Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Emily Ross, Lecturer, Curriculum and Pedagogy, University of the Sunshine Coast

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority released a proposed revision of the foundation to year 10 national curriculum for public consultation in April. Since then, the draft national curriculum — the final version of which will be released in 2022 – has caused much controversy. Federal Education Minister Alan Tudge has perhaps been its fiercest critic.

In September 2021, Tudge wrote an opinion piece in The Australian newspaper, saying he will not support the draft in its current form. He noted the revised curriculum, which was meant to simplify the previous one, was “a ridiculously long and unwieldy document”.

The biggest problem, though, was in the draft history curriculum. It gave the impression nothing bad happened before 1788 and almost nothing good has happened since. It downplayed our Western heritage […] It almost erased Christianity from our past, despite it being the single most important influence on our modern development […]

Read more:

10 things every politician should know about history

These comments caused a stir among many historians, who have argued for the importance of critical skills in history. They also stressed being critical is not the same as “hating” Australia. Other controversial topics have included changes in maths content, which some experts have deemed “shallow and faddish”.

So, with all the controversy, some may wonder why we need a national curriculum at all.

The curriculum is like a map

Imagine the Australian Curriculum is a map — a broad picture of all the learning a teacher covers in each year of education for each particular subject. Using the map, teachers charter a course for each unit to ensure the territory is covered across the year and then plan the route they will take with their students.

When using a map to travel a particular route to your destination, you may take a detour along the way. It’s the same when travelling using the curriculum. A student may ask an interesting question, and that might take the class in a different direction for a bit. But that just adds to the journey.

A history of the curriculum

Since Federation in 1901, Australian states and territories have maintained constitutional responsibility for education and have had autonomy for their education agendas. But in 1963 the Commonwealth began funding school education, which came with a desire for more national collaboration.

Since that time, successive Australian politicians and governments have aspired to develop and implement a national curriculum. Their objective was to reduce duplication and enhance consistency across the nation’s various curricula.

The Australian Curriculum we have now is the fourth iteration of a national curriculum, but the first to be effectively implemented. Previous attempts at implementation were met with a range of barriers related to the states’ constitutional responsibility and desire for curriculum autonomy, as well as a lack of clear rationale, purpose and process for curriculum change.

So, the momentum fizzled out. That is, until Kevin Rudd’s 2007 election promise of an education revolution garnered the political support to develop the Australian Curriculum.

The first draft was published by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority in 2010.

What about the states’ curricula?

While the responsibility for developing the curriculum shifted federally, the states retained the autonomy to implement the curriculum. This is because each state and territory has its own senior assessment and tertiary entrance system. Although there have been attempts at an Australian Certificate of Education to mark the end of compulsory schooling, the proposal has never gathered momentum.

The curriculum authority now has the remit to develop the curriculum and the states the responsibility to implement it.

Teachers in Queensland, Tasmania, South Australia, the Northern Territory and the ACT, use the Australian Curriculum as written by the national curriculum authority.

Teachers get the curriculum directly from the website. For these teachers, the Australian Curriculum is like Google Maps. It tells them what to teach.

This is why what is written in the curriculum is of utmost importance. The curriculum authorities in these states and territories exist to support implementation, providing advice on how much of the curriculum teachers are required to implement.

Read more:

A ‘crowded curriculum’? Sure, it may be complex, but so is the world kids must engage with

But Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia, use an intermediary document (or syllabus) in place of the Australian Curriculum. These interpretations, written by their curriculum authorities, repackage the Australian Curriculum. In NSW, for instance, the syllabuses package the content in stages. These each represent two years of schooling (stage 2 is for years 3 and 4, for example).

Occasionally these state packages contain a bit more or less content compared to the Australian Curriculum. For example, the Victorian Curriculum for The Arts has Visual Communication Design as an additional content area.

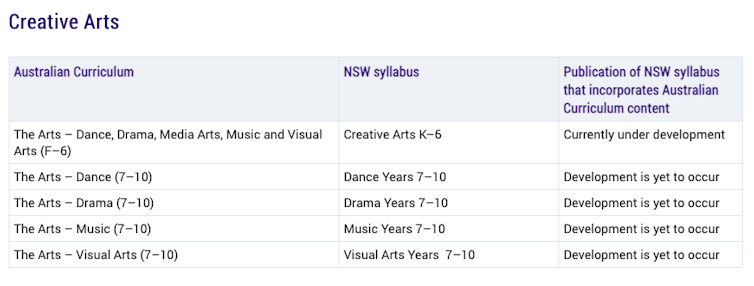

Adding further complexity, some states have not yet updated some subjects (such as languages in Western Australia or the creative arts in NSW) to align with the Australian Curriculum.

NSW Education Standards Authority (screenshot)

Despite these differences, there is still a great degree of alignment in curricula across the states and territories. Prior to the Australian Curriculum some of this was more coincidental than coordinated.

So, why is the curriculum controversial?

Many things influence the curriculum’s development, including the power struggles between federal and state governments and their sometimes differing political ideologies.

The curriculum also needs to be responsive to the needs of today’s students, while preparing them for their future. It must prepare them for jobs that don’t currently exist, with skills we can only imagine, while also ensuring they can navigate the transitions from childhood into adolescence and beyond.

Education Professor Kerry J Kennedy has written curriculum debates are not just an academic argy-bargy over what should or should not be included, but also reflect a “nation’s soul”. It is an insight into what we value. Hence the many heated debates about what is “important” for young people to learn become value laden.

But with a clear rationale we can build the map for Australian teachers to plan their students’ learning journey.

![]()

Emily Ross does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why do Australian states need a national curriculum, and do teachers even use it? – https://theconversation.com/why-do-australian-states-need-a-national-curriculum-and-do-teachers-even-use-it-171745