Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui, Adjunct Lecturer, James Cook University

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

The women of the tropical north Queensland frontier were a varied lot and included Melanesian indentured labourers brought to work on sugar cane plantations. Annie Etinside was one of them.

She was brought to Halifax, a small, sleepy town bordering the banks of the Herbert River that was once a thriving port and tramway terminus for the Colonial Sugar Refining Company’s Victoria sugar plantation and mill.

Evidence today of the indentured labourers who once toiled on the plantation is found in small signposts such as one at “The Gardens”, formerly a small Melanesian village on the outskirts of Halifax. Here lived a few families who were not later repatriated to their islands.

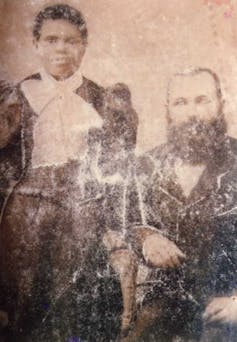

Far fewer women than men were recruited as indentured labourers. In 1906, when forced repatriation of these labourers began, only 14 Melanesian women and 500 men remained on the Herbert. Annie, one of those 14, did not live in The Gardens community. Her life took a very different course.Available records reveal a woman of colour who defied all odds to participate in a predominantly white community. Yet Annie remains an enigma.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

Recruitment

The “frontier” is generally thought of as a masculine space. In part this is because most frontier history has been written by European men, who tended not to notice women beyond their domestic arrangements, if at all. Fleshing out the lives of pioneering frontier women is difficult enough if they are white, let alone for women of colour.

The first Melanesian men were brought to the Herbert River district around 1872; women came about ten years later. Annie appears to have been among them. While some islanders volunteered, others were secured against their own will by deceit and even kidnapping.

They were paid, and at the end of the three-year indenture period could either return to their islands, re-indenture, or work freely in the sugar industry on a set wage. Following the existing record trail leaves many questions unanswered about when Annie arrived and where from.

In the Halifax cemetery, her simple headstone tells us she came from Ureparapara (the third largest island in the Banks group of northern Vanuatu). Yet her death certificate records her as born on “Lambue South Sea Island”. Her marriage certificate records her birth as “Burra Burra South Sea Island”. Neither of these locations can be identified, but the latter may be a corruption of Buka Buka.

A register was kept listing the names of recruited labourers and other details. The only Etinside on this register is a man brought over on November 5, 1888 from Ureparapara. We don’t know if this was Annie, mistakenly recorded as a male.

Details of Annie’s arrival are further muddied by the information provided on her gravestone, marriage and death certificates. According to these, she was born around 1870, so would have arrived in Australia in 1881 as an 11-year-old.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Isabel Flick, the tenacious campaigner who fought segregation in Australia

Marriage

Indentured women were employed both in fields and houses by small farmers, and on plantations. Annie’s obituary, published in the Herbert River Express, says she was first engaged as housemaid to Norwegian sugar cane farmer Johan (John) Ingebright Alm and his wife Antonia, then to an English farmer, Francis Herron and his wife Lucinda.

By 1884, she was housemaid to George Gosling who had migrated from Britain in 1881. George was an overseer of indentured labour gangs, then farmed on leased land and in his own right, turning a piece of land called “Poverty Flat” by locals into a successful farm, Rosedale.

Annie married Gosling in 1898 in a civil ceremony. By this time, she had borne him two children. The children’s birth records are the first bearing the name Etenside (misspelt). At this point, Annie may have begun to feel unsafe. The Aboriginal Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897 had just been passed.

Without an official record to prove she had arrived as an indentured labourer, officials could have identified Annie as Aboriginal. This would have meant restriction of her movements and associations; her children, as mixed race and born out of wedlock, could have been taken from her.

The indentured labour scheme was never meant to permit Melanesian people to settle permanently in Australia. In 1901 the White Australia policy legislated to stop the scheme. From the end of 1906, all Melanesian indentured labourers were to be forcibly deported back to their islands, except for those with exemption tickets.

Marriage offered Annie protection. Rather than social disapproval, it seems to have met with tolerance, even if expressed in a patronising way. One Cairns newspaper described her with tongue in cheek as Gosling’s “little black duck”.

Annie and Gosling had three more children although tragedy struck on January 17, 1905, when Gosling died of malaria at the age of 45. Annie was left with five young children, the youngest only eight days old. On Gosling’s death, Annie was recognised as his lawful widow, inheriting all his estate. The success of his farm can be partly attributed to her. On the Herbert, small farmers depended on wives and children for all field labour, apart from cane harvesting.

Annie had another child in 1907, who she named Robert Gosling. She went on to marry William John Davey on February 17, 1909. But one month after their marriage, she registered the death of little Robert. Davey died on August 30, in the same year. After his death she reverted to using the name Gosling.

Remarkable feats

Despite her “alien” status, Annie integrated herself successfully into the largely white social fabric of Halifax, becoming a respected member of the community at a time of institutionalised racism. She participated in civic life, was registered on the electoral roll and ran a farm.

Her children attended the Halifax State School, her sons farmed and held jobs at the sugar mills (unusual for children of indentured labourers) and her children married Anglo-Australians, Europeans and Asians.

Annie’s were remarkable feats, given the prevailing racial attitudes and prohibitions regarding land ownership, education and constitutional rights. They indicate her determination to be recognised as an accountable, independent and hard-working member of society, regardless of her skin colour.

When Annie died on November 23, 1948 at the recorded age of 78, she was described in the Herbert River Express as a “grand old pioneer”.

– ref. Hidden women of history: Melanesian indentured labourer Annie Etinside, hailed as a Queensland ‘pioneer’ on her death – https://theconversation.com/hidden-women-of-history-melanesian-indentured-labourer-annie-etinside-hailed-as-a-queensland-pioneer-on-her-death-155645