COMMENTARY: By David Robie

Timor-Leste, the youngest independent nation and the most fledgling press in the Asia-Pacific, has finally shown how it’s done — with a big lesson for Pacific island neighbours.

Tackle the Chinese media gatekeepers and creeping authoritarianism threatening journalism in the region at the top.

In Dili on the final day of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s grand Pacific tour to score a multitude of agreements and deals — although falling short of winning its Pacific region-wide security pact for the moment — newly elected (for the second time) President José Ramos-Horta won a major concession.

Enough of this paranoid secrecy and contemptuous attitude towards the local – and international – media in democratic nations of the region.

Under pressure from the democrat Ramos-Horta, a longstanding friend of a free media, Wang’s entourage caved in and allowed more questions like a real media conference.

Lusa newsagency correspondent in Dili Antonió Sampaio summed up the achievement in the face of the Pacific-wide secrecy alarm in a Facebook post: “After the controversy, the Chinese minister gave in and agreed to speak with journalists. A small victory for the media in Timor-Leste!”

Small victory, big tick

A small victory maybe. But it got a big tick from Timor-Leste Journalists Association president Zevonia Vieira and her colleagues. He thanked President Ramos Horta for his role in ending the ban on local media and protecting the country’s freedom of information.

Media consultant Bob Howarth, a former PNG Post-Courier publisher and longtime adviser to the Timorese media, hailed the pushback against Chinese secrecy, saying the Chinese minister answering three questions — elsewhere in the region only one was allowed and that had to be by an approved Chinese journalist — as a “press freedom breakthrough”.

On the eve of Wang’s visit, Timor-Leste’s Press Council had denounced the restrictions being imposed on journalists before Horta’s intervention.

“In a democratic state like East Timor not being able to have questions is unacceptable,” said president Virgilio Guterres. “There may be limits for extraordinary situations where there can be no coverage, but saying explicitly that there can be no questions is against the principles of press freedom.”

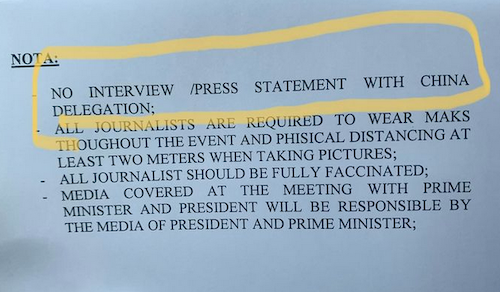

The Chinese delegation justified the decision to ban questions from journalists or to exclude from the agenda any statements with “lack of time” and the “covid-19 pandemic” excuses.

However, Ramos-Horta was also quietly supportive of the Chinese overtures in the region.

According to Sampiaio, when questioned in the media conference about fears in the West about China’s actions in the Pacific, Ramos-Horta said “there is no reason for alarm” and noted that Beijing had always had interests in the region, for example in fishing.

‘A lot of lobbying’

“These Pacific countries have done a lot of lobbying with China to get more support and China is responding to that. These one-off agreements with one country or another, they don’t affect the long-standing interests of countries like Australia and the United States,” he said.

An article by The Guardian’s Pacific Project editor Kate Lyons highlighted China’s authoritarian approach to the media this week, saying “allegations raise press freedom concerns and alarm about the ability of Pacific journalists to do their jobs, particularly as the relationship between the region and China becomes closer.”

But one of the most telling criticisms came from Fiji freelance journalist Lice Movono, whose television crew reporting for the ABC, was deliberately blocked from filming. Pacific Islands Forum officials intervened.

“From the very beginning there was a lot of secrecy, no transparency, no access given,” she told The Guardian.

“I was quite disturbed by what I saw. When you live in Fiji you kind of get used to the militarised nature of the place, but to see the Chinese officials do that was quite disturbing.

“To be a journalist in Fiji is to be worried about imprisonment all the time. Journalism is criminalised. You can be jailed or the company you work for can be fined a crippling amount that can shut down the operation … But to see foreign nationals pushing you back in your own country, that was a different level.”

Media soul-searching

China was moderately successful in signing multiple bilateral agreements with almost a dozen Pacific Island nations during Wang’s visit to the region. The tour began 11 days ago in Solomon Islands — where a secret security pact with China was leaked in March — and since then Wang has met Pacific leaders from Kiribati, Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Niue (virtually), Cook Islands (virtually) and Vanuatu.

However, the repercussions from the visit on the media will lead to soul searching for a long time. Some brief examples of the interaction with Beijing’s authoritarianism:

Solomon Islands: The level of secrecy and selective media overtures surrounding Wang’s meetings with the government sparked the Media Association of the Solomon Islands (MASI) to call on local media to boycott coverage of the visit in protest over the “ridiculous” restrictions.

Samoa: Samoan journalist Lagipoiva Cherelle Jackson criticised the Chinese restrictions on the media with only a five-minute photo-op allowed and no questions or individual interviews. There was also no press briefing before or after Wang’s visit.

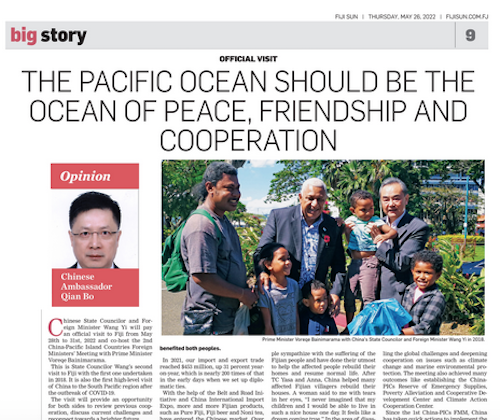

Fiji: No questions were allowed during the brief joint press conference between Wang and Fijian Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama. Local media later reported that, according to Fijian officials, the no-question policy came from the Chinese side.

Examples of local media publishing propaganda were demonstrated by the pro-government Fiji Sun, with a full page “ocean of peace” op-ed written by Chinese Ambassador Qian Bo claiming China’s engagement with Pacific Island countries was “open and transparent”. The Sun followed up with report written by the Chinese embassy in Fiji touting the “great success” of Wang’s visit.

Tonga: Matangi Tonga also published an article by Chinese Ambassador Cao Xiaolin a day before Wang’s visit claiming how “China has never interfered in the internal affairs of [Pacific Island countries]” and would “adhere to openness.”

Global condemnation

The secrecy and media control surrounding Wang’s tour was roundly condemned by the Brussels-based International Federation of Journalists and Paris-based Reporters Without Borders and other media freedom watchdogs.

“The restriction of journalists and media organisations from the Chinese delegation’s visit … sets a worrying precedent for press freedom in the Pacific,” said the IFJ in a statement.

“The IFJ urges the governments of Solomon Islands and China to ensure all journalists are given fair and open access to all press events.”

#RSF condemns #Chinese curb on #reporters during #Pacific island tour #AsiaPacificReport @PNGAttitude @pngfacts @RSF_AsiaPacific #mediafreedom #pressfreedom #ChinaInPacific #WangYi #securitypacthttps://t.co/CGxwNn2O5U pic.twitter.com/XbBIfDIt2u

— David Robie (@DavidRobie) June 3, 2022

Likewise, RSF’s Asia-Pacific director Daniel Bastard said the actions surrounding the events organised by the Chinese delegation with several Pacific island states “clearly contravenes the democratic principles of the region’s countries”.

He added: “We call on officials preparing to meet Wang Yi to resist Chinese pressure by allowing local journalists and international organisations to cover these events, which are of major public interest.”

University of the South Pacific journalism head Associate Professor Shailendra Singh also criticised the Chinese actions, saying “we have two different systems here. China has a different political system — a totalitarian system, and in the Pacific we have a democratic system.”

In Papua New Guinea, the last country to be visited in the Pacific before Timor-Leste, “there appeared to be little resistance” to the authoritarian screen, according to independent journalist Scott Waide, a champion of press freedom in his country.

“There’s not a lot of awareness about the visit,” he admits. “I would have liked to have seen a visible expression of resistance at least of some sort. But from Hagen, where I was this week. I didn’t see much.”

Waide has been training journalists as part of the ABC’s Media for Development Initiative (MDI) programme as a prelude to the PNG’s general election in July.

https://www.abc.net.au/abc-international-development/projects/

The #WangYi Pacific tour reached #Fiji to tight security and a clear message that #China doesn’t welcome foreign media coverage around its officials. Were it not for Pacific media solidarity that is inclusive of ANZ press, today would have been (even more) interesting. #FijiNews pic.twitter.com/C3xwARRGuc

— Lice Movono (@LiceMovono) May 29, 2022

‘Problems to be resolved’

“We have problems that need to be resolved. Over the last month, I’ve tried to impart as much as possible through training workshops on the elections,” he told Pacific Media Watch But there are huge gaps in terms of journalism training. I believe that is a contributor to the lack of obvious pushback over Wang’s visit.”

Reflecting on China’s Pacific tour, Lice Movono, said: “At the time of my interview with The Guardian, I think I was still pretty rattled. Now I think the best way to describe my response is that I feel extremely disturbed.”

She expressed concerns that mostly women journalists from the region noted “but that didn’t get enough traction when other media covered the incident(s) — that China was able to behave that way because the governments of the Pacific allowed it, or in the case of Fiji, preferred it that way.

Movono said that since her criticisms, she had come in for nasty attention by trolls.

“I’m getting some hateful trolling from Chinese twitter accounts – got called a ‘fat pig’ yesterday,” she told Pacific Media Watch.

“Also I’m being accused of lying because some photos have come out of the doorstop we did on the Chinese ambassador here and some have purported that to be an accurate portrayal of Chinese ‘friendliness’ toward media.”

So the pushback from President Ramos-Horta is a welcome sign for media freedom in the region.

Timor-Leste rose to 17th in the 2022 RSF World Press Freedom Index listing of 180 countries — the highest in the Pacific region — while both Fiji and Papua New Guinea fell in the rankings. There are some definite lessons there for media freedom defenders.

Frustrated Pacific journalists hope that there will be a more concerted effort to defend media freedom in the future against creeping authoritarianism.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz