Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Martin Loosemore, Professor of Construction Management, University of Technology Sydney

With hospitals under strain from COVID-19, we need to safeguard them against another threat set to increase as the world warms.

That threat? Flooding. Many Australian hospitals were built on cheap land near rivers. But as climate change loads the dice in favour of larger floods, areas previously safe may no longer be so. We must plan ahead to ensure patients and healthcare workers are not trapped by floodwaters.

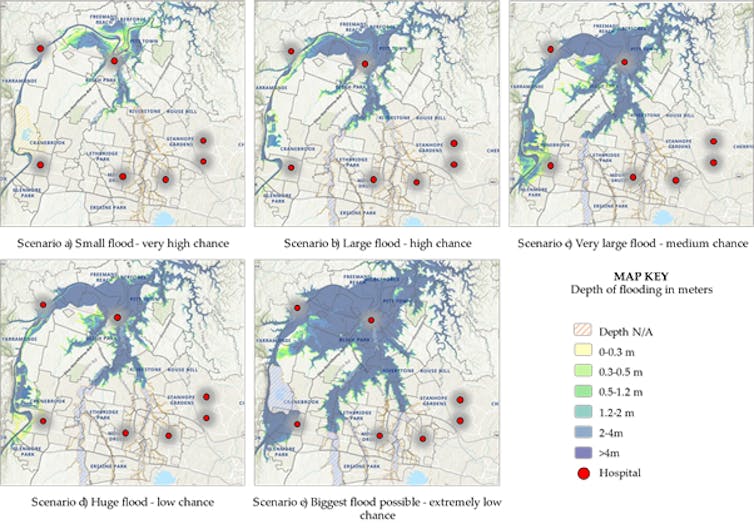

Our new research shows future floods in low-lying areas of Western Sydney are likely to disrupt road networks, preventing safe evacuation of patients. Only last year, this region suffered its worst floods in decades, and more are expected as we enter a flooding cycle. This fast-growing region is rated one of Australia’s highest flooding risks, and hosts a number of healthcare facilities built in flood-prone areas.

The solution? We believe new approaches to mathematical modelling can help decision makers optimise plans for safe evacuation in different flooding scenarios. By cutting evacuation time, we hope these approaches can save lives.

Hospitals were not built to cope with larger floods

Around 80% of Australians live within 50 kilometres of the coast. As a result, many hospitals were built on low-lying land adjacent to seas or rivers. Most were designed without climate change risks in mind.

The major floods brought by La Nina last year, and the catastrophic 2010-2011 Queensland floods, have shown us how exposed many of our cities are to floods. Already in 2022, we have seen large floods up and down the east coast.

Climate change is predicted to bring Australia less rain overall, except for the tropical north. The rain that does fall will be more likely to fall in intense bursts. River flash floods from intense rain events or cyclones will pose an increasing threat to health facilities.

Read more:

Floods are going to get worse: we need to start preparing for them now

Some urban areas are on highly flood-prone areas. For example, the NSW Hawkesbury Nepean flood plan anticipates a flood similar to the infamous 1867 flood would result in around 90,000 people being evacuated.

That’s to say nothing of flooding from the sea. Around Australia, 75 hospitals and health service facilities are within 200 metres of the sea. That puts them at real risk from coastal inundation and erosion by the end of the century, if the seas rise by one metre as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. Hospitals have already been left without power for days due to flooding, while others have been forced to evacuate patients. Only last year, floods up and down the east coast cut roads and forced authorities to find alternatives to hospitals for people unable to get through.

Clearly, this matters. Hospitals play a vital role in creating a disaster-resilient society, and it is critical they can keep operating in disaster situations.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for a better understanding of the threat posed by flooding.

What can we do to prepare?

In our region, very little is known about how we might best evacuate hospitals in the event of a major flood. We simply haven’t done enough research.

What we found in our work is that the issue is extremely complex. Where would patients be evacuated to, for instance? How do you do it safely? Which routes would be safe in a major flood? How would medical staff get to other hospitals?

Evidence from recent floods suggests many hospitals in flooded areas will face major challenges transferring patients and resources to other healthcare facilities.

So what can hospitals do better?

At present, hospital administrators rely heavily on evacuation drills to test and improve emergency evacuation planning. These drills are expensive and disruptive and their effectiveness is difficult to assess.

We have found new approaches to mathematical modelling could greatly assist hospital managers plan for a flood to prevent them becoming disasters.

For example, analysis of Western Sydney’s Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley can visually show how different size flood events would impact on hospitals, healthcare and aged care facilities, as well as roads, bridges and electricity lines.

Author provided

Imagine the Hawksbury-Nepean Valley area floods again like last year. In a scenario where a hospital floods and patients need evacuation, hospital administrators will face a conundrum. Which roads do they send the patients down?

Sophisticated modelling our team is undertaking will let us predict which routes are best, based on the roads most likely to flood, ambulance and staff availability, health needs of patients and the availability of suitable beds and staff in other hospitals. The models allow us to optimise routes for the most urgent patients.

For hospital administrators, the benefit of these models is the ability to glimpse the likeliest scenarios and plan ahead, before the floods happen.

Climate change can supercharge floods, as we are seeing more and more. Decision makers must plan ahead accordingly. Running flood and evacuation simulations now could help save lives in the future.

![]()

Martin Loosemore receives funding from The Australian Research Council

Maziar Yazdani and Mohammad Mojtahedi do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Our hospitals are at greater risk of flooding as the climate changes. We need better evacuation plans. – https://theconversation.com/our-hospitals-are-at-greater-risk-of-flooding-as-the-climate-changes-we-need-better-evacuation-plans-174467