Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Ari Mattes, Lecturer in Communications and Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

Transmission Films

Review: Buckley’s Chance, directed by Tim Brown.

It’s a classic trope of Australian cinema: a foreigner comes here and discovers a wild, rugged place, replete with dangerous and surreal animals and dangerous and weird people.

It’s Walkabout, it’s Razorback, it’s Frog Dreaming. It’s been a common motif throughout the history of Australian cinema and literature and has been discussed in a variety of ways.

In the early 19th century, poet Barron Field fetishised the grotesqueness of Australian flora and fauna. Last century, historian Geoffrey Blainey famously wrote about the “tyranny of distance”, and architect Robin Boyd discussed the “Australian ugliness”.

In the 21st century, apart from a few cinematic outliers — Wolf Creek, Red Dog — it seemed as though Australian culture (if there is such a thing as a national culture) had finally relaxed into itself, freed of the necessity for endless definition and redefinition the enduring “wild and rugged” cliches.

As part of a thriving global culture, Australia could make original, cool films like Upgrade or Snowtown without the continued compulsion to try to sell itself in all its banal glory. Alas, director-producer Tim Brown’s new family schlocker Buckley’s Chance puts this suspicion to rest.

Tried and true and careless

An Australian-Canadian co-production, every cliché of the “foreigner in Australia” narrative is recycled here. The film follows Ridley (Milan Burch) who, following his father’s death, is forced to move with his mum, Gloria (Victoria Hill), from New York City to outback Australia to live with a grandfather, Spencer (a sleepy Bill Nighy), he has never met.

Once in the Great Southern Land, Ridley befriends a dingo he rescues from a barbwire fence with whom he immediately identifies. Ridley is also a lone “fish out of water,” separated from his “pack”, forced on an outback survival adventure when he crosses paths with a couple of menacing goons trying to make Spencer sell his property.

Of course, Ridley triumphs and starts loving Australia.

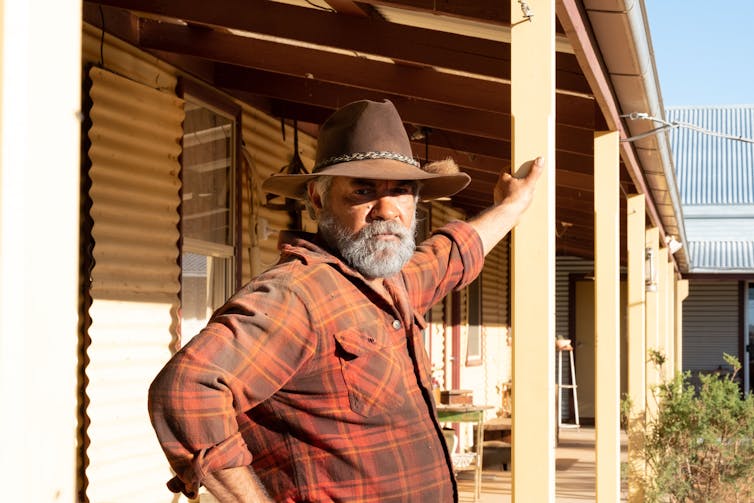

Along the way, he meets a down to earth and wise Indigenous man, Jules (Kelton Pell), who offers appropriately sage advice. He comes across funny sunburned men with very long beards; meat pies eaten by the truckful; and the word “bloody” used ad nauseam.

There are wild animals that are oh so different — goats that run at you, giant snakes — nicknames handed out willy-nilly (“I think it’s an Australian thing,” Ridley’s mum tells him), a town called Budgie’s Knob, an Australian outback that is “very dangerous”.

At one point, Spencer tells Ridley he’ll toss his camera in a “billabong” if he keeps using it, becoming the first Australian, fictional or not, I think I’ve heard use the word outside of a discussion of surfing.

Transmission Films

The problem isn’t the film’s adherence to a tried and true formula, or its absolutely rudimentary narrative, but the flat, careless execution of it all. It all seems so terribly contrived in its attempts to affect us both comedically and dramatically. At one point Ridley’s mum says to him: “No more Mad Maxing around the outback” (!).

The music is melodramatic without being emotionally effective, heavy-handed in its attempts to make the viewer feel something (while at the same time oddly anachronistic, like something from a 1950s B-Western). The performances are either tired (Nighy) or over-anxious (Burch, as a kid, can be forgiven for his poor American accent; the same can’t be said for Hill as his mum).

Transmission Films

It’s hard to pinpoint a single problem. With better music, some of the lameness of the humour or the stilted, soap opera-esque acting may have been diffused. And the ending might have had the emotional impact it warranted.

Watchable … but that’s about it

It’s not all bad; in fact, much of it is watchable (arguably, this makes it less interesting). The footage of the outback is fine — beautiful, panoramic — but so standard in the age of the cheap drone it ceases to be particularly striking.

It’s nice watching a boy and a dingo walking across a giant movie screen, though even the footage of the dingoes is a little disappointing — there’s not enough of it.

One can only imagine the filmmakers are targeting a foreign market (a la Baz Luhrmann’s Australia, which, for all its glossy tedium, is a more skillfully rendered advertisement for Australia than this film). The Australian cliches are too rife, and too on the nose, to imagine any Australian viewer liking this – other than, perhaps, the very young.

There’s even dialogue explaining the origins of the phrase “Buckley’s chance” (it’s obviously very Australian to frequently use this idiomatic gem).

Transmission Films

It’s genuinely difficult to understand how this film was made in the 21st century. In their pandering to mainstream clichés regarding Australianness, the same could be said of Wolf Creek and Red Dog.

But Wolf Creek is a lean, mean film, shocking for its violence, an immersive extravaganza that rightfully has an international reputation as a superb horror film. Red Dog features compellingly dynamic performances from humans and animals alike, an offbeat narrative, and is shot astonishingly well.

As a 1980s-style family exploitation film, Buckley’s Chance is a curious artefact. It is possibly worth watching for its fundamental weirdness. But as a narrative film on its own terms,there’s no reason to see it. And there’s Buckley’s many people will do so.

Buckley’s Chance is in cinemas from today.

![]()

Ari Mattes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Meat pies, desert, bloody dingoes: new Australian film Buckley’s Chance brims with dated cultural cliches – https://theconversation.com/meat-pies-desert-bloody-dingoes-new-australian-film-buckleys-chance-brims-with-dated-cultural-cliches-162858