Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Gaye Sculthorpe, Curator & Section Head, Oceania, The British Museum

Readers are advised this article contains content relating to violent colonial practices and deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which some may find distressing.

Ancestors of Indigenous Australians are represented in Britain not only by the objects they made. The Ancestral Remains of Aboriginal people still lie in museums or in graves, marked and unmarked.

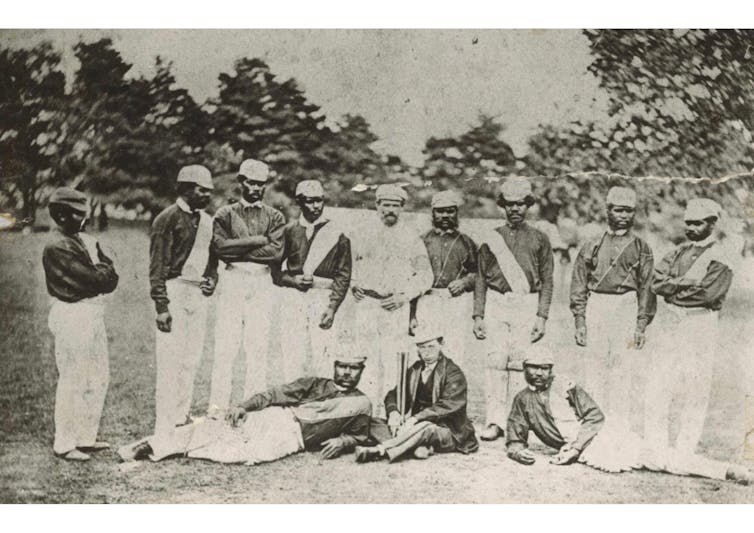

A number of Aboriginal people who travelled to Britain in the late 18th and 19th century died there. These include Yemmerrawanne, who visited with Bennelong in 1793; William Wimmera, whose mother was killed by colonists in northwest Victoria and who was subsequently brought by the Reverend Septimus Lloyd Chase to Reading, where the lad died in 1852; and Bripumyarrimin, “King Cole”, a member of the 1868 Aboriginal cricket team who died in London in the same year.

Wikimedia Commons

Indirect evidence of Aboriginal visitors to Britain and their agency in collecting specimens is also evident in some museum collections. The Natural History Museum, for instance, has plant specimens collected by botanist George Caley in New South Wales. His field collecting was greatly assisted by “Dan”, referring to Daniel Moowattin, an Aboriginal man from the Parramatta region, who came to London with Caley in 1810–11 to work on naturalist Joseph Banks’s collection.

The collecting of Ancestral Remains was a practice that began in the earliest days of the colony in Sydney and continued well into the 20th century. A number of the remains collected were of well-known individuals killed in frontier violence, whose heads became trophies. Throughout most of the 19th century, there was a particular interest in obtaining Tasmanian Aboriginal remains as the people were then believed to be becoming “extinct”.

Both their bones and hair were keenly sought after. While there are large numbers of unidentified Ancestral Remains in British collections, traces of named individuals can be found.

Collectively, they illustrate the violence of the colonial frontier and the wide-ranging medical and other networks of 19th-century collectors reaching from Britain to Australia.

Heads lost and found

Joseph Banks, who visited Australia once as part of Cook’s first voyage, used his extensive contacts in Sydney to seek out both Aboriginal artefacts and Aboriginal human remains. In the early 1790s, Governor Arthur Phillip sent Banks two Aboriginal skulls from “New Holland”, that were destined for Johann Friedrich Blumenbach at the University of Göttingen, Germany.

In ensuing frontier violence, the resistance of Pemulwuy, from the Botany Bay region, resulted in Governor Philip Gidley King issuing an order for his capture in November 1801, and in June 1802 Pemulwuy and another man were shot dead. Pemulwuy’s head was preserved in spirits and was among the “desiderata” sent back by King to Banks in the ship Speedy.

In 1802, the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London noted a gift of “two heads” at that time, although erroneously labelled as coming from Tahiti. Banks’s acquaintance with surgeon John Hunter (whose collections were the foundation of the museum) was likely why the heads arrived at the Royal College of Surgeons.

In August 1818, British artist James Ward, a prolific painter of people and animals, was granted permission by the College of Surgeons to “make Drawings from the two heads in the Museum of Natives of New South Wales”. His journal (October 24 1818) notes: “Begin a study at the College of Surgeons from 2 heads of Botany Bay men”.

Ward’s sketches were exhibited at his house in Newman Street, London, in 1822, and described as:

No. 8. A Native of New South Wales. This order of men is considered as the lowest of human species. The head from which this specimen is taken is preserved in spirits in Surgeon’s College. He was a distinguished chief of a tribe of troublesome marauding predators, a kind of Three-fingered Jack of Botany Bay, which rendered it necessary to put a price upon his head. No. 32 is another view of the same head, with another of the same tribe.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1829, these works appear to be listed for sale again in an auction catalogue from Christie’s. In recent decades, numerous attempts have been made to find Pemulwuy’s remains but without success.

The Royal College of Surgeons was bombed in World War II and the head, which had been preserved in spirit and so perhaps kept only as a skull, may have been destroyed then.

Heads of recently and naturally deceased Aboriginal people were also obtained through institutions’ and surgeons’ interests. John Shinall (c.1809–39) lived much of his life with a white family near Hobart in Tasmania and worked as a farm labourer. After his death his body was mutilated and his severed head preserved in alcohol.

Dr John Frederick Clarke, Inspector General of Hospitals in Hobart, presented it to the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin about 1845–6. It was later photographed and published in 1899 in Henry Ling Roth’s The Aborigines of Tasmania. After tracking it down and seeing it displayed in Dublin in 1985, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre negotiated to have Shinall’s head returned and he arrived home in 1990.

Yagan was a Nyungar man from the Swan River (Perth) region of Western Australia who, like Pemulwuy on the other side of the continent, had resisted the settlers. He was once captured but escaped from custody. In 1833, a price was offered for his head after two settlers were killed following the shooting of a group of his own Nyungar people.

Yagan was subsequently killed and his head was taken to England in the luggage of Lieutenant Robert Dale, who tried to sell it. It was displayed for 12 months by Thomas Pettigrew, a surgeon and antiquarian interested in phrenology. Dale later gave it to the Liverpool Royal Institution, in the town where he lived.

In 1964 it was disposed of, among other remains, as it was badly deteriorated. Following decades of searching by Nyungar people, in 1993 it was identified in an unmarked grave in Liverpool and eventually returned by Aboriginal Elders to WA in 1997.

Richard Wainwright/AAP

A ‘trophy’

The Bunuba people of the Wunaamin Milliwundi Ranges (previously named the King Leopold Ranges) region of northwestern WA are still looking for Jandamarra. In the 1890s, he worked for some time as a tracker for the police but later led a rebellion against European colonists. He was eventually tracked down and killed with help from another Aboriginal man in 1897.

As Bunuba woman June Oscar stated in 2015, the carnage of Aboriginal people at that time devastated Bunuba society. After his death, Jandamarra’s head was taken to England, and was last seen in the 1960s, displayed as a trophy in Greener’s gun factory in Birmingham, which had a museum housing birds, animals and objects relating to shooting.

The factory subsequently relocated and the whereabouts of Jandamarra’s skull today remains unknown.

An anonymous cranium, likely that of a prisoner from the East Kimberley region of WA, was among the collection of 38 Aboriginal objects obtained by Dr James Albert Wetherell of Stokesley and donated to the Dorman Museum in Middlesbrough in 1904. The skull has a handwritten label attached stating

Skull of West Australian aboriginal Native. Observe contracted low, retreating forehead denoting diminished intellectual faculties.

Born in Middlesbrough in 1862, Wetherell trained in medicine at Edinburgh, graduating in 1886. He arrived in WA in 1892 and registered as a doctor, working at Bridgetown and Bunbury before being appointed in June 1892 as a justice of the peace and resident magistrate of the East Kimberley. As Chris Owen has discussed in his book Every Mother’s Son is Guilty, this was an era when police could be disciplined for not shooting Aborigines.

In early 1893, in his capacity as resident magistrate, Wetherell sent out an expedition to punish “savage outlaws” after the attempted spearing of a policeman. He resigned in late 1894 and eventually returned to live in Hull. Newspapers reported that he failed to take care of prisoners in the gaol with many dying, the food he provided being unfit for consumption.

Those released from prison were forced to walk over 200 kilometres home to their country without provisions, some dying on the road. Newspaper accounts relate that Wetherell performed autopsies just outside the gaol in view of the prisoners and kept portions of bodies as curios.

As the other objects in his collection came from the Kimberley region, the cranium likely originated in the Wyndham police district and possibly from an autopsy he carried out. In 2019, the Dorman Museum took steps to initiate its return to the Kimberley.

Fanny Smith’s hair

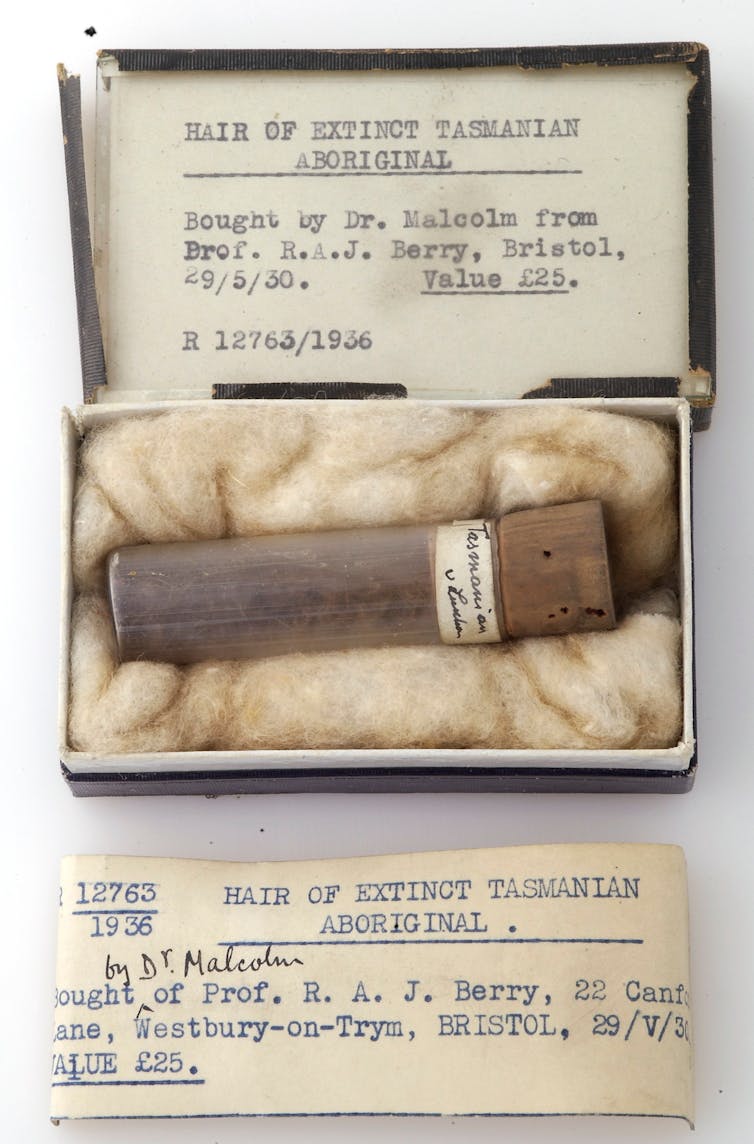

In mid-to late 19th-century Britain, issues of racial origins and human evolution were hotly debated. In this context, not only human remains but also hair samples of different peoples were valued specimens for study and exchange.

Samples from Tasmania were highly sought after, particularly after the death of Trukanini (or “Truganini”) in 1876, who was then often erroneously referred to as “the last Tasmanian”. A hair sample from an unknown Tasmanian was bought by Dr Malcolm of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in London from Dr Richard Berry in Bristol for £25 in 1930.

Wellcome Collection

Read more:

Friday essay: Truganini and the bloody backstory to Victoria’s first public execution

Written in ink on the label of the container is “V Luschan”, indicating an association with Vienna-based doctor and ethnographer Felix von Luschan, who amassed a large collection of human remains.

Trained in Edinburgh, Berry also had a huge collection of Aboriginal Ancestral Remains and while at the University of Melbourne had studied crania robbed from graves in Tasmania, before moving to work in Bristol in 1930.

There he was associated with the eugenics movement, proposing a lethal chamber for “low grade defectives”. The hair sample he sold to the Wellcome Museum has since been returned to Tasmania, as part of a long campaign by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre for the return of Ancestral Remains.

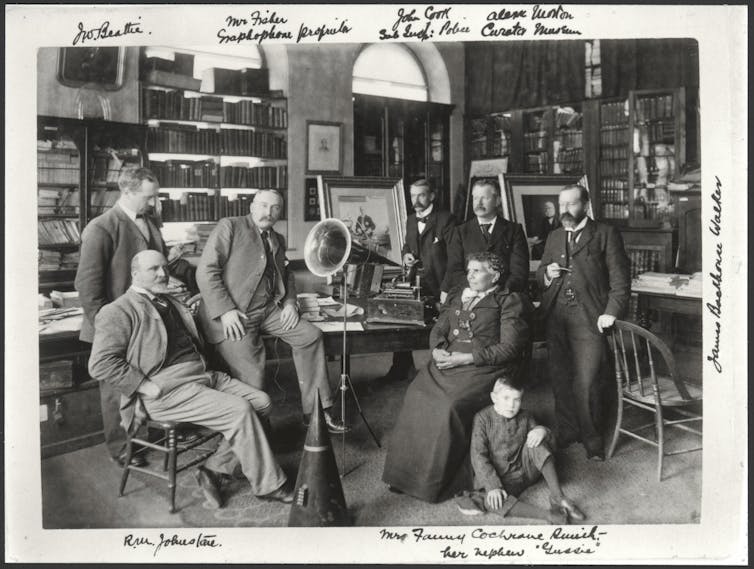

The skeleton and hair of my grandmother’s grandmother, Fanny Smith, were objects of desire for anthropologist and collector Henry Ling Roth of Halifax while she was still alive. In the 1880s and 1890s, it was debated whether Fanny was in fact the “last” Tasmanian Aborigine, and she was particularly noted for her recording of Aboriginal songs on wax cylinders.

Photo: National Library of Australia.

Ling Roth sought help in Tasmania from Quaker James Backhouse Walker and Edinburgh-born photographer and antiquarian James Watt Beattie of Hobart to obtain a photograph of Fanny and a lock of her hair.

Backhouse Walker wrote to Ling Roth on December 20 1891 indicating he “believes Fanny Cochrane Smith is a ‘half-caste’” and advising he might be able to get photographs of her and would ask for a sample of hair, but added, that he “doubts her husband would allow her dissection in the event of her death”.

Fanny lived at a distance from Hobart and there was ongoing difficulty in obtaining the photograph and hair, which was not given up by Fanny until 1894. It was then dispatched by Beattie to Ling Roth.

In 1908, at the request of anatomist Sir William Turner of the University of Edinburgh, Ling Roth sent this sample to him where its physical appearance was discussed along with hair samples from Trukanini and others in a paper concerning “the classification of races based on the colour and characteristics of the hair”.

In the 1990s, following much correspondence between the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre and the Anatomical Museum at the University of Edinburgh, which had told the centre to “desist from further correspondence”, the hair sample was eventually located and returned.

Traces of Australian ‘kings’: ‘King’ McIntyre and ‘King’ Tiger

As Aboriginal societies had important leaders but no “kings” or singular “chiefs”, European settlers and officials sometimes gave breastplates or “king” plates to chosen individuals in their district, as a means of enlisting their help in dealing with other Aboriginal people.

The earliest example noted was given to Bungaree in Sydney in 1815, and by the 1820s they were in common use. Due to the history of collaboration with settlers, such “king” or “queen” plates elicit mixed feelings among Aboriginal people today.

Perhaps surprisingly, few such plates are in British collections. National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh has one given to “Sandy, King of Coringori Australia” and another in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery belonged to “King” McIntyre, a senior man of the Manilla region in northern NSW.

A newspaper account in 1874 suggests the reason McIntyre was given the plate was due to his twice saving the life of Mr Thomas Hoskisson of Bareeba Station. He and his family were consequently “made life pensioners, to the extent of a full ration daily”.

“Tiger, King of Mines Lawn Hills” was a senior man living at or near Lawn Hills Station, a place of copper mining inland from Burketown in northwest Queensland in the early 1900s.

One report suggests he died circa 1930 when he was about 60 to 70 years old by drinking water from a can once containing poison. Subsequently his grave was desecrated and breast plate removed by the station owner of Gregory Downs.

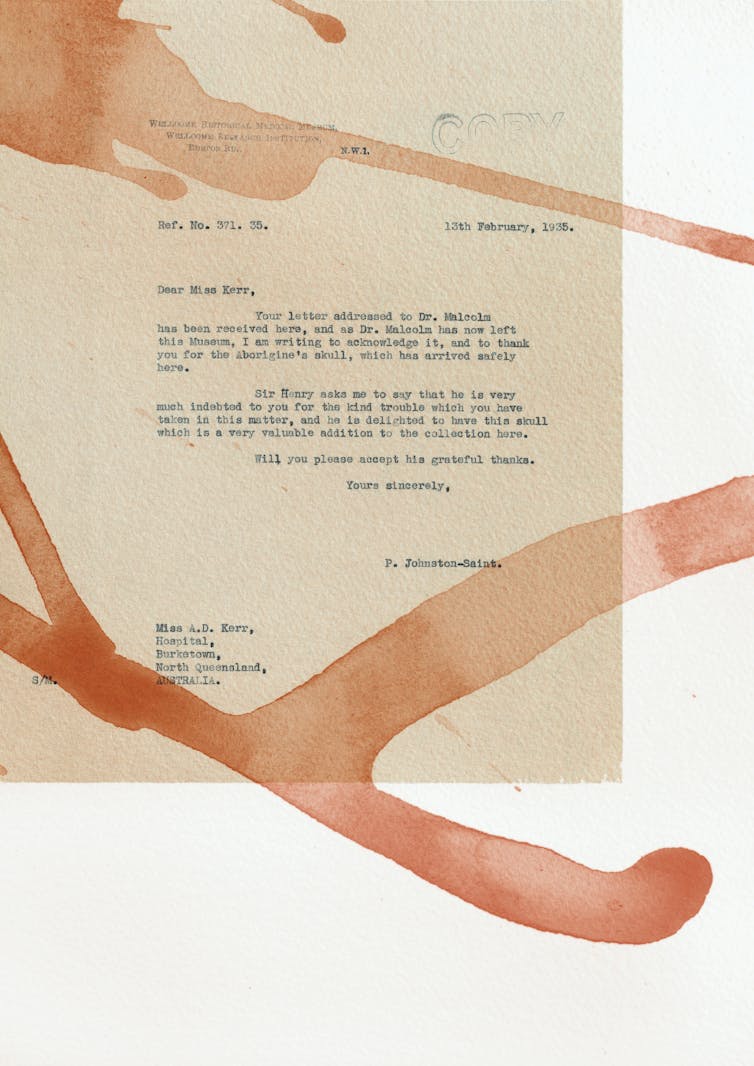

His skull and his king plate were sent to the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in 1935 by Agnes Dorothy Kerr, matron of the Burketown Hospital. Born in England, Kerr had trained as a nurse and worked in New Zealand before serving in the first world war in Egypt and Serbia.

Courtesy Judy Watson, digital image Michael Phillips.

Interested in anatomy from her nursing training she sent a number of human remains from northwest Queensland to Sir Henry Wellcome for his collection in London. In 1936, she received a letter indicating Sir Henry would be very glad to have this plate, making a valuable addition to his collections.

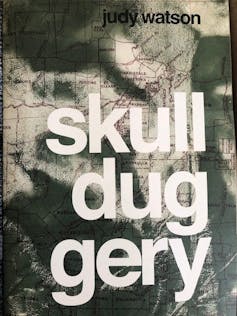

The theft of Tiger’s cranium and breastplate and associated correspondence with Kerr was the inspiration for an artwork and publication titled “skullduggery” by Waanyi artist Judy Watson in 2021, bringing attention to the Ancestral Remains and artefacts still abroad.

Courtesy Judy Watson, digital image Michael Phillips.

The return to Country of Ancestral Remains is a continuing aspiration for Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders across Australia. Some museums in Britain still retain Aboriginal human remains but work to return them is ongoing.

Two cremation ash bundles from Tasmania were returned by the British Museum in 2006; it still retains two modified crania requested by Torres Strait Islanders but refused for return by the museum trustees in 2012.

This work is emotionally difficult for those Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders involved, but programs of repatriation continue, albeit sometimes slowly.

This is an edited extract of an essay published in Ancestors, artefacts, empire: Indigenous Australia in British and Irish Museums, edited by Gaye Sculthorpe, Maria Nugent and Howard Morphy (British Museum Press).

![]()

Gaye Sculthorpe receives research funding from the Australian Research Council through an agreement with the Australian National University and the British Museum. The British Museum is the publisher of the book in which the full version of this article appears.

– ref. Friday essay: Indigenous afterlives in Britain – https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-indigenous-afterlives-in-britain-171479