Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Chari Larsson, Senior Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

The spiral of life – the tongue of the cloth

(yan pal ana hmali) – a mutual dialogue 2021

Ramie suspended from metal threads / 500 x 250cm (diam.); installed dimensions variable / Commissioned for APT10 Courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre

Review: Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art

The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art has earned its rightful place in Australia’s cultural calendar for the ambitious scope of its artistic programming, highlighting the diversity and range of artistic practices across the Asia Pacific region. This 10th triennial, ATP10, features 150 artists and collectives from 30 countries.

The curatorial gambit characterising the triennial since its inception in 1993 has always been highly complex: how to give representation to the region’s complexity, without homogenising or flattening cultural differences?

To answer this question, I would point to two interconnected concerns or themes that distinguish APT10: an emphasis on First Nations’ perspectives and a gentle excavation of underexamined or invisible histories.

Cross-cultural conversations

The extraordinary Yolngu/Macassan Project draws attention to the richness of the cultural, social, and spiritual connections between the Macassan sailors from southern Sulawesi in Indonesia and the Yolngu people of north-eastern Arnhem Land.

For hundreds of years, this pre-colonial relationship was based on the Macassan trading tamarind in exchange for sea cucumbers (trepang), until the practice was banned in the early 1900s. The project includes a Yolngu-crafted Macassan sail, bark paintings and pottery shards and underscores the enduring influence of the Macassan’s visits on the Yolngu people.

Courtesy: Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala

Co-curated by Abdi Karya and Diane Moon, the richness of the Yolngu/Macassan Project accentuates the crucial educational role played by APT10: by investing in research and collaboration, meaningful cross-cultural conversations are reignited and brought to the attention of broader audiences.

Another important curatorial collaboration is Between Earth and Sky: Indigenous Art from Taiwan. Co-curated by Paiwan artist Etan Pavavalung and Makatao curator Manray Hsu, eight Indigenous artists from Taiwan work across mediums to retrieve cultural techniques and criticise the corrosive effects of colonisation.

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

For over two decades, Yuma Taru has driven the revival of Atayal weaving and dyeing. Seeking guidance from her grandmother and Tribal Elders, Taru established a collective of local women dedicated to preserving traditional weaving practices and techniques.

The spiral of life – the tongue of the cloth (yan pala na hmali) – a mutual dialogue (2021) is a textile-based installation hung from the ceiling and gives visible representation to the Atayal oral language.

According to the Atayal Elders, words must be akin to the cloth’s softness, so thoughts can be conveyed without injury or damage to the listener.

Ideas of scale

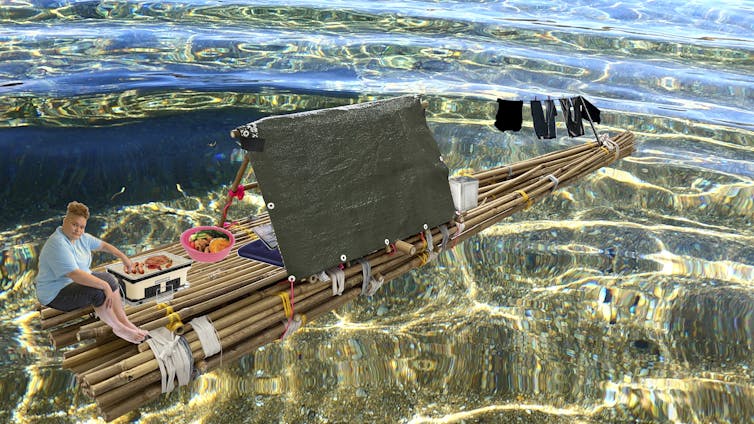

Themes of migration and displacement are taken up by Suva-born, Melbourne raised Salote Tawale. Tawale has exploited the scale of GOMA’s dramatic central gallery space by installing a large bamboo raft No location (2021).

Image courtesy of the artist

The raft was inspired by a traditional Fijian watercraft, bilibili, Tawale remembers seeing in the Fiji Museum in Suva as a child. The vessel becomes a metaphor for moving between cultures and the threat of sea-level rise activated by climate change.

Courtesy: The artist and Portikus, Frankfurt. Photograph: Diana Pfammatter © Alia Farid.

Sitting adjacent is Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid’s large-scale installation In Lieu of What Was (2019). Kuwait’s water consumption is amongst the highest in the world, however, it has no rivers and so Kuwait relies on desalination plants and the importation of water.

Farid’s sand-coloured sculptures stand desolately in the gallery space. It is as if they have been excavated from the future as archival “relics” from when the Gulf region still had access to water.

The impressiveness of scale is also at play in Balinese artist I Made Djirna’s installation Kita (2021). Like strings of enormous beads, hundreds of pumice stones hang from the ceiling, evoking an immersive jungle-like experience.

With its textured and layered cascading pumice stones (traces of the island’s volcanic activity), coconut husks and terracotta masks, the spectator’s attention is focused on the installation’s physical and material presence.

Courtesy: The artist

Curiosity and care

Cambodian artist Svay Sareth spent his childhood in a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodia border during the devastating war-ravaged years of the Khmer Rouge regime (1975-79). Sareth has taken up durational performance as a metaphor for Cambodia’s traumatic and violent history.

In the video work Mon Boulet (2011), Sareth wheeled an enormous 80-kilogram metal ball for approximately 250 kilometres. He had no provisions, prompting chance encounters and interactions for obtaining food, water, and shelter with many people over the course of his six-day journey.

An adjacent cinema series Under the Radar highlights film making from across Asia and the Pacific. Combined with a comprehensive children’s program, APT10 promises to provide a range of experiences drawn from both within and around the region over the summer months ahead.

While the global pandemic grinds on in the background, APT10 feels fresh, forward looking and optimistic. After almost two years of closed and restricted borders, the exhibition delivers a poignant reminder: we are all globally interdependent, however, our local differences demand both our curiosity and care.

APT10 is showing at QAGOMA until April 25 2022.

![]()

Chari Larsson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art shows how our local differences demand curiosity and care – https://theconversation.com/asia-pacific-triennial-of-contemporary-art-shows-how-our-local-differences-demand-curiosity-and-care-173241