Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Yasmine Musharbash, Senior Lecturer and Head of Anthropology, Australian National University

Anya Wotton, ANU

The monsters we are familiar with from books, films and TV have long been analysed by scholars as metaphors capturing what ails society. Think of how different types of zombies stand for fears about racial tensions, nuclear destruction, rampant capitalism, contagion, migration and so forth.

The monsters that haunt people off the screen or pages of a book can be found anywhere. All societies and cultures have concepts of, and often deep beliefs in, monsters. In the USA, religious scholars found that in “a strictly numerical sense, people who do not believe in anything paranormal are the odd people out”.

Indigenous Australia is rich in monsters. Some exist in both the realm of stories and in people’s daily lives. One such example are Hairypeople. Much stronger and hairier than humans, it is believed that, since time immemorial, they have lived their lives alongside Indigenous Australians.

Curiosity and intimacy

They made their TV debut as Hairies in the TV series Cleverman (2016-17). In the series, Hairies come into the dystopian city, where they are hunted down, institutionalised, incarcerated and tortured (much like Indigenous people were in the past).

Read more:

Shedding the ‘victim narrative’ for tales of magic, myth and superhero pride

The Hairies are wonderful examples of what anthropologist Faye Ginsburg calls the “Indigenous uncanny”. She contrasts this with the uncanny Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, associated with fear. The Indigenous uncanny, she says,

is characterised by a different register […] shaped by a kind of curiosity about and intimacy with the other side.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), Screen Australia, Screen NSW

Hairypeople are one of the few pan-Australian monsters. It seems they are known in one guise or another and under one or another name across the continent. (Yowie and Yahoo are two of the better known names).

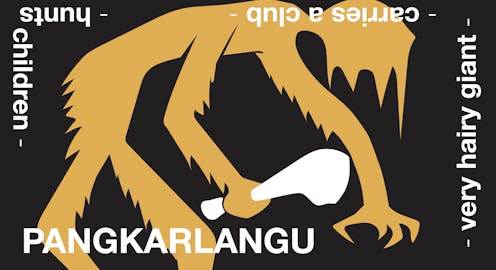

In central Australia’s Tanami Desert, the traditional lands of Warlpiri people, Hairypeople are known as Pangkarlangu. Much like the Hairies in Cleverman, and in ways not dissimilar to zombies in movies, Pangkarlangu in the Tanami Desert are expressive of social concerns — across both time and space.

In the past, and in myths and songs, Pangkarlangu were understood as human-like but uncivilised. They did not perform ceremonies nor bury their dead. Worst of all, they were cannibals known to hunt and eat other monsters, other Pangkarlangu and humans, especially children.

Changed lives

Strikingly, as the lives of Warlpiri people changed with colonisation, so too did the lives of Pangkarlangu.

To give but one example: in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Warlpiri people were confined to a number of settlements close to (but not in) the Tanami Desert. One was called Lajamanu (back then Hooker Creek) in the northwest.

About 450 kilometres as the crow flies to the southeast, another was called Yuendumu.

Harper Collins

Not only is there a vast distance between the two Warlpiri communities, but Lajamanu is on Gurindji country and Yuendumu is on Anmatyere country. This means the inhabitants of each respective community formed close relationships with different peoples and languages.

These new differences were amplified further by Lajamanu orientating towards Katherine and Darwin, in the Top End of the NT, as service centres and Yuendumu towards Alice Springs, in central Australia.

At Lajamanu, as academic Christine Nicholls reports, Pangkarlangu continued to be talked about, they were painted in art, and they were regularly sighted when people went hunting or camping out bush. She describes one group of Warlpiri people “almost stumbling upon” an “an entire family of Pangkarlangu sitting in a circle on the ground having a picnic”. Pangkarlangu, she reports, “seem to be becoming increasingly domesticated, acting a little more like ‘whitefellas’.”

At Yuendumu, on the other hand, for a while at least, they faded into the realm of stories. Until 2013, that is, when a family of Pangkarlangu (a father, a mother and a child) were observed by members of the community — from a distance and over the course of a few days — to be making their way from the southeast towards Yuendumu and then into the Tanami Desert.

A refaunation?

A pervasive way to interpret this event was suggested to me by my Warlpiri friend Kumanjayi Napangardi. She understood the reemergence of the Pangkarlangu from the direction of Alice Springs, and beyond that, the Eastern seaboard, as a kind of refaunation — mirroring the reintroduction of locally extinct species from elsewhere.

Yuendumu is located adjacent to Possum Dreaming (ancestrally linking it to both possums the species and possum ancestors) but possums have been extinct there for decades. Warlpiri people now only encounter possums when they travel to the urban centres of southeastern Australia.

Near Yuendumu, on Warlpiri land, lies Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, a refuge for threatened mammals, including Mala (rufous hare wallaby) from New South Wales. Central Australia not only experiences one of the highest rates of mammalian extinctions — it also is home to a booming refaunation industry. The industry employs rangers, ecologists, biologists and others in caring for, observing and protecting threatened species before releasing them back into the wild.

Given this, why wouldn’t a formerly extinct monster return?

The phenomena of the Pangkarlangu at Lajamanu and at Yuendumu show us the monster heralds change as well as changing itself.

![]()

Yasmine Musharbash received funding from the Australian Research Council (FT130100415)

– ref. Same monster, different meanings: how Indigenous ideas about the Pangkarlangu Hairypeople have changed – https://theconversation.com/same-monster-different-meanings-how-indigenous-ideas-about-the-pangkarlangu-hairypeople-have-changed-160004