Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jonathan Nott, Professor of Physical Geography, James Cook University

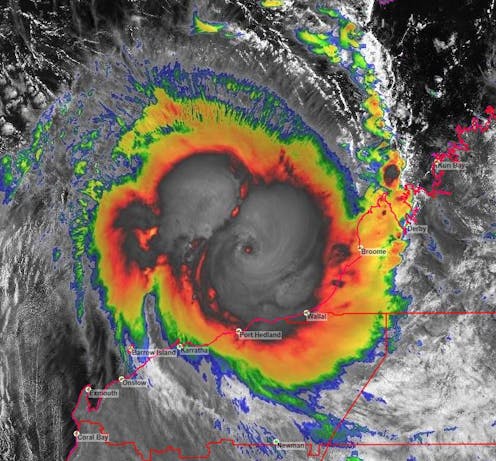

BoM

Residents along Western Australia’s northwest coast are bracing for Tropical Cyclone Ilsa, which is expected to be one of the most destructive storms to strike the region in more than a decade.

The Bureau of Meteorology says Cyclone Ilsa has intensified and is now classed as a category-four system. It’s forecast to cross the WA coast between Port Hedland and Bidyadanga Thursday night or Friday morning.

Tropical cyclones are huge low-pressure systems that form in tropical waters. They can bring extreme winds, heavy rain and damaging waves, destroying infrastructure and the environment and causing injury and death.

Let’s take a look at how Cyclone Ilsa developed, and what we can expect from cyclones in this region in future.

Why did Cyclone Ilsa intensify?

Tropical Cyclone Ilsa is the first system of category-four or higher to cross Australian shores since Cyclone Trevor crossed the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria in 2019.

Ilsa formed off the Northern Territory coast before tracking southwest towards Western Australia’s Kimberley region. It developed quickly on Tuesday into a category-two system, which involves wind gusts between 125 km/h and 164 km/h.

The cyclone intensified to a category-four storm on Thursday, which involves winds gusts between 225 km/h and 279 km/h. This was due to two main factors: high sea-surface temperatures and favourable conditions in the upper atmosphere.

Tropical cyclones (TCs) require sea-surface temperatures above 27℃. This provides warm, moist air that generates a massive amount of energy and fuels the cyclone.

Upper atmospheric conditions influence wind speed. Air is drawn in toward the centre of a tropical cyclone. In the Southern Hemisphere, the air spirals upwards in a clockwise direction then moves outwards to the upper troposphere, away from the storm. This air is known as “outflow”.

Cyclone Ilsa’s path led it into a region where the upper level wind was relatively light, which enhanced outflow.

As air moved outwards, more wind or “inflow” was drawn toward the centre of the system from the sea surface, bringing warmth and moisture. This enabled Cyclone Ilsa to rapidly intensify.

Australia’s cyclone capital

Northwest WA is Australia’s most cyclone-prone region. Records since 1970 show about 75% of severe cylones to make landfall in Australia occur in this region.

But why? It comes down to two things: the high sea surface temperatures in this part of the Indian Ocean, and the orientation of the coast.

Tropical cyclones tend to move polewards and, in the Southern Hemisphere, often curve southeast. The coast of northwest WA is oriented northeast/southwest, and so perfectly aligned to intercept these cyclones.

Several intense tropical cyclones have developed in the warm waters off northwest WA in recent years. However, the number to reach land in this region has been lower than average. That’s because mid- to higher-level atmospheric winds that steer tropical cyclones have directed many of them away from the WA coast.

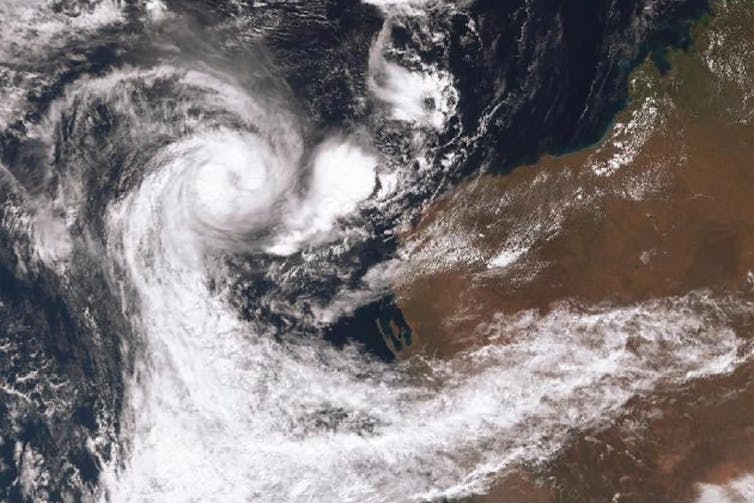

BoM

What about climate change?

Climate change is expected to change tropical cyclone patterns. The overall number is expected to decrease, but their intensity will likely increase, bringing stronger wind and heavier rain.

More intense tropical cyclones are expected because higher sea-surface temperatures will make the atmosphere more warm and moist. Cyclones thrive in such conditions.

But the general frequency of tropical cyclones is expected to reduce under climate change in most ocean basins, including the Indian Ocean.

Tropical cyclones usually form when there’s a large difference between temperatures at Earth’s surface and the upper atmosphere. As the climate warms, this temperature difference is likely to narrow.

Research last year showed the annual number of tropical cyclones forming globally decreased by about 13% during the 20th century compared to the 19th.

The activity of tropical cyclones in any one ocean basin over a year is measured by what’s known as the “Accumulated Cyclone Energy” or ACE Index.

The index is calculated by measuring the cyclone’s wind speed every six hours squaring it, then adding these values together.

A study has shown the index values for cyclone activity in the Southern Indian Ocean have decreased significantly since 1990.

I specialise in reconstructing long-term natural records of extreme events. Research by myself and colleagues has shown tropical cyclone activity along the WA coast is at its lowest level since approximately 500 CE – about 1,500 years ago.

Read more:

Cyclone Seroja just demolished parts of WA – and our warming world will bring more of the same

We’re not off the hook

Tropical cyclones maintain energy over warm water, and lose energy once they move over land or over cooler oceans.

Cyclone Ilsa is expected to weaken overnight on Friday as it moves east into the Northern Territory.

Climate change will lead to fewer tropical cyclones overall. But those that do occur will be more intense and damaging. So unfortunately, WA can expect regular cyclone impacts even as the climate warms.

Read more:

Tropical cyclone frequency falls to centuries-low in Australia – but will the lull last?

![]()

Jonathan Nott does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Anatomy of monster storm: how Cyclone Ilsa is shaping up to devastate the WA coast – https://theconversation.com/anatomy-of-monster-storm-how-cyclone-ilsa-is-shaping-up-to-devastate-the-wa-coast-203678