Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

Review: French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. NGV International

When prospects for overseas travel are bleak, a major exhibition of the work of the French Impressionists is a salvation — a beautiful shining oasis in a somewhat gloomy Australia.

When I lived in Cambridge Massachusetts, across the Charles River from Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston was an unexpected veritable treasure trove. Unexpected in that it is not as well known as some of the museums in New York, London or Paris.

But, with more than 450,000 art objects, it is the 14th largest art museum in the world and is famed for its collection of French Impressionism.

This “neglect” means, of the 100 works at this exhibition, about 80% have never before been seen in this country.

The exhibition sparkles with unexpected treasures including Edouard Manet’s Street singer (c1862), a huge vibrant life-size painting; Claude Monet’s luminous Poppy Field in a hollow near Giverny (1885); Paul Cézanne’s classic Fruit and a jug on a table (c1890–94) and the pulsating Vincent van Gogh, Houses at Auvers (1890).

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Bequest of John T. Spaulding Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

The accessibility of Impressionism

The National Gallery of Victoria’s Winter Masterpieces series of exhibitions commenced in 2004 with the exhibition Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musée d’Orsay. There were then exhibitions of Monet (2013), Degas (2016) and Van Gogh (2017).

Impressionism has certainly been a unifying thread of the Winter Masterpieces series. These four exhibitions have attracted almost a million visitors between them.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Bequest of John T. Spaulding Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

What is it about Impressionism that makes it the most popular art movement amongst the general public? In part, it is because it is such an accessible and undemanding art language.

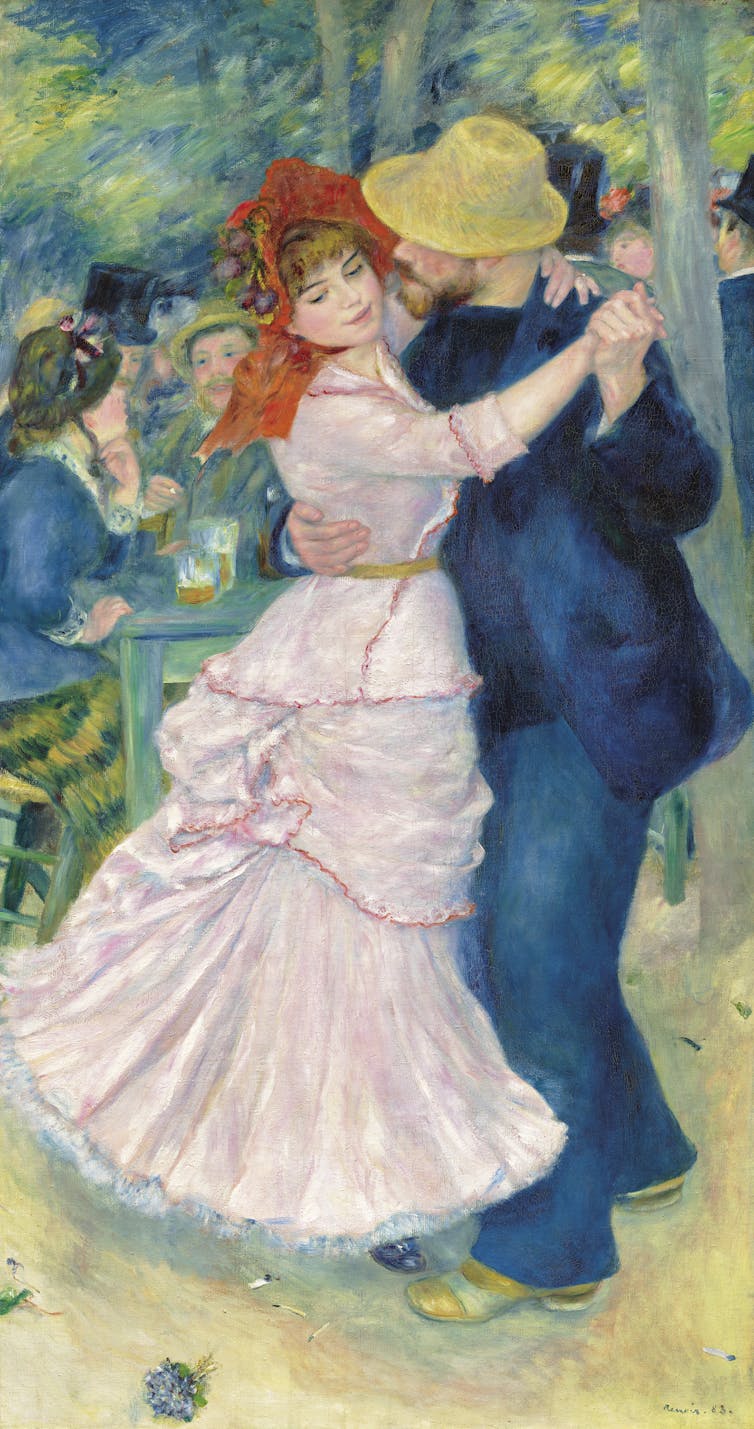

There is no demand made on the viewer to decipher the complexities of mythology — the naked gods in complicated embraces — and the subject matter deals with a reality known and experienced by many in their audience. There is a celebration of a physically accessible countryside; of a hedonistic lifestyle with pretty girls and handsome young men frolicking, flirting and enjoying parties, spending a day at the races or travelling to beauty spots abroad.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Picture Fund Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance at Bougival (1883), an icon image for this exhibition, shows a man eating up the woman in his arms on the dancefloor, while companions sit at tables drinking and sharing the cheer. There is a palpable feeling of a joyous letting go, and celebrating.

You can almost hear the dance music radiating from the picture.

In part, the popularity of Impressionism must lie in the new way of painting with the brighter and more luminous palette, generally the broken, roughly applied brush strokes and the move of the whole colour scheme away from the dark tonal masses to vibrant heightened colour reflexes.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Bequest of David P. Kimball in memory of his wife Clara Bertram Kimball. Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

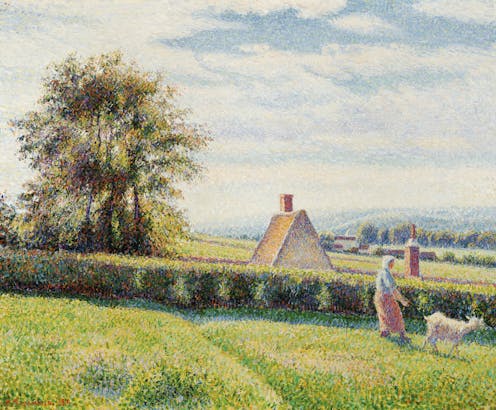

This applies equally to Camille Pissarro’s light and breezy Spring pasture (1889) or the radiating Claude Monet’s Meadow with poplars (c1875). By classical standards, the works appear “unfinished” or impressions of scenes, instead of the carefully composed and compositionally resolved views with their mirror-like finishes.

Berthe Morisot’s White flowers in a bowl (1885) or Monet’s Grand Canal, Venice (1908) sit on the canvas like a sketch breathing with life and light and appear immediate and accessible.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Bequest of John T. Spaulding Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

The iconic and the forgotten

Particularly when Impressionism is interpreted in the very broad sense of the word, as it is in this exhibition to include much of what immediately preceded it, Impressionism attracted some of the best painters over several generations.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston S. A. Denio Collection—Sylvanus Adams Denio Fund and General Income. Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

This show includes some of the greats in realism such as Gustave Courbet, a good selection of Eugène Louis Boudin, the wonderful tonal landscapes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a cross-section of the Barbizon School of landscape painters, right through to Edgar Degas, Alfred Sisley, Monet, van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec.

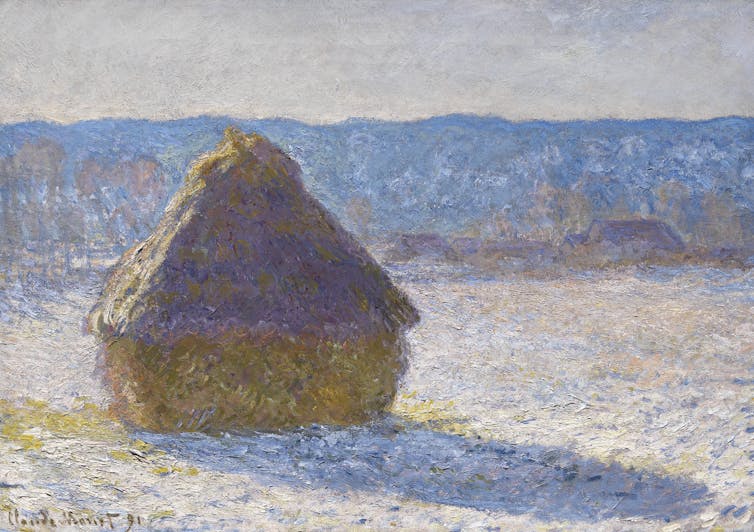

It is a very strong show that combines famous iconic images by some of the great names, such as Monet’s much reproduced and discussed Grainstack (snow effect) (1891) and his water lilies series, with some quirky and puzzlingly neglected works, including Gustave Caillebotte’s Man at his bath (1884).

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Miss Aimée and Miss Rosamond Lamb in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Horatio Appleton Lamb. Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

This Boston Impressionists show, on one hand, caters for a popular audience with a display of some of quintessential “masterpieces” of French Impressionism that will find a ready resonance with any viewer seeking an escapist orgy of sunlight, colour and hedonism.

On the other hand, it is also intended for the very erudite viewer, who can be inducted into the complex nuances and states of Pissarro’s etchings or into Boudin’s profound explorations of colour and mood.

studio 1888. Oil on canvas 55.9 x 46.7 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Bequest of John T. Spaulding Photography © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

Even as COVID clouds gather once more over Australia, French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is almost guaranteed to become a blockbuster exhibition success.

It will assist us in better understanding the Australian Impressionism exhibition presently on show at NGV Australia, and further our love affair with Impressionism.

Read more:

She-Oak and sunlight: ‘the best feelgood show I have seen since COVID’

French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is at NGV International until October 3

![]()

Sasha Grishin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. An orgy of sunlight, colour and hedonism: the French Impressionists are an oasis in a gloomy Australia – https://theconversation.com/an-orgy-of-sunlight-colour-and-hedonism-the-french-impressionists-are-an-oasis-in-a-gloomy-australia-163268