Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Angela Woollacott, Manning Clark Professor of History, Australian National University

Rage and roar are two words commonly used to describe the events of Monday 15 March, when tens of thousands joined the March4Justice: the emotional rage fuelling the protests; the roar of angry shouting voices raised against the treatment of women.

The anger driving the marches around the nation connects the day’s events to earlier feminist protests in Australia, and by Australian women in London. For well over a century, feminists have been angered by women’s lack of equal rights, their treatment by governments, and issues surrounding sex.

Indeed, for some women this recent protest was just one more in a lifetime of fighting for women’s rights and expressing their anger.

This was especially evident in front of Parliament House in Canberra. The large and energised crowd was diverse: from babies to the elderly; mostly women but many men; Indigenous people and whitefellas; dogs and prams threading among university and school students and those in business attire on their lunch break.

Feminists of the 1970s generation were in abundance, expressing their demands through placards, t-shirts and with their voices. Elizabeth Reid, who served as Women’s Adviser to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam from 1973 to 1975 — making her the first women’s adviser to a head of government anywhere in the world — sat down at the front in a folding chair, a highly-deserved queenly position. Her presence and globally historic role were acknowledged by the speakers.Reid’s friend Biff Ward, a key founder of the Women’s Liberation group in Canberra, was one of the speakers, appearing alongside younger women like Brittany Higgins.

It was a joy to observe this range of generations joining forces.

The March4Justice adds to the long history of feminists using public space in spectacular ways to draw attention to society’s gender problems. Anger, sorrow and issues surrounding sex run through this history.

But so too do themes of joy, hope and resilience.

The spectacle of women’s suffrage

Feminist protest in Australia began in the late 19th century, when women were galvanised en masse for the first time by the issue of voting rights. Many were angered by the inequality and violence they witnessed and faced on a daily basis. They saw the vote as the key to transforming society, believing it would allow them to elect leaders sympathetic to women’s rights.

As the historian Marilyn Lake explains in Getting Equal: The History of Australian Feminism, while all women lacked rights in the Australian colonies it was the plight of the married (white) woman that really captured suffragists’ attention. Upon marriage, women lost what little independence they had. They could not own property, easily file for divorce or maintain custody of their children.

The gender-based violence dominating feminist conversations in 2021 was also rife and politicised many early feminists. They were outraged wives had no personal autonomy and frequently suffered marital rape, unwanted childbearing, physical violence and economic control.

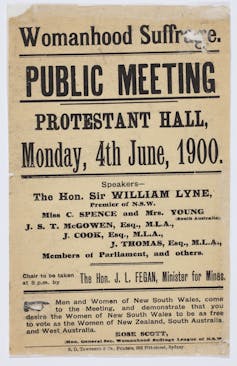

In response to this dismal situation, from the 1880s campaigns for women’s suffrage mounted. Local suffrage and other women’s organisations were formed and acted as pressure groups lobbying for change.

Read more: The long history of gender violence in Australia, and why it matters today

Activists like Louisa Lawson and Rose Scott made impassioned speeches, held public rallies and wrote to major newspapers to press for the vote, refusing to stay silent and submissive as was expected of women at this time.

Campaigns in Australia were more peaceful than elsewhere, but, like those marching for justice last week, suffragists were very much motivated by anger and frustration. They wanted to make a splash and used spectacle to bring attention to their efforts.

In 1891, Victorian women collected a massive 30,000 signatures on a 260-metre-long “monster petition”.

In 1898, two to three hundred women in the colony reportedly “invaded the club-room of the Legislative Council” to pressure members to pass a women’s suffrage bill.

Although unsuccessful at the time, the scale of these efforts revealed the force of women’s desire for change.

It is important to note the suffragists were almost exclusively concerned with the rights of white women like themselves. Aboriginal women — who endured even greater and more institutionalised forms of discrimination and violence — were not included in their vision for a new society based on equal rights. Then just as now, feminism had a significant race problem.

In 1902, white Australian women became the first in the world to enjoy the dual rights of voting and standing for parliament. They revelled in their new-found status as enfranchised citizens. But as daughters of the empire, they felt strongly connected to their British “sisters” and despaired they remained voteless after decades of protest. Some even travelled to Britain and contributed to its increasingly spectacular suffrage struggle.

Read more: Australian politics explainer: how women gained the right to vote

One Australian who captured imaginations in Britain was the performer and activist, Muriel Matters.

She was incensed by British women’s second-class status and, in 1908, famously chained herself to the iron grille separating the ladies’ gallery from the rest of the House of Commons, proclaiming “We have been behind this insulting grille too long!”

Both she and the grille — which many women saw as a symbol of their oppression — were removed in a dramatic scene, and Matters was sent to Holloway Prison.

The following year, Matters took her protest to the skies. Laden with a megaphone and 25 kilograms of flyers, and with a huge grin on her face, she crossed London in an airship emblazoned with the words “Votes for Women”.

There was a joyousness in this act of defiance. As Matters said: “If we want to go up in the air, neither the police nor anyone else can keep us down”.

Vida Goldstein was another Australian who made waves in London. In 1911, she was invited by Emmeline Pankhurst — whose suffrage organisation, the Women’s Social and Political Union, was infamous for its militant tactics — to travel to London, where she participated in the Women’s Suffrage Coronation Procession.

The scale of this event was huge. Over 40,000 people marched four miles across the city, in what Goldstein described as “the most amazing triumph of beauty and organisation”. They were watched by great crowds of spectators and ended with a rally at the Royal Albert Hall.

Goldstein, along with Margaret Fisher (the Australian prime minister’s wife) and Emily McGowen (the NSW premier’s wife), led the Australian contingent. This group carried a banner designed by Australian artist Dora Meeson Coates. It was adorned with the figures of two women — representing Britain and Australia — and the words “Trust the women mother as I have done”.

Vivid imagery and clever slogans continue to be part of feminist protests today.

The suffrage protests of the late 19th and early 20th centuries used spectacle to draw attention to women’s grievances. They were driven not only by anger and frustration, but also an enduring sense of hope that sustained them in the face of adversity.

The roar of Women’s Liberation

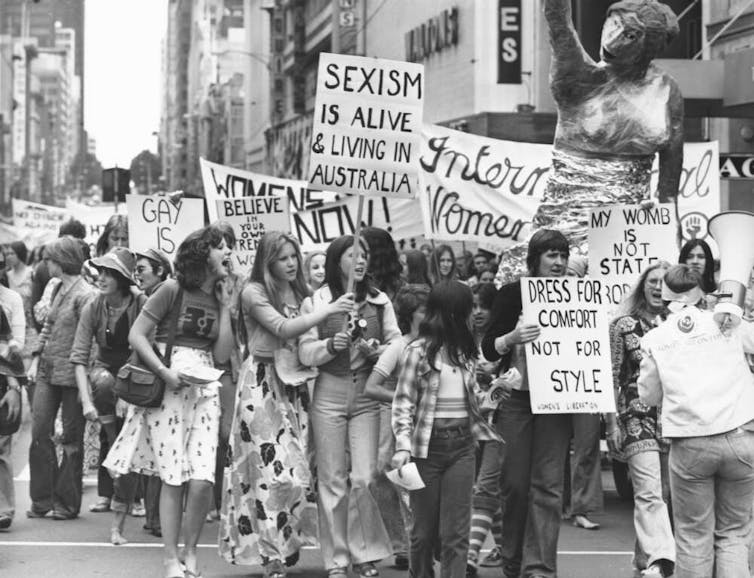

The many protest marches of the Women’s Liberation era of the 1960s and 1970s were also driven in good part by anger. They were spurred, among others, by issues of sex: legalising abortion; access to the pill; the sexual double standard; objectification of women’s bodies; sexual harassment; and violence against women.

The anger was palpable in the size and noise of the marches, the protesters’ willingness to disrupt city streets and public spaces, the eagerness to shock spectators through casual styles of dress, and the deployment of both occasional profanities and popular music.

Just as rage and roar have been used to describe the events surrounding the March4Justice, the Women’s Liberation anthem written and sung by Australian Helen Reddy featured the lines: “I am Woman, hear me roar, in numbers too big to ignore”.

Yet there was also a joy to some demonstrations of this protest era, especially the Women’s Liberation marches that allowed feminists to ventilate their rage, to prove to the world and themselves they were strong in number, sisterhood really was powerful and there were plenty of women who weren’t going to take it anymore.

Read more: Helen Reddy’s music made women feel invincible

Both the anger and the joy are well documented in the recent film Brazen Hussies. Brazen Hussies tells the story of the Australian Women’s Liberation movement from 1965 to 1975, covering its roots and rise.

Catherine Dwyer’s film provides insight into the anger fuelling the movement, from women’s individual stories of pain and injustice — the awful grief and trauma of having your baby taken from you because you weren’t married, the fury of being paid less for comparable work just because you were a woman, the trials of being a single mother, the enraging burden of shame due to the sexual double standard. And it covers the movement’s exclusion of Indigenous women and, to some extent, of lesbians through interviews with people like Pat O’Shane and Lilla Watson.

But there are also the triumphs and achievements: the legislative victories, the intellectual joys of feminist insights, the growing visibility of the movement.

That Australian Women’s Liberation was also marked by a sense of fun is perhaps best shown by a key event sparking the movement. On March 31, 1965, three Brisbane women dramatically protested their exclusion from the front bar at the Regatta Hotel in Toowong. When they were refused service (as was customary at the time for women in a front bar), two of the women chained themselves to the bar footrail, and the third took the key and threw it into the river.

It took hours for the police to remove the chain, and the event won an enormous amount of publicity.

Merle Thornton, Rosalie Bognor and Elaine Dignan were consciously playing on history when they staged this event, evoking the proclivity of suffragettes to chain themselves to fixed objects. It was also a clear echo of the moment when Muriel Matters chained herself to the grille in the House of Commons over 50 years before.

The fact protesters at the March4Justice were urged to wear black, and many did, signals a vital difference in its overall emotional affect compared to such earlier moments of fun.

The sombre colour of the rallies on March 15 was in stark contrast to the international suffragettes’ customary white dresses (with green and purple sashes), or the Women’s Liberation style of blue denim and colourful t-shirts, hippy skirts and dresses.

Black is the colour of sorrow, which was evident last Monday alongside the anger: sorrow at the terrible pain and suffering of women who are harassed, assaulted and raped, and not able to speak up, or are denied justice.

And sorrow at the fact women are still being harassed, assaulted and raped.

But even stronger than the sorrow was the anger at the Morrison government’s failure to deal with the assaults and allegations, or even to send a representative to the protest happening at its front door.

Fighting gender-based violence in 2021

Looking back at the history of feminist protest highlights striking continuities in the nature of gender-based violence and discrimination over time.

It shows the various ways women’s bodies have been controlled and abused.

It reveals how feminists have persistently protested their subordination, taking up space and refusing to be silenced. Anger, frustration and despair have driven people to action. Optimism, resilience and joy have empowered women to keep fighting even in the face of significant barriers.

21st century feminists are building on a substantial legacy of women’s protest. They are also grappling with the limits of feminisms past and present.

Indigenous women, leaders and community groups participated in many of the rallies around the country last week, drawing attention to the extensive trauma First Nations women have endured and continue to face. Their presence called for feminists to meaningfully engage with issues of race and to help end systemic injustice in the era of Black Lives Matter.

Trans and non-binary activists are calling for recognition gender-based violence disproportionately affects gender-diverse people. Feminists of the past largely viewed their fight through a gender binary. The challenge for today’s activists is to move beyond this.

Intersectionality exists as an ideal; the challenge now is to meaningfully put it into practice.

It remains to be seen what will come of the March4Justice and whether it lasts as a genuinely transformative cultural moment. What is sure, despite the many hurdles they have faced, Australian feminists have consistently found creative and captivating ways to express their indignation and visions for a better future. Feminists today can find inspiration in — and learn from — the various moments and the people who have shaped this history.

Brazen Hussies is now available on ABC iView, and will be broadcast nationally on ABC TV on Monday 5 April at 8.30 pm.

– ref. Friday essay: Sex, power and anger — a history of feminist protests in Australia – https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-sex-power-and-anger-a-history-of-feminist-protests-in-australia-157402