By Michael Field of The Pacific Newsroom

In late 1913 one of the most famous men in Britain arrived in Pago Pago.

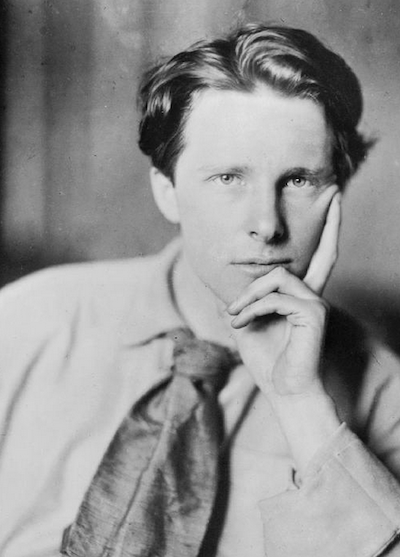

Rupert Brooke, 26, was a literary sensation at the time and was taking an escape from celebrity to explore the South Seas: “I want to walk a thousand miles, and write a thousand plays, and sing a thousand poems, and drink a thousand pots of beer, and kiss a thousand girls – oh, a million things.”

Brooke landed in Pago Pago and quickly moved onto German ruled Āpia.

He marvelled at his accommodation: “I lived in a Sāmoan house (the coolest in the world) with a man and his wife, nine children, ranging from a proud beauty of 18 to a round object of 1 year, a dog, a cat, a proud hysterical hen, and a gaudy scarlet and green parrot, who roved the roof and beams with a wicked eye; choosing a place whence to — twice a day, with humorous precision, on my hat and clothes.

“The Sāmoan girls have extraordinarily beautiful bodies, and walk like goddesses. They’re a lovely brown colour, without any black Melanesian admixture; their necks and shoulders would be the wild envy of any European beauty; and in carriage and face they remind me continually and vividly of my incomparable heartless and ever-loved X.”

The German officials running Sāmoa impressed him saying the two governors had blocked forces that might destroy Sāmoa.

‘Painful operation’

“Dr Schultz, I have been told by old residents of Samoa, was tattooed in the native style, as were certain of his officials. It is reasonable to suppose that this judge, administrator, and collator of Samoan proverbs at least has some ulterior and altruistic purpose in view in undergoing a very painful operation.

“A Samoan who is not tattooed —it extends almost solid from the hips to the knees — appears naked beside one who is; and in no way can the custom be considered as disfiguring.”

English inhabitants had little to complain of other than saying the Germans were “too kind to the natives – an admirable testimonial”.

A Royal Navy gunboat had visited Āpia and were entertained by Sāmoans with music and dance, provided by “an eminent and very charming young princess”. She was a famous beauty with a keen intelligence. Her glorious singing voice made for a successful party.

“The princess led her guests afterwards to the flagstaff. Before anyone could stop her, she leapt onto the pole and raced up the sixty feet of it.”

At the top, she seized the German flag and tore it to pieces.

After visiting Fiji and Auckland, Brooke headed to Tahiti, staying at Mataiea, outside Pape’ete. He met Taatamata: “I think I shall write a book about her – only I fear I’m too fond of her.”

Three poems, no book

“There were three poems, but never a book.

He returned to England, moving toward war.

The Great War broke out in August 1914 and Brooke in September 1914 become a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy Division, an unusual section of the British Army.

He heard that Deutsch-Sāmoa: “is ours,” he wrote, recalling his stay there a year earlier.

“Well, I know a princess who will have had the day of her life. Did they see [Robert Louis] Stevenson’s tomb gleaming high up on the hill, as they made for that passage in the reef….

“They must have landed from boats; and at noon, I see. How hot they got! I know that Āpia noon. Didn’t they rush to the Tivoli bar but I forget, New Zealanders are teetotalers.

“So, perhaps, the Sāmoans gave them the coolest of all drinks, kava; and they scored. And what dances in their honour, that night! but, again, I’m afraid the houla-houla would shock a New Zealander.

Sweetest South Sea songs

“I suppose they left a garrison, and went away. I can very vividly see them steaming out in the evening; and the crowd on shore would be singing them that sweetest and best-known of South Sea songs, which begins, ‘Good-bye, my Flenni’ (‘Friend,’ you’d pronounce it), and goes on in Sāmoan, a very beautiful tongue.

“I hope they’ll rule Sāmoa well.”

That last line was prophetic, given who buried Rupert Brooke.

George Richardson had been born in Britain but in years leading up to war, had been based in New Zealand. In December 1913, then Colonel Richardson sat as New Zealand’s representative on the Imperial General Staff in London.

With war, he became chief of staff of the new Royal Naval Division, an idea of First Sea Lord Winston Churchill to get unneeded sailors into the fighting as infantrymen. It was deployed to Gallipoli.

Rupert Brooke in December 1914 wrote to a friend from a camp in Dorset, that he had dreamt that he was back in Tahiti, where he met a woman who told him that Tahiti lover Taatamata was dead: “Perhaps it was the full moon that made me dream, because of the last full moon at (Tahiti).

“Perhaps it was my evil heart. I think the dream was true.”

A good time

Weeks later, Brooke received a letter from Taatamata, dated 2 May 1914 in which she told of having a good time with Argentinian sailors. She was always thinking of Brooke but wondered if he had already forgotten her.

After she died there were often rumours that Taatamata had a child, a girl, with Brooke and she grew up in Pape’ete.

Brooke wrote The Soldier:

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England.

Two days out from the landings at Gallipoli, on Shakespeare’s birthday (and the same day he died), April 23, Brooke died, the result of an infected mosquito bite.

He was buried on the Aegean island of Skyros.

George Richardson, who after the war would become one of Sāmoa’s worst colonial administrators, was given the job of burying Brooke.

‘I selected his grave on a little knoll under an olive tree and there he lies peacefully today.”

Republished from The Pacific Newsroom with permission.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz