Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University

Shutterstock

Wildlife worldwide is facing a housing crisis. When land is cleared for agriculture, mining, and urbanisation, habitats and natural refuges go with it, such as tree hollows, rock piles and large logs.

The ideal solution is to tackle the threats that cause habitat loss. But some refuges take hundreds of years to recover once destroyed, and some may never recover without help. Tree hollows, for example, can take 180 years to develop.

As a result, conservationists have increasingly looked to human-made solutions as a stopgap. That’s where artificial refuges come in.

If the goal of artificial refuges is to replace lost or degraded habitat, then it is important we have a good understanding of how well they perform. Our new research reviewed artificial refuges worldwide — and we found the science underpinning them is often not up to scratch.

What are artificial refuges?

Artificial refuges provide wildlife places to shelter, breed, hibernate, or nest, helping them survive in disturbed environments, whether degraded forests, deserts or urban and agricultural landscapes.

Ed Reinsel/Shutterstock

You’re probably already familiar with some. Nest boxes for birds and mammals are one example found in many urban and rural areas. They provide a substitute for tree hollows when land is cleared.

Other examples include artificial stone cavities used in Norway to provide places for newts to hibernate in urban and agricultural environments, and artificial bark used in the USA to allow bats to roost in the absence of trees. And in France, artificial burrows provide refuge for lizards in lieu of their favoured rabbit burrows.

AZ Outdoor Photography/Shutterstock

But do we know if they work?

Artificial refuges can be highly effective. In central Europe, for example, nest boxes allowed isolated populations of a colourful bird, the hoopoe, to reconnect — boosting the local genetic diversity.

Still, they are far from a sure thing, having at times fallen short of their promise to provide suitable homes for wildlife.

One study from Catalonia found 42 soprano pipistrelles (a type of bat) had died from dehydration within wooden bat boxes, due to a lack of ventilation and high sun exposure.

Another study from Australia found artificial burrows for the endangered pygmy blue tongue lizard had a design flaw that forced lizards to enter backwards. This increased their risk of predation from snakes and birds.

And the video below from Czech conservation project Birds Online shows a pine marten (a forest-dwelling mammal) and tree sparrow infiltrating next boxes to steal the eggs of Tengmalm’s owls and common starlings.

So why is this happening?

Our research investigated the state of the science regarding artificial refuges worldwide.

We looked at more than 220 studies, and we found they often lacked the rigour to justify their widespread use as a conservation tool. Important factors were often overlooked, such as how temperatures inside artifical refuges compare to natural refuges, and the local abundance of food or predators.

Alarmingly, just under 40% of studies compared artificial refuges to a control, making it impossible to determine the impacts artificial refuges have on the target species, positive or negative.

This is a big problem, because artificial refuges are increasingly incorporated into programs that seek to “offset” habitat destruction. Offsetting involves protecting or creating habitat to compensate for ecological harm caused by land clearing from, for instance, mining or urbanisation.

For example, one project in Australia relied heavily on nest boxes to offset the loss of old, hollow-bearing trees.

But a scientific review of the project showed it to be a failure, due to low rates of uptake by target species (such as the superb parrot) and the rapid deterioration of the nest boxes from falling trees.

Read more:

The plan to protect wildlife displaced by the Hume Highway has failed

The future of artificial refuges

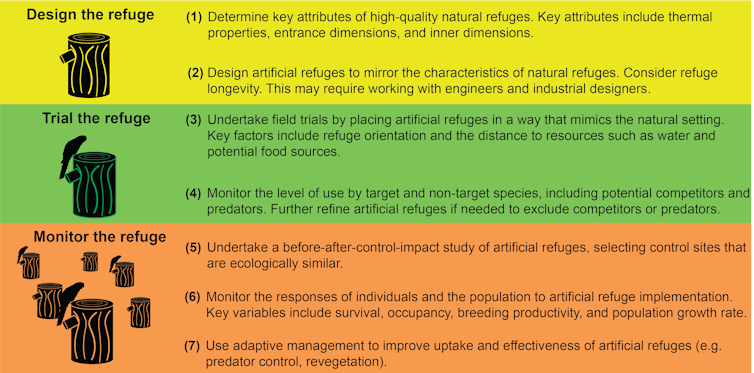

There is little doubt artificial refuges will continue to play a role in confronting Earth’s biodiversity crisis, but their limitations need to be recognised, and the science underpinning them must improve. Our new review points out areas of improvement that spans design, implementation, and monitoring, so take a look if you’re involved in these sorts of projects.

We also urge for more partnerships between ecologists, engineers, designers and the broader community. This is because interdisciplinary collaboration brings together different ways of thinking and helps to shed new light on complex problems.

Author provided

It’s clear improving the science around artificial refuges is well worth the investment, as they can give struggling wildlife worldwide a fighting chance against further habitat destruction and climate change.

Read more:

To save these threatened seahorses, we built them 5-star underwater hotels

![]()

Darcy Watchorn receives funding from the Hermon Slade Foundation, Parks Victoria, the Conservation and Wildlife Research Trust, the Ecological Society of Australia, the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council, and the Geelong Naturalists Field Club. He is a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and the Society for Conservation Biology Oceania.

Dale Nimmo receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, the World Wildlife Fund, Consolidated Minerals, the Hermon Slade Foundation, and the National Environmental Science Program (Threatened Species Hub)

Mitchell Cowan receives funding from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, and Consolidated Minerals.

Tim Doherty receives funding from the Australian Research Council, Hermon Slade Foundation, NSW Environmental Trust, Australian Academy of Science and WWF Australia. He is Chair of the Policy Committee for the Society for Conservation Biology Oceania and a member of the Ecological Society of Australia.

– ref. Artificial refuges are a popular stopgap for habitat destruction, but the science isn’t up to scratch – https://theconversation.com/artificial-refuges-are-a-popular-stopgap-for-habitat-destruction-but-the-science-isnt-up-to-scratch-164401