Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Catherine de Fontenay, Honorary Fellow, Department of Economics, The University of Melbourne

Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock

Until COVID, Australians had a pretty safe assumption that global supply chains could supply more or less whatever they wanted.

And then it became hard to get sanitiser and masks and other kinds of personal protective equipment.

Most of those supply chains were quickly reestablished, but the sudden appearance of vulnerabilities prompted Treasurer Josh Frydenberg to commission the Productivity Commission to prepare a report identifying significant vulnerabilities and ways of dealing with them which I co-authored.

Terms of reference, Productivity Commission Study Report into vulnerable Supply Chains

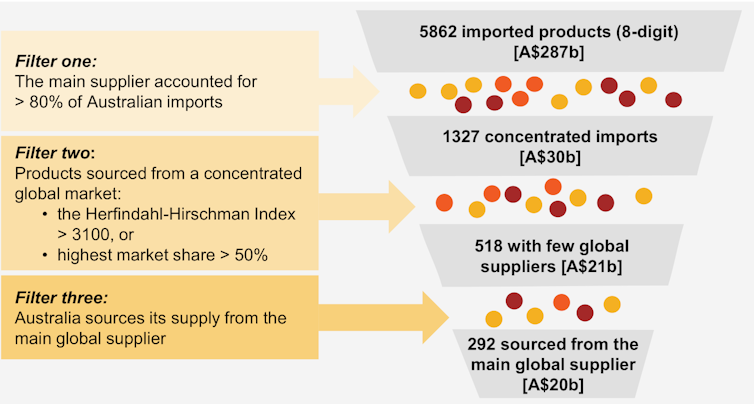

We approached the task with a broad scan of the data. The advantage of a data scan is that it can identify products vulnerable to disruption that experts might have missed.

Our approach was to first identify the products that are vulnerable to supply

chain disruptions and then to identify which of them were used in essential industries. Experts can then determine if it’s possible to replace the product in a crisis.

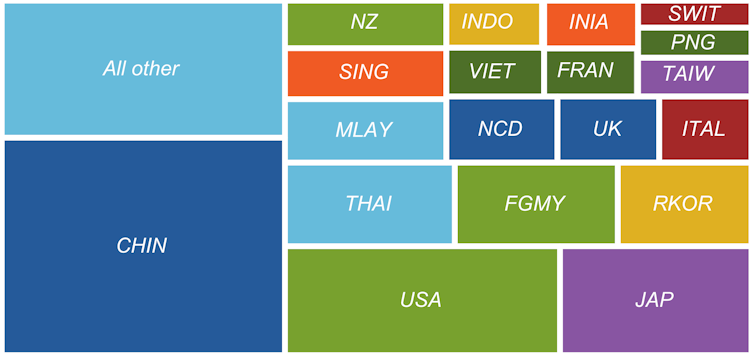

Australia imported 5862 different products from 223 countries in 2016-17. The biggest suppliers were China and the United States. Combined, they accounted for just over one third of the value of goods imported.

Australian imports come from many sources

Productivity Commission

We found that 1327 of the 5862 products (one in five) came from concentrated import markets.

The most concentrated were chemicals, iron and steel, and equipment.

Imports of other products including seafood and some types of clothing were also highly concentrated.

Market concentration creates vulnerability

We considered how markets were likely to respond to a disruption of supply or a spike in demand. As was experienced during the spike in demand for protective equipment, shortages trigger a period of uncertainty during which existing contracts and personal relationships help determine who gets goods first.

But fairly soon after, who gets what gets determined by the prices buyers are willing to pay.

So a product is vulnerable if much of the world supply is concentrated in one country; if that country experiences a natural disaster or other shock, the remaining world supply is very limited, and prices will be astronomical.

A filtering process was used to identify vulnerable imports

Productivity Commission Study Report into vulnerable Supply Chains, August 2021

China is the main supplier of about two thirds of the list of vulnerable imported products, although the main source of supply varies by product.

Many of the imports classified as vulnerable were clearly not critical to the wellbeing of Australians; among them Christmas decorations, swimwear, luxury watches and American peaches.

The essential supplies that were vulnerable included personal protective equipment and certain chemicals.

Onshoring can’t always help

Some commentators and some policymakers have recommended onshoring critical supplies.

A problem with this is that onshore manufacturing could not have prepared us for a ten-fold spike in demand for personal protective equipment unless we produced multiples of what we needed.

Onshore manufacturing of the Pfizer vaccine would still require importing 280 components from 19 countries, some of which are the true source of scarcity according to Pfizer.

The principle outlined in our report is that most of the time governments should be responsible for managing their supply chains (for example in hospitals), and private firms should be responsible for managing theirs.

Read more:

‘Panic-buying’ is the new normal: how supply chains have adapted

The government should intervene in private markets only when the private firm is more tolerant of risk than the nation. The correct response depends on the nature of the risk.

Among the responses possible are measures to encourage firms to build domestic stockpiles, to diversify, to write contracts with contingencies for emergencies, and (in only rare cases) to manufacture domestically.

Income from most exports is safe

Excluding iron ore, only 1.5% of Australia’s exports are at risk of disruption, having no alternative markets.

Iron ore accounts for about 40% of Australia’s goods and services exports to China, and can be thought of a “mutual vulnerability” — China has few other sources of supply for the quantify it needs, and Australia has few other buyers for that quantity.

Oleksiy Mark/Shutterstock

Recent natural stress-tests have been positive.

Products such as coal found alternative markets after China blocked Australian shipments in 2020. By March 2021 the value of coal exports had returned to the level before the disruption.

Wine, also disrupted, is growing an alternative customer base.

On the other hand timber exports, identified as vulnerable, have not returned to previous levels.

While demand for iron ore from China will probably fall, it might be a disservice to the shareholders of BHP or Fortescue to encourage them to diversify into other markets now.

Shareholders concerned about risk can diversify into other shares.

![]()

Catherine de Fontenay is a Commissioner of the Productivity Commission.

– ref. Mid-COVID, our investigation finds few vulnerabilities in Australia’s supply chains – https://theconversation.com/mid-covid-our-investigation-finds-few-vulnerabilities-in-australias-supply-chains-165962