Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Kathryn Daley, Senior Lecturer & Program Manager – Youth Work and Youth Studies. School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, RMIT University

Of the more than 870,000 Australians who lost their jobs in the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis, 332,200 – or 38% – were young Australians aged 15-24.

By June 2020, as the overall unemployment rate hit 7.4%, the youth unemployment rate spiked to 16.4%, with a further 19.7% underemployed (working fewer hours than they wanted).

As of February the overall unemployment rate had fallen to 5.8%, compared with 5.1% in February 2020. The youth unemployment rate meanwhile was 12.9%, compared with 11.5% the year before, and a further 16% were underemployed.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has enthused about there now being “more jobs in the Australian economy than there were before the pandemic”. But that’s true only for those 25 and older: 77,600 more are employed than before the crisis. For those aged 24 and under, 74,100 fewer have jobs.

So clearly the pandemic has hit younger workers the hardest. The reasons for disproportionate impact aren’t complicated. Young people are more likely to work in casual jobs – the first to be excised in hard economic times – and in those sectors most affected by border closures, lockdowns and other measures – retail, hospitality, tourism.Yet the federal government’s policy responses, injecting billions of dollars into the economy to support businesses and employment, have compounded this impact through deliberate yet flawed policy design.

JobKeeper has kept proportionally fewer young people in jobs. Changes allowing withdrawal of superannuation will hurt them more in the longer term. And JobMaker, the program designed specifically to encourage employment of younger workers, has proven a monumental flop.

Shut out of JobKeeper

The centrepiece of the federal government’s support measures was the A$100 billion JobKeeper program, initially paying a subsidy of $750 a week before tapering and finally being axed at the end of March.

The Reserve Bank of Australia estimates JobKeeper payments kept at least 700,000 workers off the dole queue. But to qualify, employees had to have been working for their employer for a minimum of 12 months.

This disproportionately excluded younger workers – being more likely to be recent workforce entrants, to switch jobs more than older workers, and to be in employed in casual or other forms of insecure work.

To illustrate, Australian Bureau of Statistics data from August 2019 shows young people comprised 17% of the workforce yet accounted for 46% of all short-term casual employees.

Of those employed casually, 26.4% of young people had been with their employer for less than 12 months, compared to 6.5% of those aged 25 and over. So one in four young people employed casually were not eligible for JobKeeper, compared with only one in 16 of their older counterparts.

Read more: The budget promises jobs, but does little for workers in the gig economy

Drawing down superannuation

JobKeeper’s design thus pushed proportionally more younger workers on to the dole queue. It also likely contributed to more of them dipping into their superannuation savings under the provisions announced by the federal government in March 2020.

Those provisions allowed Australians affected by the economic crisis to withdraw up to $20,000 from their superannuation accounts (in two rounds of $10,000 each – one last financial year, another this financial year).

The Industry Super Australia estimated about 395,000 people under 35 completely drained their super accounts.

This emptying of accounts is not surprising given the average superannuation balance by age 30 is about $28,000 for men and $23,700 for women.

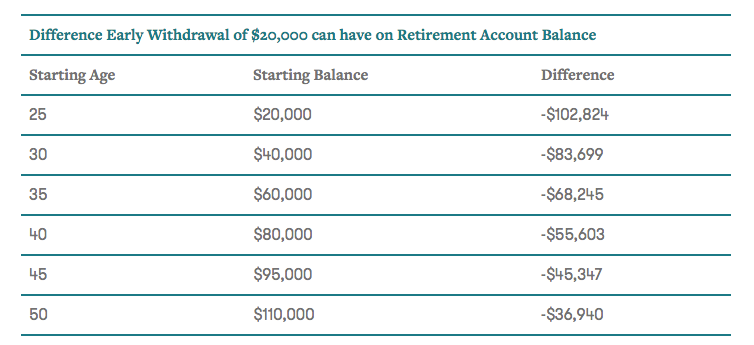

But it means many will have considerably less super to retire on. The long-term cost of a 25 year-old withdrawing $20,000 is more than $100,000, compared with about $37,000 for a 50-year-old, according to estimates by financial comparison site Canstar.

Spend now, lose later

There’s also evidence the design of the super-access scheme has allowed unnecessary withdrawals. While those taking out money have had to declare they need the money to pay for essential items (such as rent or bills), there has been no scrutiny of this prior to approval.

Indeed, according to credit-scoring company Illion about two-thirds of the funds withdrawn this financial year was spent on discretionary items such as clothing, furniture, restaurants and alcohol.

As former prime minister Paul Keating has put it, the government has relied on individuals “ratting their own savings” to buttress its own stimulus spending.

Read more: The economy can’t guarantee a job. It can guarantee a liveable income for other work

More work needed

The one program meant to specifically address youth unemployment, the JobMaker Hiring Credit, has so far proven a failure. Its aim is to incentivise employers to hire job seekers aged 16 to35 with a weekly $200 subsidy, creating 450,000 jobs over two years. But in late March, Treasury officials revealed it had so far led to just 609 hires.

All unemployment is costly for individuals, families and the wider community. But high and long-term youth unemployment can have particularly dire consequences that reverberate for decades. It creates the risk of “scarring”, suppressing an individual’s job and income prospects over their entire life. That ultimately requires the government picking up the tab.

Youth unemployment was already a significant issue prior to the COVID crisis. Now, with younger people hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic impacts, it’s imperative to ensure an entire generation is not permanently disadvantaged.

– ref. JobKeeper and JobMaker have left too many young people on the dole queue – https://theconversation.com/jobkeeper-and-jobmaker-have-left-too-many-young-people-on-the-dole-queue-158294