Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Thomas Moran, PHD Candidate, Monash University

The influence of Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wai on global cinema is difficult to overstate.

Wong emerged from the creative ferment of the Hong Kong film industry of the 1980s which, at its peak, was producing over 200 films a year. He never went to film school but began his career as a scriptwriter, primarily for the action films which would bring Hong Kong cinema to international attention following the release of John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow in 1986.

Today, Wong is primarily renowned as an art film auteur, yet his films traverse genres from melodrama to martial arts. In particular you can see the traces of his past in the Hong Kong film industry with early films As Tears Go By (1988) and Days of Being Wild (1990), riffing on the tropes of gangster cinema.

Read more:

From Bruce Lee to Shang-Chi: a short history of the kung fu film in cinema

His fluid approach to genre is also the result of childhood moviegoing. Wong has described spending time in cinemas with his mother, not differentiating between art films and commercial films. “We just liked to watch the cinema”, he said.

An intertitle in In the Mood for Love (2000) contains the following plaintive reflection:

He remembers those years as though looking through a dusty window pane. The past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

This sentiment crystallises the concerns of Wong’s films: a preoccupation with intimacy, memory and the indelible passage of time as registered in the everyday lives of his unforgettable protagonists.

Guerrilla filmmaking

Wong’s fourth film, Chunking Express (1994) brought him to the attention of Western audiences.

Set in the infamous Chunking Mansions, a crowded 17-floor residential and shopping complex in Kowloon, the film introduced cinephiles to Wong’s universe of love-lorn romantics obsessing over the possibilities of what might have been.

A voiceover by one of the characters observes, “Every day we brush past so many people. People we may never meet or people who may become close friends.”

This dance of chance and fate in a global metropolis underpins the film’s frenetic style.

Shot without a script in an improvisational guerrilla method, the film exemplifies the dazzling camerawork of Wong’s long-term collaborative partner, Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle. This relationship, along with production designer and editor William Chang, has given Wong’s films an unmistakable visual style with slow motion, coloured lens filters and extreme wide angles giving an irrepressible vitality to his melancholic works.

Collaboration is a key feature of Wong’s work. He uses a recurring cast of actors such as Tony Leung, who has appeared in seven of Wong’s films, and other luminaries of Chinese cinema such as Maggie Cheung and Leslie Cheung. They have all delivered career defining performances under Wong’s careful direction.

Read more:

In the mood for Wong: whatever happened to Wong Kar-Wai?

The poetry of everyday life

What has given Wong such a devotional following across the globe is the way he inexorably returns to the poetry of everyday life and the theme of heartbreak.

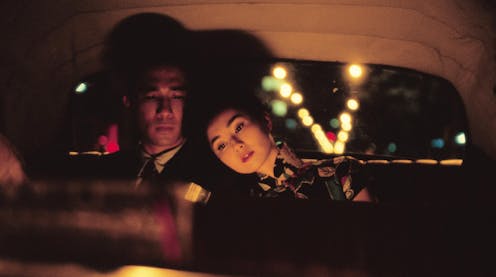

Whether this is the tortured romance between two men stranded in Buenos Aires in Happy Together (1997) or the unconsummated love affair of In The Mood For Love and its sequel, 2046 (2004), Wong’s filmography is an extended meditation on the ordeals of the heart.

His films emphasise character, mood and detail over plot. As he describes it:

Cinema can be the citric scent of a peeled orange, the touch of warm skin through a silk stocking; or simply a darkened space bathed in anticipation.

Wong’s films illustrate the way everyday objects and places are imbued with extraordinary meaning through the power of longing.

This concern with intimate details – the light from an ostensibly kitsch waterfall lamp, the expiry date on a can of tinned pineapples, the way smoke curls upward from a cigarette – give his films their incomparable lyricism and singular capacity to reflect on time’s merciless flow.

History and intimacy

By capturing the fleeting and the ephemeral, Wong’s films act as a powerful form of cultural memory.

This is most obvious in the nostalgic ambience of In the Mood For Love, set in the 1960s, where he had the entire crew eating Shanghainese food popular in 1960s Hong Kong and oversaw the meticulous design of the iconic cheongsam dresses worn by Maggie Cheung.

History is just as present in the films shot in Hong Kong in the 1990s: a place changing so rapidly, many locations had already disappeared by the time shooting had finished.

For Wong, cinema is a way of reflecting on history through the most intimate details. An object may appear minor or inconsequential, but in his films is liable to release a flood of desire.

It is a rare pleasure to see his intoxicating films on the big screen once again for the OzAsia Festival. Returning to his characters is like greeting old friends.

“All my works are really like different episodes of one movie,” the director has revealed. It feels particularly appropriate for his works to be screened together allowing the resonance between the films, with their repeated motifs of clocks, chance encounters and doomed love affairs, to materialise before the viewer.

Wong Kar Wai recently oversaw the restoration of his filmography and seven of these prints are screening at the Mercury Cinema as part of the retrospective Love and Neon during Adelaide’s OzAsia Festival.

![]()

Thomas Moran does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. A cinema of intimacy: the enduring beauty of Wong Kar Wai – https://theconversation.com/a-cinema-of-intimacy-the-enduring-beauty-of-wong-kar-wai-170217