By Charlotte Cook, RNZ News reporter

New Zealand’s Department of Corrections has revealed more details about the LynnMall terrorist’s violent behaviour while he was remanded in prison.

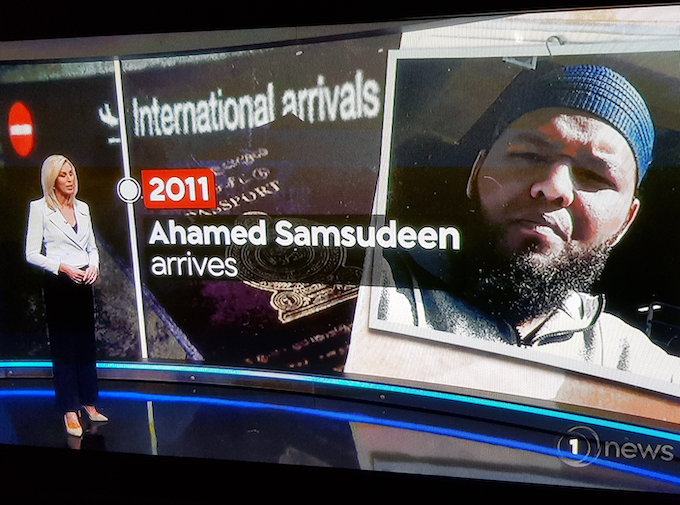

Thirty-two-year-old Ahamed Aathill Mohamed Samsudeen was shot dead by police after stabbing six people inside Countdown LynnMall in West Auckland.

He had spent almost three years on remand in prison and at the time of the attack had only been out for seven weeks.

He had been living at Masjid-e-Bilal in the Auckland suburb of Glen Eden.

The Department of Correction’s National Commissioner Rachel Leota said that while in prison Samsudeen was “non-compliant, with multiple incidents of threats and abuse toward staff”.

This included numerous times when he threw urine and faeces at staff as well as threatening violence and assaulting them.

In one instance at Mt Eden Prison, Corrections said he was unlocked for exercise but began arguing with staff and his behaviour escalated and he hit two officers.

Behaviour escalated again

“When being moved to the management unit his behaviour became escalated again, with threats made toward staff. He then assaulted staff again before force was used and he was secured in a cell in the management unit,” Leota said.

For his last year behind bars Samsudeen was moved to the maximum security Auckland Prison with oversight from the Persons of Extreme Risk Directorate.

This is the same unit set up to manage Christchurch mosque attacker Brenton Tarrant.

The directorate looks after offenders identified as presenting an extreme and ongoing risk of serious harm and/ or having the capability and intent to seriously threaten the safety of prisons and the community.

Because Corrections identified Samsudeen as having “potentially violent extremist views” it got advice from the Countering Violent Extremism forum as to how to best support and rehabilitate the prisoner.

“Attempts were made to provide him with mental health support while he was in prison, however, he refused to engage. He also refused to meet with a Corrections psychologist while in prison.”

The Countering Violent Extremism forum and Corrections then decided to contact the local Muslim community.

Did not engage

The department wanted him to meet with an imam and talk about his spiritual beliefs. This happened twice, but Corrections said he did not engage in a meaningful way.

Prior to Samsudeen’s release from prison the department, police and partner agencies created a plan to keep the community and staff safe from the extreme risk that his violent extremist ideology presented – this included where he might live on release.

The terrorist told Corrections he did not have family, friends or support people able to assist him and would require help, but that he had previously lived at a mosque, although was unwilling to consider it again.

Public housing was not available because of the current demand and Samsudeen eventually said he would consider a mosque.

Leota said Corrections met with police and the Masjid-e-Bilal manager who was told the context around his charges, his risk profile and the conditions he would have when released into the community.

The mosque’s manager told Corrections he would consider it, but wanted to meet Samsudeen first.

The pair met while he was in prison and the address was approved.

.png?1630700403)

Regular communication

During the seven weeks Samsudeen was in the community, Corrections said it had regular communication with the manager at Masjid-e-Bilal and his lawyer.

The department had also started an application to the High Court for strengthened restrictions due to concerns about his escalating risk.

It also looked at charging him for the lack of engagement with both a private and Corrections psychologist, but was told it was not sufficient enough to be considered a breach of his conditions.

Leota said she was confident that Community Corrections staff were using every lawful avenue available to monitor, assess, mitigate, and manage his risk.

“He was a very, very difficult person to manage, and was increasingly openly hostile and abusive toward probation staff.

“Despite this, staff continued to work hard to engage him in his sentence, and attempt to have him participate in treatment and activities aimed at reducing his risk of violence, which he consistently refused.”

Leota said she believed Community Corrections’ contact with him exceeded the minimum level for someone subject to supervision and staff worked exceptionally hard to prevent the potential for serious harm to be caused by this person.

“They, and all of us, will always ask what more could have been done to prevent the horrific offending that occurred on Friday,” Leota said.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz