Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Knox Peden, Senior Lecturer in European Enlightenment Studies, The University of Queensland

We have recently seen a spate of books defending the Enlightenment, that period of efflorescence, in 18th-century Europe, which helped shape the modern world.

At the vanguard has been the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, who titled his most recent monument to scientific progress Enlightenment Now. The book earned Bill Gates’s endorsement but was widely criticised by historians since it was not an assessment of the Enlightenment at all, but a compilation of data showing us why life was now better than ever.

Other advocates have been more subtle, stressing that what set the Enlightenment apart from preceding eras was less its confidence in reason per se, than its focus on the secular (as opposed to the sacred) as the space in which happiness ought to be pursued and quite possibly achieved.

Readers might wonder: who could be against this? But Pinker and his allies are pushing back on a tendency to see in the overweening self-confidence of the Enlightenment a blueprint for the horrors of the 20th century. The view is not without merit. The Enlightenment may have given us a new way to think about rights, but it also gave us the atom bomb.

This year marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of a book that contemporaries saw as inaugurating the Enlightenment in France: Montesquieu’s Persian Letters.

Given its exalted status, one would expect to find in Persian Letters an ode to human ingenuity and a confident projection of progress. But its contents are much more surprising — and relevant — than that.

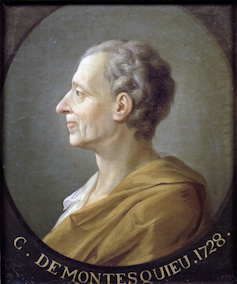

The book’s author, Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu — Montesquieu, for short — was an odd sort, an aristocrat with a sympathy for republics and a voracious intellectual appetite.

Born in 1689, he came of age at a time of French predominance in Europe. A lawyer by training, he began writing during the “Regency”, a period of social dynamism that followed the death in 1715 of Louis XIV, the Sun King, when his great-grandson Louis XV was too young to rule on his own.

A new kind of fiction

In 1721 Montesquieu introduced France to a new kind of fiction, a novel composed entirely of letters, mainly authored by Usbek and Rica, two Persians who have travelled to Paris and delight in reporting their bemusement at its customs. The device allows Montesquieu to make the more familiar features of European life appear idiosyncratic.

The nature of the work also gives Montesquieu ample space to deal with subjects that still divide us: the varieties of government, the extravagances of metaphysical speculation, and the dilemmas of tolerance.

In this regard, we can see Persian Letters as a set of working notes for the book that earned Montesquieu his place among the giants of modern political thought: The Spirit of the Laws, published in 1748. With its case for a “separation of powers” as crucial to a well-functioning republic, this volume inspired Thomas Jefferson and the authors of the US constitution.

Providing a typology of regimes — republics, monarchies, despotisms — and tracing their relationship to material factors from climate to geography, The Spirit of the Laws more or less launched the discipline of political sociology. More prophetic still was the book’s concern for how despotism lies in wait for any regime that sees a loss of civic virtue.

All of this material is dealt with ironically in Persian Letters. The worry about despotism is signalled through what passes for a plot in the book. As Usbek becomes accustomed to Parisian society, he becomes distant from his seraglio (or harem) in Persia.

A revolt ensues in which the women, corrupted by having to live in a degraded state and no longer fearful of their absent authority, stage a bloody uprising. The story ends with a letter from Usbek’s favourite wife Roxane, who is committing suicide, pen in hand.

Constant vigilance

This ghastly conclusion makes for an instructive contrast with the playful tone otherwise permeating the book. Throughout the letters, there is much mirth at Frenchmen who distract themselves with philosophical rumination while their society becomes mired in conflict and sedition.

The irony is to the point; political stability is a matter of constant vigilance, irrespective of the nature of the regime in question.

With his portrayal of the seraglio, a question insists: is Montesquieu indulging in Orientalism, a projection of his Western prejudices on to figures from the East?

Perhaps. And yet Montesquieu never loses sight of the fictional nature of his construction. To see Europe through the eyes of another is to imagine yourself in the position of the other, not to occupy it.

Not coincidentally, this relationship between how we present ourselves and who we are is one of the key themes of the work.

In one of the early letters, Rica recounts the wonder he aroused walking the streets of Paris.

I therefore resolved to set aside my Persian clothing and dress instead as a European, to see whether anything in my appearance would still astonish. From this test, I learnt my true worth: stripped of my exotic finery, I found myself appraised at my real value, and I had good reason to complain of my tailor, through whom I’d lost, in an instant, the attention and esteem of the public.

In reflecting on whether the clothes make the man, Rica suggests the social nature of our identities. In effect, we are as we are seen. But recognising this fact only increases Rica’s desire for public approval.

Elsewhere Usbek remarks that in order to remain powerful a monarch must supply not only necessities, but luxuries. And yet the obsession with luxury — both as a pleasurable experience and opulent display — affects or indeed infects everything, even religion, which is mercilessly pilloried throughout Persian Letters.

The society Montesquieu satirises is one in which moral debates fail to find resolution because agreement is hardly the goal; vindication is. The need for social vindication breeds conflict. We seek out peers who advance what we take to be our interests rather than working with others to discover sites of common interest.

In this aspect, the paint on Usbek and Rica’s portrait of modern life hardly seems dry.

“The reader is urged to note,” Montesquieu wrote in a later edition of Persian Letters, “that the entire charm of the work resides in the constantly recurring contrast between actual reality and the singular, naïve, or strange manner in which reality is perceived”.

The mirror Montesquieu presents to society is one in which its vanities appear in all their absurdity.

With earnestness an increasingly dominant virtue in today’s culture wars, we’d likewise do well to rediscover the charm, indeed the humility, in appreciating the inevitably partial nature of our views.

More than celebrations of science or promises of progress — both of which tend to a self-righteousness foreign to Persian Letters — this seems to be a form of enlightenment we could use, for now.

– ref. Guide to the Classics: Montesquieu’s Persian Letters at 300 — an Enlightenment story that resonates in a time of culture wars – https://theconversation.com/guide-to-the-classics-montesquieus-persian-letters-at-300-an-enlightenment-story-that-resonates-in-a-time-of-culture-wars-160176