Australia), it was one of the most persistent topics in official correspondence and the colonial press.

What’s missing from the colonial records are the voices and perspectives of the Indigenous communities who experienced the frontier wars.

These histories, however, have always had a strong presence in Indigenous intergenerational knowledge, as well as the intergenerational knowledge of settler-descended communities where these events occurred.

Legal scholars Gabrielle Appleby and Megan Davis have emphasised that the value of truth is not just in resetting the historical record but in constructively resetting the relationship between First Nations and the rest of the nation.

The longer histories of voice, treaty and truth tell us the time for politically constructive reform is well overdue.

![]()

Amanda Nettelbeck receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Voice, treaty, truth: compared to other settler nations, Australia is the exception, not the rule – https://theconversation.com/voice-treaty-truth-compared-to-other-settler-nations-australia-is-the-exception-not-the-rule-206092