Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne

In its centenary year, the 2021 Archibald Prize exhibition has been relocated to the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s spacious, second floor. Visitors thus enter the Archibald via the finalists for the Sulman Prize: sometimes regarded as a poor relation to the glamorous and newsworthy portrait prize.

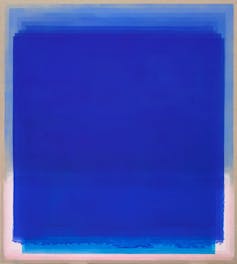

Still, not a few artists have either begun or enhanced their public profile by entering the Sulman, which is judged by one individual rather than the gallery trustees who vote on the Archibald. This year’s Sulman entries are the usual mixed bunch, but Marisa Purcell’s That Time of Day is a witty riff on Yves Klein’s classic blue. Paul Selwood, meanwhile, has pulled off a coup with his finely beaten metal Construction Zone, which is in two dimensions while maintaining the illusion of being 3D.

Some years there is an obvious candidate (or two) for the Archibald Prize. This is not one of those years. It is quite a strong field with many entries either by previous winners, or of them. The subjects range from self-portraits to fellow artists, actors and writers.

There are many portraits of public figures, including Grace Tame, Craig Foster and the biosecurity expert Professor Chandini Raina Macintyre — but no politicians.

If the Archibald reflects who Australians value as subjects to be honoured in some kind of immortality, this is another indication of the reduced standing of our political class.

This being the centenary year, the trustees can be forgiven for showing some sentiment. Peter Wegner’s portrait of artist Guy Warren is not the strongest work in the exhibition, but his subject has the distinction of being both a former Archibald winner and the same age as the prize.

It is, however, livelier than Mira Whale’s portrait of another winning artist, Ben Quilty, who is shown sleeping on a lounge.

In past years, artists have complained the trustees were biased towards large works when selecting their shortlist. There can be no such complaint this year. A delightful wall of almost miniature portraits includes (previous winner) Natasha Bieniek’s study of actor/director Rachel Griffiths and Xeni Kusumitra’s adrift — a portrait of Campbelltown Arts Centre’s Director, Michael Dagostino.

Some previous prize winners have put in very strong entries. Fiona Lowry’s Matthys, of the artist Matthys Gerber under the shower is both light-hearted and insightful.

Joan Ross, a previous Sulman Prize winner, has an unusual but muted self-portrait: Joan as a colonial woman looking at the future.

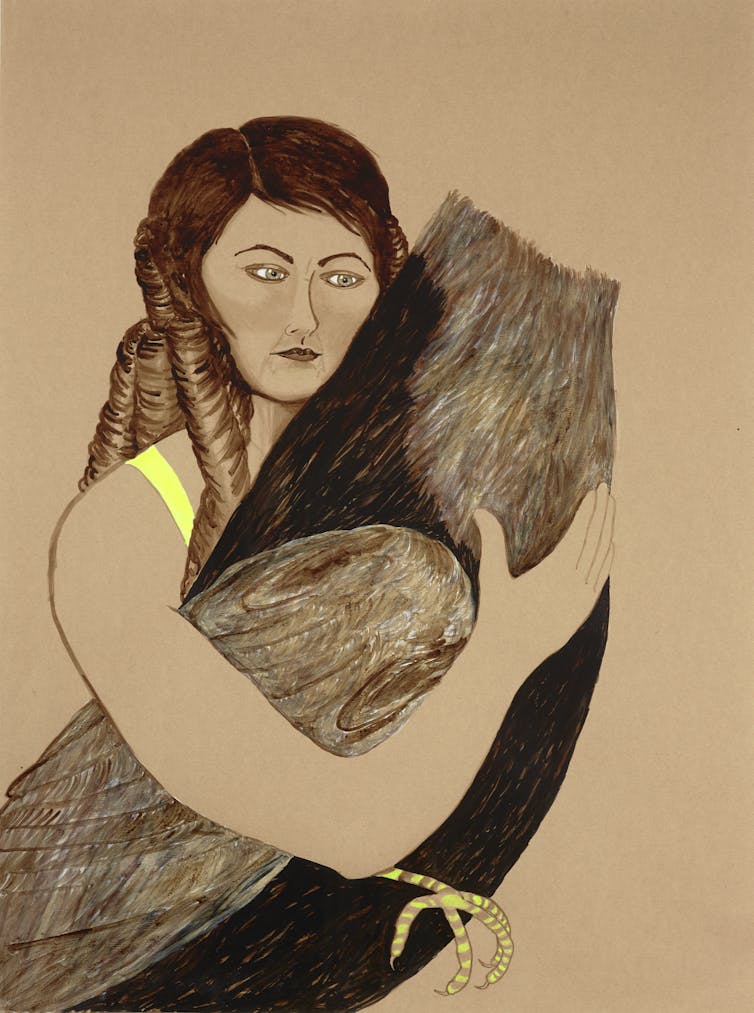

Marikit Santiago, who won the Sulman Prize last year, has entered what must be this year’s most intriguing entry. Filipiniana (self-portrait in collaboration with Maella Santiago Pearl) is a double portrait with two overlapping figures, both in traditional dress.

It is unusual not only in its tribute to older traditions of Philippine art but because the artist has chosen to paint on a large, flattened cardboard box. This has led to the painted surface appearing especially flat, emphasising the decorative nature of the composition.

Perhaps I am biased, but I do find artists’ portraits of fellow artists especially interesting. Jonathan Dalton has taken an unusual approach in his dual study of one of our most gloriously anarchic artists, Ramesh Nithiyendran.

Painted in an academic style far removed from the approach of his subject, the artist is shown as being identical twins, one with a camera scrutinising the viewer.

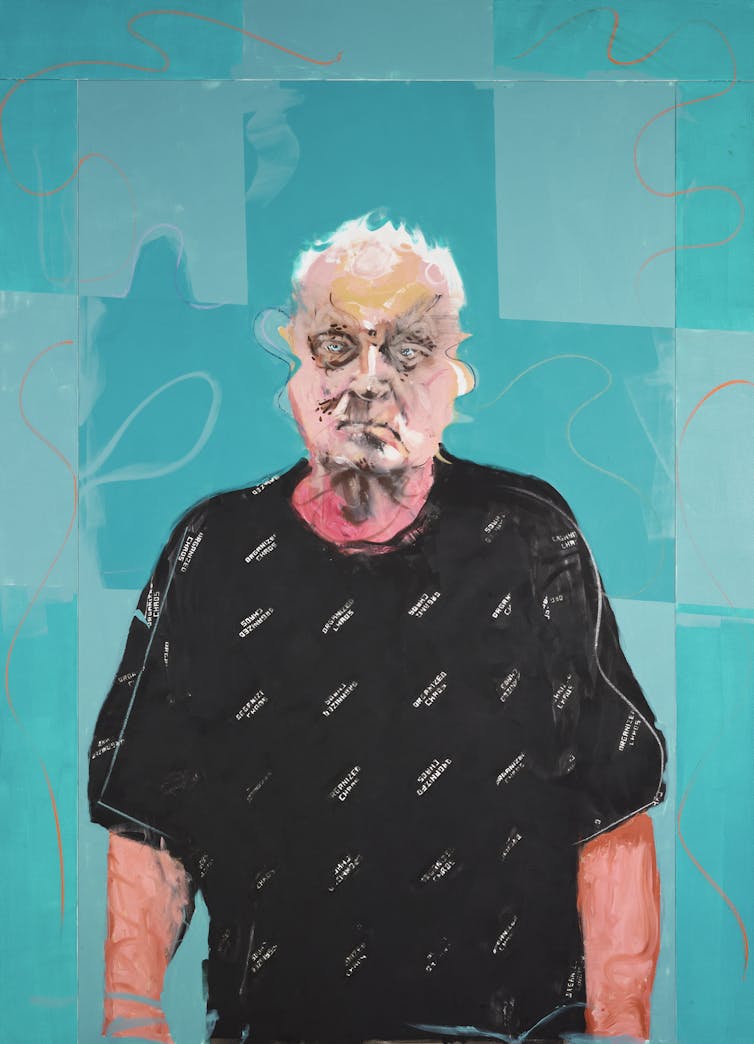

By way of contrast, Benjamin Aitken’s painting of the distinguished artist Gareth Sansom uses the texture of paint to evoke a sense of the artist’s interior life.

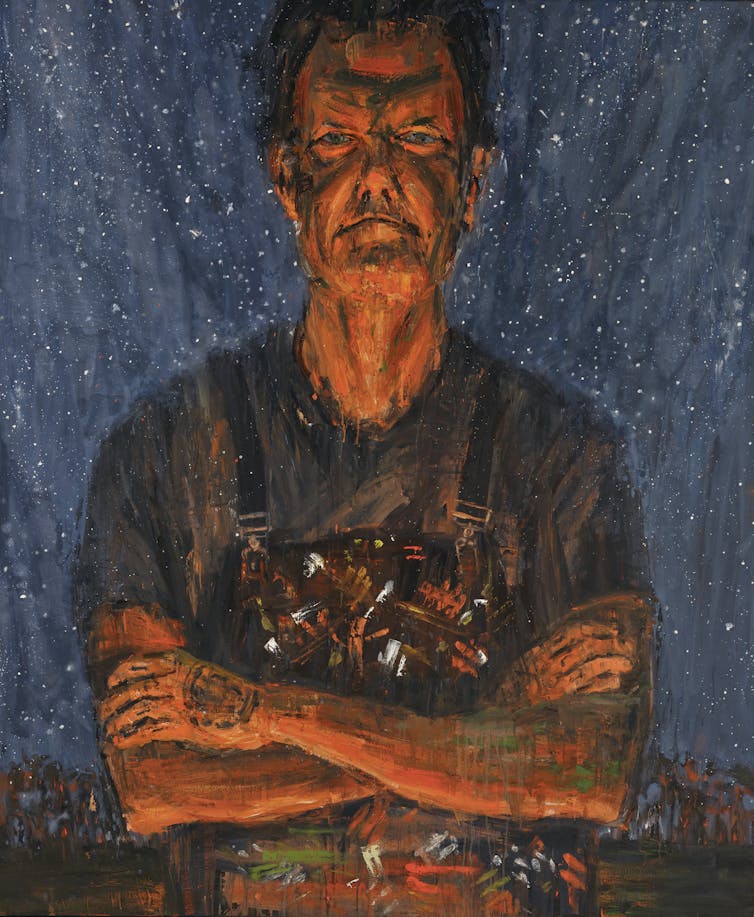

The same intelligent use of paint is seen in one of my personal favourites, Euan Macleod’s portrait of Blak Douglas. Macleod is a former Archibald winner, but to my mind this is a stronger work than the self-portrait awarded the prize in 1999.

Blak Douglas (aka Adam Hill) is a frequent Archibald finalist, sadly not hung this year. Macleod gives a sense of his height, his imposing presence, and the intensity of his persona.

This year’s Packing Room Prize has gone to Kathrin Longhurst’s portrait of singer Kate Ceberano. This is the second time a portrait of Ceberano has won this prize, so clearly the subject is a favourite of the packers.

What is intriguing about this year’s Archibald is not just the absence of politicians, but that many of the public figures celebrated by the art are, like Tame, O’Brien and Foster, openly critical of the behaviour of some of the political class. Perhaps the artists are speaking for many of us.

This year’s Archibald winner will be announced in a week’s time, on June 4.

– ref. From Grace Tame to Craig Foster: distinguished public figures but no politicians in a telling 2021 Archibald shortlist – https://theconversation.com/from-grace-tame-to-craig-foster-distinguished-public-figures-but-no-politicians-in-a-telling-2021-archibald-shortlist-161576