Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Natasha Layton, Senior Research Fellow: Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living Research Centre, Monash University

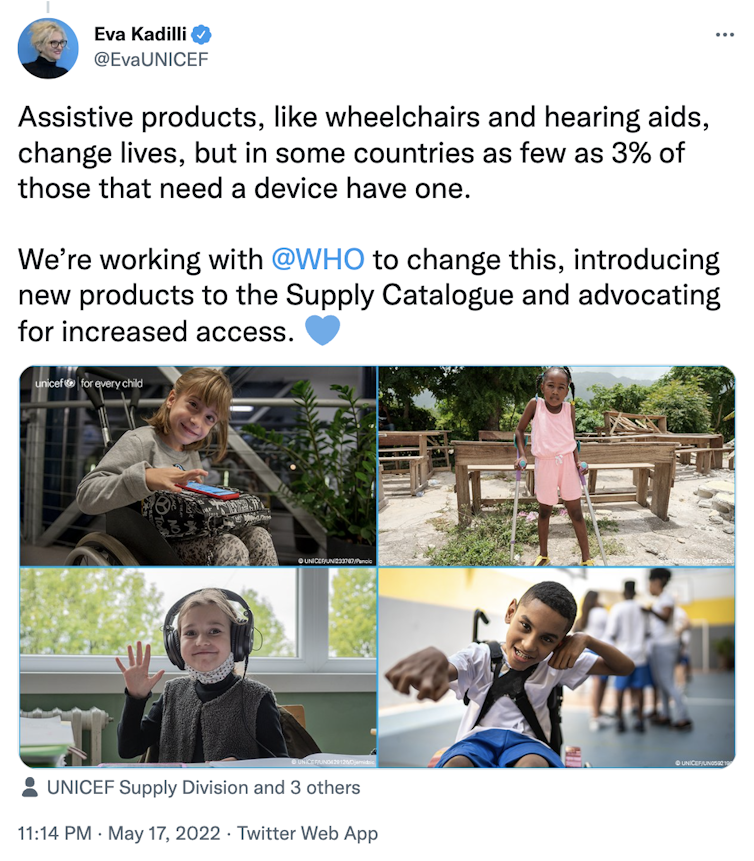

This month, the first ever World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF Global Report on Assistive Technology was released.

The WHO estimates one in three of us will need assistive technology, ranging from glasses to mobility scooters, in our lifetimes. This number is set to grow with an ageing population and the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, which are major causes of disability.

For 2.5 billion people globally and more than two million Australians living with health, disability or age-related conditions, assistive products are vital in daily life. The WHO estimates almost one billion children and adults are denied the assistive technology they need.

The WHO/UNICEF report provides a range of recommendations for policy action that Australia’s new government should consider and learn from.

What is assistive technology?

If you use glasses or screen magnification on your phone, foot orthotics, hiking poles on uneven ground, or a powered mobility scooter to get to the shops, you are using assistive products. Reminder alerts on your mobile phone, smart home and text-to-speech technologies are also in this category.

Then there’s the information, professional recommendations and training needed to fit, troubleshoot, learn to use or maintain your assistive products. Together, these products and services are called “assistive technology”.

The return on investment for assistive technology is around nine times what is spent, because it enables people to work and study, worship and play, control their homes and move around their communities.

How does Australia measure up?

Let’s compare the top recommendations from the Global Report of Assistive Technology with Australian experiences.

1. Improve access to safe, effective and affordable assistive technology

Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) funds support for about 10% of Australians living with disability, including assistive technology products and services.

But outside the NDIS, Australians who need assistive technology often have very restricted access to funding.

They must navigate more than 100 different funding schemes in a “postcode” or eligibility lottery identified by the recent Aged Care Royal Commission as unfair.

2. Invest in research data, evidence-based policy, and innovation

Australia is building a National Disability Data Asset, for safe and secure sharing and linking of data. This will give governments a better understanding of people with disabilities’ life experiences. For now though, there is no detailed data collection on assistive technology use and unmet need in Australia.

On the innovation front, assistive technology that uses artificial intelligence (AI) or changes how a person receives support offers real potential to help people to live how and where they want to. For example, infrared movement sensors in homes – linking to AI – can learn patterns of typical or out of the ordinary events and alert a nominated family member if required, whilst still allowing a person to live on their own.

But Australia needs an ethics framework for the use of AI, including by people with disability, to protect privacy, safety and effectiveness – and more broadly, human rights.

Read more:

Digital inequality: why can I enter your building – but your website shows me the door?

3. Enlarge, diversify and improve workforce capacity

Australia is facing workforce shortages across health, disability and aged care.

The Global Report on Assistive Technology outlines roles for assistive technology users to be peer supporters, alongside expert health teams.

A skilled and diverse workforce is required, and will include both health professionals at the point of need (via telehealth or in person), and training and employment pathways for the assistive technology peer workforce.

4. Develop and invest in enabling environments

Recent Australian National Construction Code reforms propose minimum accessibility in new housing. This would allow people more choice in where they live, and who they live with.

Author provided

However, some states have refused to adopt this voluntary code.

When the NDIS was introduced, government funding for independent assistive technology advice via state-based information and resource centres, called Independent Living Centres (ILCs), was lost. The ILC National Equipment Database remains online, but the few remaining information clearinghouses – including the Centre for Universal Design Australia and the Home Modifications Information Clearinghouse – rely largely on the goodwill of dedicated volunteers to collate information and resources.

5. Include assistive technology in humanitarian responses

Australia is facing ongoing humanitarian crises with fires, floods and a pandemic threatening lives – and livelihoods.

Our research with people who use assistive technology and their families, as well as providers and civil society showed that during the COVID pandemic, the public health response excluded assistive technology services. They were considered “non essential” by government.

In Australia, during the floods, accessible information and disaster preparedness for people who use assistive technology was absent. This meant that, for example, when the lift in the building of a wheelchair user broke, and the building’s intercom was down, there was no way for them to escape or call for help.

Read more:

Homeless and looking for help – why people with disability and their carers fare worse after floods

This information and support gap, and access to safe evacuations, was often filled by local communities. The knowledge of assistive technology users, their families and providers to create more inclusive preparedness plans will be vital for future disasters.

Time for change

Assistive technology is key to a good life for one in ten Australians.

Labor made a pre-election commitment to a major review of disability services in Australia, and inherits potentially transformative Royal Commission recommendations across both ageing and health care.

The WHO and UNICEF Global Report on Assistive Technology provides a roadmap for the incoming government to involve users and their families in change.

![]()

Natasha previously received funding from the World Health Organization for research now published, and referred to in this article. Natasha is affiliated with the Australian Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology Association (ARATA), the national peak body for assistive technology stakeholders, as a Board Member..

Libby Callaway receives funding from the Australian Government’s Department of Social Services. She previously received funding from the World Health Organization for research now published, and referred to in this article. Libby is affiliated with the Australian Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology Association (ARATA), the national peak body for assistive technology stakeholders, as the current Voluntary President of ARATA.

Louise Puli consults to the World Health Organization.

– ref. From glasses to mobility scooters, ‘assistive technology’ isn’t always high-tech. A WHO roadmap could help 2 million Australians get theirs – https://theconversation.com/from-glasses-to-mobility-scooters-assistive-technology-isnt-always-high-tech-a-who-roadmap-could-help-2-million-australians-get-theirs-183529