Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Duncan Cook, Associate professor, Australian Catholic University

Shutterstock

Mercury is a toxic heavy metal. When leached into the natural environment, it accumulates and builds up through food chains, ultimately threatening human health and ecosystems.

In the last century, human activities have increased atmospheric mercury concentrations by 300-500% above natural levels.

However, in some parts of the world, humans have been modifying the mercury cycle for thousands of years. This anthropogenic (human-caused) mercury use has led to mercury entering places globally it wouldn’t otherwise be found, such as in lakes or soils in remote locations.

One region with an especially long (but poorly documented) history of mercury use is Mexico and Central America. Early Mesoamerican societies such as the Olmec had been mining and using mercury in southern Mexico as early as 2000 BCE.

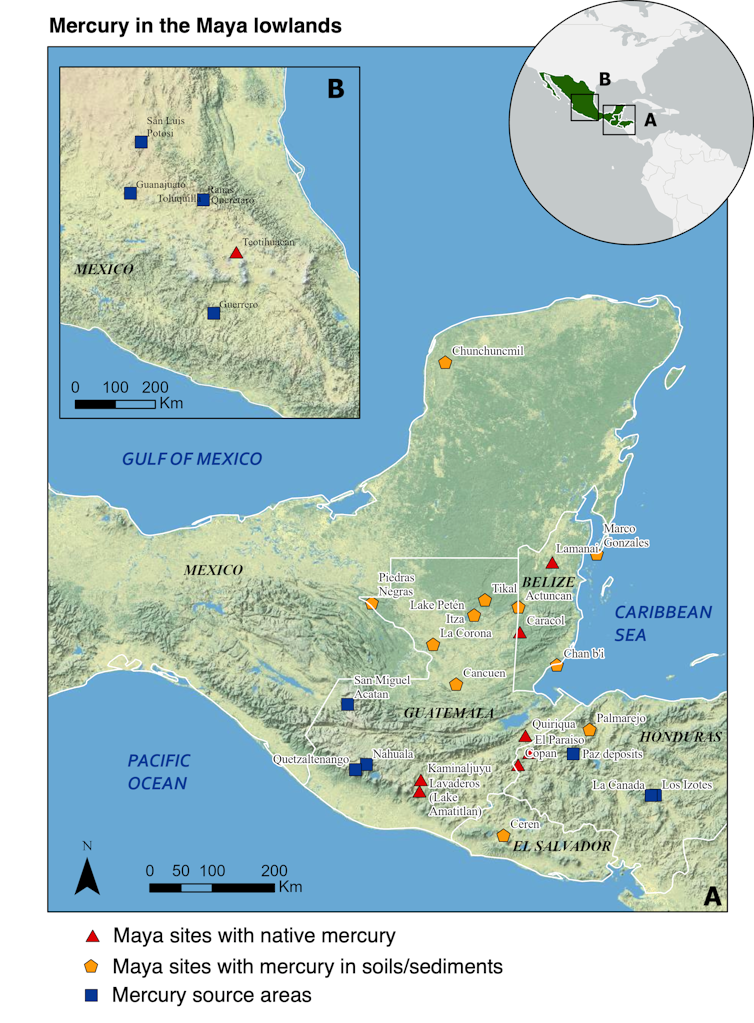

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.986119/full, Author provided

In our research, published in Frontiers in Environmental Science, we review the ways the Maya used mercury, the mystery of how they sourced it, and the environmental legacy of past mercury use.

Our present mercury problem has a deep legacy. Understanding its origins will also help us understand the trajectory of humanity’s fascination with, use of – and abuse of – this mercurial element.

Read more:

How poisonous mercury gets from coal-fired power plants into the fish you eat

Cultural and creative importance

Archaeologists have been finding mercury at archaeological sites in Mexico and Central America for more than a century.

The most common form reported is cinnabar (mercury sulfide, or HgS), a bright red mineral used extensively by the ancient Maya for decoration, craft, and ritual purposes such as burials and in tombs.

Maya Gallery, National Museum of Anthropology/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

It has been far less common to find liquid (elemental) mercury. There are only seven occurrences of liquid mercury at Mesoamerican sites that we are aware of.

But it’s feasible there may have been many more – and that it’s simply invisible in today’s archaeological record. Liquid mercury from 1,000 or more years ago could have evaporated or oozed away into the environment through time.

Exceeding toxic levels

Most Maya settlements were great distances from known mercury sources located in Mexico and Honduras, and perhaps Guatemala and Belize. This means the production, trade, and use of mercury would have been highly valuable and logistically challenging – especially for managing toxic liquid mercury!

Over the past two decades, scientists working on Maya archaeological projects have tested artefacts, soils, and sediments for their chemical properties, including for mercury, to better understand past human activities.

They test soils and former Maya areas excavated from far below today’s ground surface, which tell us about mercury levels during the Maya’s time.

Nick Dunning

Combined data from these tests show most Maya sites have some amount of mercury enrichment in buried soils. Specifically, seven out of ten sites were found to have mercury levels that equal or exceed modern benchmarks for environmental toxicity.

Locations with elevated mercury are typically areas the Maya occupied, including domestic patios, dating to the Late Classic (600-900 CE). Mercury also made its way into some drinking water sources including central reservoirs at Tikal.

While the appealing red cinnabar ore is the likely culprit of mercury pollution, the equally appealing and shimmering liquid mercury is another possible source of persistent pollution in some locations, such as Lamanai in modern-day Belize.

MarcelClemens/Shutterstock

At more complex sites, elevated mercury levels may be the result of both modern and ancient inputs. For example, it’s not clear if the mercury detected at the island Maya settlement of Marco Gonzalez (also in Belize) is from ancient or modern times.

Read more:

Belize shows how local engagement is key in repatriating cultural artifacts from abroad

Looming questions

Our work reveals a rich history of mercury use by the Maya and challenges the idea that pre-industrial societies didn’t have noteworthy impacts on their environments.

But there is much we still don’t know. Where and how did the Maya obtain mercury? Who mined it, traded it, and transported it by foot over hundreds of kilometres across present-day Central America?

Then there’s the question of whether the Maya were affected by mercury exposure. The next step will be for geochemists and archaeologists to track down the source of mercury at key sites and, if possible, scrutinise archaeological and human remains for signs of past mercury exposure.

We also need to find out what forms mercury takes in the environment today, so we can better understand where it came from, and provide guidance on what precautions (if any) need to be taken when working with legacy mercury.

Finding clues on early mercury use is crucial to understanding the interaction between legacy mercury and current mercury contamination in the environment today.

Read more:

Climate, conflict, collapse: how drought destabilised the last major precolonial Mayan city

![]()

Duncan Cook receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Nicholas Dunning works for the University of Cincinnati. His work related to Mercury in the Maya Lowlands has been funded by grants from the US National Science Foundation and the Wenner-Gren Foundation..

Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach works for the University of Texas at Austin, and received funding for this research from this university, the US National Science Foundation, and the National Geographic Society. She is affiliated with the American Association of Geographers.

Simon Turner received funding for this mercury research from The Leverhulme Trust.

Timothy Beach works for the University of Texas at Austin and worked for Georgetown University for 21 years, and received funding for this research from these universities, the US National Science Foundation, and the National Geographic Society.

– ref. Heavy mercury contamination at Maya sites reveals a deep historic legacy – https://theconversation.com/heavy-mercury-contamination-at-maya-sites-reveals-a-deep-historic-legacy-191325