Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Stephen Duckett, Director, Health Program, Grattan Institute

Australia’s vaccine rollout started just over four months ago. It has not gone well, to put it mildly. To date, only 24% of the population have had at least one dose of a vaccine, and nearly 5% – 1.2 million people – have been fully vaccinated.

This rate is far too slow. The United Kingdom and the United States are showing that effective mass vaccination programs can work, with more than 80% of Brits and 54% of Americans having received their first dose. Australia should be just as ambitious.

The federal government should press the reset button and shift to Rollout 2.0.

Rollout 1.0 was plagued with supply problems – there just wasn’t enough of either vaccine available. But from July, there will be more supply, with about two million Pfizer doses, and half a million Moderna doses available per week from October – more than enough to cover the whole adult population.

With supply looking sorted, the federal government should set a new goal for when all adults will be able to receive full vaccination by.

The government – and its army of rollout consultants – has had months to learn from its mistakes. The actual army has also been called in.

Read more:

Calling in the army for the vaccine rollout and every other emergency shows how ill-prepared we are

The government has no excuse not to have all arrangements in place for an efficient vaccination program when the vaccines begin rolling in.

Three key things need to be done differently to achieve this goal.

1. Fix the logistics

The supply side of Rollout 1.0 was a shemozzle. GPs and state governments had no idea how many doses were going to arrive and when. This was partly due to slow supply of doses from overseas, but mainly due to slow supply from the local producer, CSL.

That should not be a worry under Rollout 2.0.

But Rollout 1.0 was also a distribution nightmare. It was seemingly impossible for anyone to organise to get doses from place A to place B.

There are now fewer anecdotes about distribution disasters than a few months ago, but the government needs to assure the public that the supply chain and distribution networks are working efficiently.

Read more:

How the Pfizer COVID vaccine gets from the freezer into your arm

If I can be notified when my book or beer is due to arrive – and even the driver’s name – then GPs and state vaccine hubs should be able to be notified when their doses are due to arrive.

And it should be as easy for me to book my vaccination online as it is to book a restaurant table or parcel pick-up online, with advance bookings helping to guide where extra doses should be allocated.

2. Widen the channels

Of the Australians who are getting vaccinated, just over half are doing so through GPs and primary care clinics.

If Rollout 2.0 is to make use of the millions of new doses arriving every week, it will need to deliver at least three times as many doses every week as it has been able to achieve so far.

Government planning seems to be putting GPs front and centre of Rollout 2.0 – the same strategy that failed in Rollout 1.0.

Sure, GPs should be invited to step up, but governments should continue to put a focus on mass state-run vaccination hubs that can vaccinate up to 1,400 people every eight hours, compared to GP clinics that can vaccinate only 100 to 300 people in the same time.

Rollout 2.0 needs to increase both the hours existing outlets are available and expand the number of large vaccination hubs. It should also introduce new outlets such as pharmacies.

States should bring vaccines to people, by providing on-site pop-up vaccination centres at major sports events, workplace hubs, universities, major public transport stations, housing commissions, and regional town centres.

When the Pfizer vaccine is approved for people under 16, states should also arrange for vaccinations to be done in schools.

Because more doses will be available within one month, states should no longer stockpile doses to ensure second-dose availability but rely on fewer supplies for this purpose.

A faster rollout will need a bigger workforce. Planning needs to start now on how we should draw on medical, nursing, and pharmacy students to contribute to Rollout 2.0.

3. Tackle vaccine hesitancy

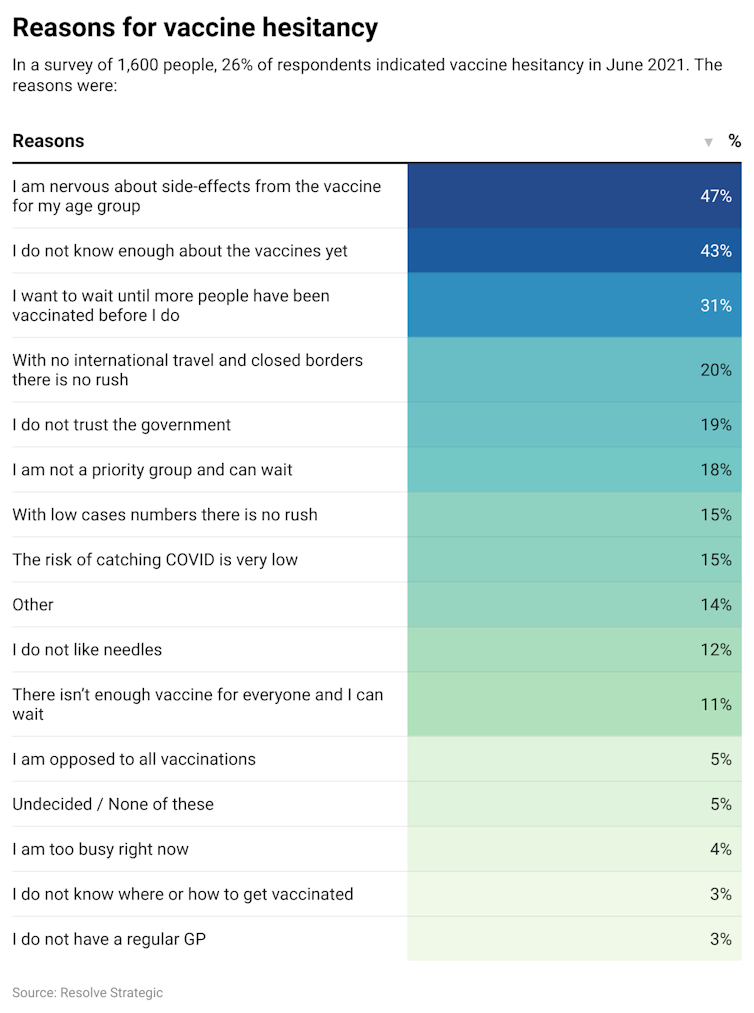

As the government fixes the supply side, it also needs to tackle the demand side – vaccine hesitancy. About 25% of Australian adults say they may not get the jab. The aim should be to change the minds of those who are unsure, rather than focusing on those who are much less willing.

There is a science behind what works in addressing COVID vaccine hesitancy, drawing on previous vaccine campaigns. Government should use it, rather than developing ads that look like the cheapest possible bland offering, which compare poorly to international offerings.

There is not one slick answer, and no one campaign. Different demographics will respond to different messaging. Different reasons for hesitancy will need to be addressed differently.

Ads should be placed at times when target audiences might be watching TV.

A text message campaign could be used, sent to all Australian adults, regardless of their vaccination status, encouraging them to get vaccinated and telling them how, as is done in the UK.

Some campaigns could start now, promoting the benefits of vaccines to individuals and their efficacy. Messaging should also emphasise the collective benefits of high vaccination rates, including protecting the vulnerable and bringing stranded Australians home, just as our collective effort saved lives to date.

Better real-time tracking of vaccine uptake by demographics can be used to develop different messages for different audiences.

The campaigns should go beyond simply pronouncing that all the vaccines are safe and effective. The communication should be ongoing, clear and actionable, address concerns, and de-bunk misunderstandings, without over-reassuring.

Younger people, women, and people who live beyond the inner-city are more likely to be hesitant. Communications should build trust and confidence in government, and not pit groups against each other, which would only increase hesitancy.

The government has over-promised and under-delivered on Rollout 1.0. It needs to push the reset button so that Rollout 2.0 takes Australians to a vaccine-protected future as soon as possible.

![]()

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute’s board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute’s activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website. Stephen Duckett has been partially vaccinated with AstraZeneca.

Anika Stobart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Vaccine Rollout 2.0: Australia needs to do 3 things differently – https://theconversation.com/vaccine-rollout-2-0-australia-needs-to-do-3-things-differently-163479