Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Prudence Gibson, Author and Research Fellow, UNSW

The Eucalyptus tree smells like minty life. Its branches bend and wrap like human arms, its scribbly or papery bark cries out to be touched and it emits a blue, oily haze. It would be hard to find an Australian who hasn’t sat beneath its shady canopy, tugged at its leaves to squeak out a tune, or used its oil to minimise a congested cold.

Eucalyptusdom, a multi-sensory exhibition of museum collection objects and new artworks at Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, is a testament to the utilitarian and cultural life of the tree.

Plant science tells us that trees emit chemicals and gases to communicate with one another, that they spread their roots across astonishing distances and share nutrients via mycelium that spread information to other trees, often from a mother tree to smaller saplings. This adds to cultural and philosophical knowledge that connects with the animism and independent agency of the tree.

Read more:

You don’t have to be barking to think trees are like us

Powerhouse Collection

While this exhibition celebrates human relations with the Eucalyptus, rather than the tree’s own nonhuman life, it does other things such as walking the tightrope towards decolonising the museum’s collection.

This is important work. It refers to (re)telling stories of Aboriginal culture and often means admitting the truth about how museum objects were collected, classified, named and curatorially interpreted, sometimes in culturally insensitive ways.

Zan Wimberley

The exhibition also includes three important Australian cultural figures: the poetic writer Ashley Hay who has written a book called Gum, the great artist Jonathan Jones, and revered Australian architect Richard Lepastrier AO.

Lepastrier co-designed the exhibition and Hay has contributed literary writings to replace exhibition labels, which have long been criticised for their didactic, androcentric and eurocentric tone.

Zan Wimberley

And then there is Jones, who has created yet another installation to stop viewers in their tracks. It’s in a side room of the exhibition, which has the unfortunate effect of seeming like an afterthought, but reverberates with his subtle and finessed (re)presentation of Australian Indigenous history.

On the walls hang eight ink drawings: thick with representations of ceremonial smoke and explained as sentinels. In the centre of the room is a pile of traditional tools, more like a pyre, made from mandang (wood), alongside piles of gum leaves. Jones, a Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist, collaborated with Wiradjuri man, Dr Uncle Stan Grant, to create this work, which includes a sound component.

The pyre is bleached and pale and connects to guardian ancestor Dharramalin, who is central to men’s business. The soundscape presents as the ancestor voice, a roar of thunder and animalistic, aggressive power.

Read more:

Renewable jet fuel could be growing on Australia’s iconic gum trees

Other commissioned Indigenous artworks and soundscapes in this exhibition, include textiles and wearable garments (one made of bark), alongside objects such as jars of eucalyptus sap, tapestry and video portraits.

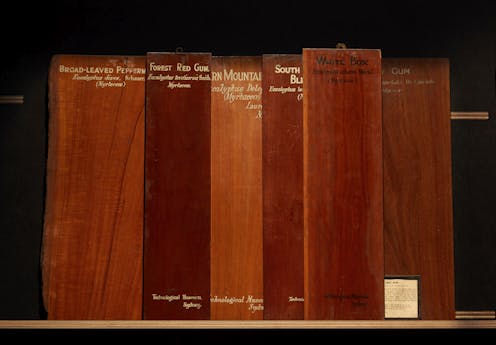

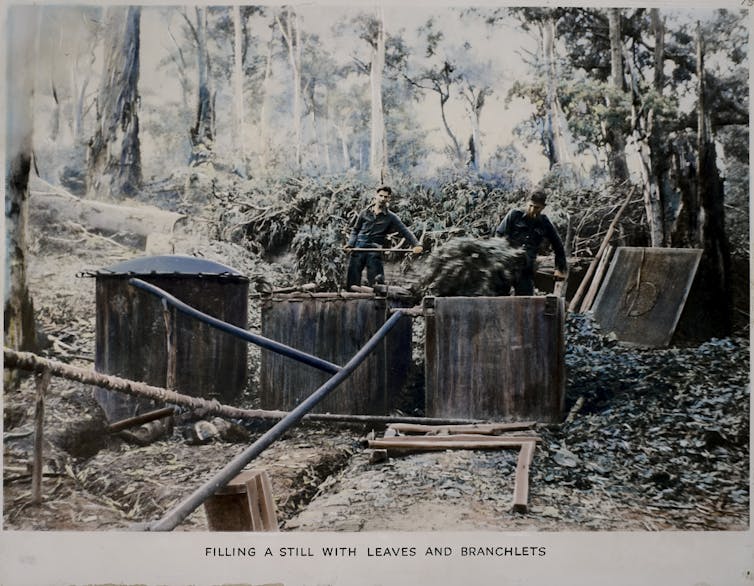

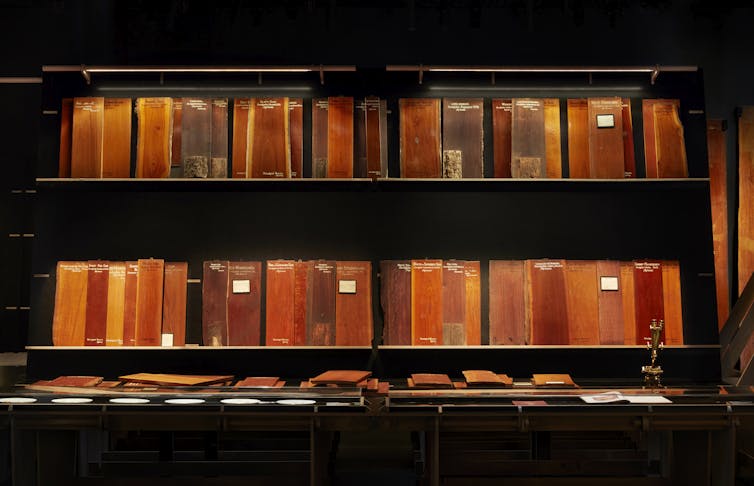

There are also glass plate photographs of settlers felling eucalyptus trees; more than 100 eucalyptus wood specimens from the 1800s collected by the museum and various botanists; painted porcelain plates depicting eucalypts and letters and receipts regarding economic botany from London’s Kew Gardens.

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company Ltd, 1910-14.

Powerhouse Collection

These historically fascinating objects draw a story of settler culture but also lay bare the absence of Indigenous stories therein.

Read more:

Mountain ash has a regal presence: the tallest flowering plant in the world

Decolonising plants

This exhibition presents current and ongoing discussions in “botanical aesthetics”, where plant or tree stories from the settler past sit in (dis)harmony with Indigenous truths and cultural knowledge.

This extends to a wider debate about decolonising plants: understanding the institutional practices that informed and still exist in herbaria, such as following Linnaean naming systems (Latin and common names) without acknowledging Indigenous names.

Zan Wimberley

It reminds audiences of the absence of information regarding the Indigenous botanical collectors who guided the colonial botanists to their rare and bountiful specimens. It refers to the imperial colonial history of malevolent and strident plant collecting that wrought damage to lands and peoples across the world.

Eucalyptusdom is a theatre of colonial collecting but also an introduction to exciting Indigenous artworks. It works as an instruction on how to decolonise plants, in this case the Eucalyptus tree.

While it doesn’t completely escape the subtle dangers of re-colonising the objects and artworks – there is not much dialogue or critique between them – nevertheless, it is a heady and immersive vegetal experience.

Zan Wimberley

Economic botany and colonial botanical curiosity are marked in the exhibition by a cabinet of glass jars containing barks and kinos (a gum-like oozing substance from the tree). These were collected under the direction of Joseph Maiden, director of Sydney’s Royal Botanical Gardens in the late 19th century.

Powerhouse Collection

Read more:

Photos from the field: capturing the grandeur and heartbreak of Tasmania’s giant trees

Such specimens are the perfect reminder of the problems of decolonising collections because they are exquisite objects of aesthetic desire. I don’t know anyone who would want them destroyed or locked away. They feed a human (mostly western) desire to gather, to sort, to order and to name.

The joy of ordering objects is a way of ordering thoughts, for some of us. However, collecting has a violent colonial history and it still feels uncomfortable to view them alongside new Indigenous artworks that work to redress that violence.

This discomfort is perhaps the exhibition’s greatest strength. It reminds those of us who are tree-lovers and/or plant-mad that we have responsibilities to respect the Eucalyptus and to acknowledge that Indigenous people always knew this tree.

Eucalyptusdom is at The Powerhouse until May 2022.

![]()

Prudence Gibson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Oil, wood, bark, exploitation: a new exhibition explores human relations with the Eucalyptus – https://theconversation.com/oil-wood-bark-exploitation-a-new-exhibition-explores-human-relations-with-the-eucalyptus-160268