Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Robert Horvath, Senior lecturer, La Trobe University

Alexander Zemlianichenko/Pool/AP

No concept is more central to Vladimir Putin’s propaganda today than “Russophobia”. Internationally and on the home front, his propagandists claim they are fighting “Russophobes”, enemies motivated by a visceral hatred of Russia’s culture and people. Last month, the Russian foreign ministry sanctioned 121 Australians (including me) for “forming the Russophobic agenda in this country”.

According to Putin, Russophobia is nothing less than an existential threat. Ukrainian Russophobia, he claimed last December, is a first step towards an anti-Russian genocide. On the eve of the war, he denounced “extreme nationalism’ for taking the form of “aggressive Russophobia and neo-Nazism”.

Then, as missiles began falling on Ukrainian cities, and Bucha and Mariupol became synonyms for atrocities, the spectre of Russophobia became both a justification for war and an explanation for international sanctions.

What is obscured by Putin’s conflation of Russophobia and neo-Nazism is the sinister lineage of his own vocabulary. Even as he was claiming to de-Nazify Ukraine, Putin was using terms that had been coined, shaped and popularised by the Russian far right.

What’s in a word?

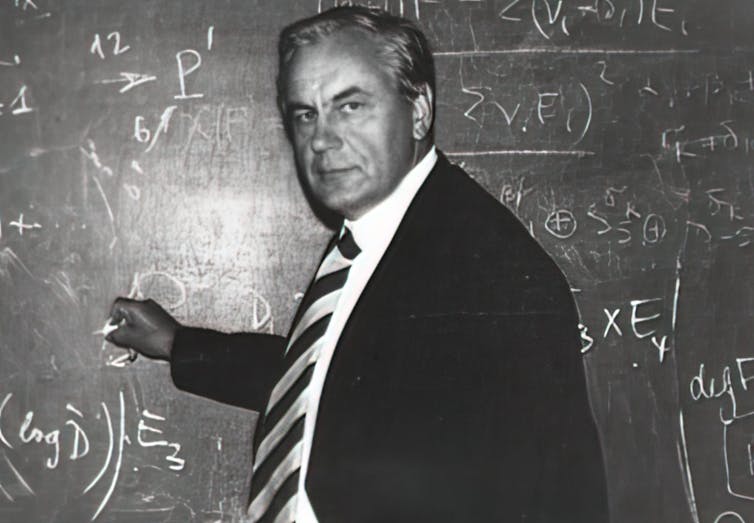

The modern usage of the term Russophobia can be traced to Igor Shafarevich, a Soviet-era dissident. Shafarevich’s long 1982 essay, Rusofobiya, was a response to a debate raging in samizdat (underground dissident literature) about the connection of the Soviet regime to the pre-revolutionary past. What incensed Shafarevich was how some participants in this debate depicted Russian history as a continuum of despotism stretching back via Stalin to Ivan the Terrible.

Shafarevich’s rebuttal of these “Russophobes” drew on the work of French conservative historian Augustin Cochin, who portrayed the French Revolution as a struggle between the “Small People”, the radical thinkers inhabiting salons and masonic lodges, and the “Great People”, the vast majority of the population.

Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

In Shafarevich’s account, Russophobes were analogues of Cochin’s “Small People”. But he also added an anti-Semitic smear. On the basis of a misleading selection of texts, he alleged that Russophobia was dominated by Jewish intellectuals whose hatred of Russia was inflamed by the Talmud and guilt about the role of Jews in the Bolshevik Revolution.

Shafarevich’s essay attracted little attention until the collapse of censorship during Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms. When a nationalist journal published Rusofobiya in 1989, it triggered an acrimonious debate between pro-Western liberals and Russian nationalists about the safest road out of totalitarianism.

This debate intensified after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin’s new democratic government was opposed by a “red–brown” coalition of neo-Stalinists and radical nationalists. Shafarevich was their leading ideologue. In the streets and in parliament, red–brown leaders used “Russophobia” as a rallying cry to denounce liberal reform and spread an anti-Semitic message about prominent reformers.

A grievance and a weapon

This struggle culminated in “Bloody October” in 1993, a constitutional crisis and the defeat of a red–brown uprising. The carnage ended Shafarevich’s political career, but Russophobia remained a powerful mobilising cause for anti-Western extremists of the left and the right.

On the left, the Communist Party expanded its definition of Russophobia to include hostility towards the Stalinist past. On the right, radical nationalists, traditionalist culture warriors and conservative clerics built reputations by fulminating against Russophobes.

Despite their political defeat in 1993, red–brown forces influenced the ideological agenda of the Putin regime. On the one hand, they waged a war of attrition against “systemic liberals”, advocates of market reforms and legislation targeting neo-Nazis. On the other, they became enablers of Putin’s crackdowns, vilifying pro-democracy campaigners in return for funding and access to the state media.

This collaboration intensified during the crisis that stretched from the massive pro-democracy protests in 2011–12 to Russia’s first attack on Ukraine in 2014.

Sergey Ponomarev/AP

In a bid to divide its opponents, the Kremlin posed as a defender of traditional values and focused popular anger on the anti-Putin performance by Pussy Riot in Moscow’s Christ the Saviour Cathedral. That transgression of sacred territory was misrepresented as a blasphemous assault on Russian traditions.

In the process, “Russophobia” was transformed from a grievance of radical extremists into a tool of state power. This shift was consecrated by a major conference on “Russophobia and the Information War against Russia” in September 2015 at Moscow’s Kremlin-owned Presidential Hotel. Never before had such a cross-section of Russia’s elite assembled to discuss Russophobia as a matter of political consequence.

What attracted less attention was that this forum was the brainchild of Aleksei Kochetkov, a militant whose career had begun in the red–brown opposition, as a member of a neo-Nazi party Russian National Unity (RNU). At the time, he boasted that RNU had chosen the swastika because it was a symbol of struggle “against world Jewry, the basic enemy of our people, an infection or a bacteria”.

Like many far-right militants, Kochetkov made a career under Putin as a facilitator of dictatorship. His speciality was “zombie election monitoring”, the enlistment of foreign extremists to legitimise unfair elections. Now he was influencing the regime’s information wars.

The greatest Russophobe?

The domestic crackdown that followed the invasion of Ukraine offered Kochetkov a new opening. After Putin vowed to cleanse Russian society of “scum and traitors”, Kochetkov returned to the Presidential Hotel for a conference on Internal Russophobia as a Threat to Russian Statehood. In his keynote address, he lambasted the enemy within – those who wanted to destroy the Russian state and bury the Russian people under its wreckage.

This conference marked a kind of apotheosis of Shafarevich’s ideas. The irony is that the anti-Russophobia crusade, which began as a rejection of stereotypes about Russia as a crucible of totalitarianism, has become a justification for a new totalitarianism.

As Putin pulverises the independent media, civil society and cultural institutions, his struggle against Russophobia is destroying the most humane tendencies in Russian culture. In the process, he has become the greatest Russophobe of all.

![]()

Robert Horvath receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Is Vladimir Putin the greatest Russophobe of all? – https://theconversation.com/is-vladimir-putin-the-greatest-russophobe-of-all-186642