Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Victoria Grieve Williams, Adjunct Professor, RMIT University

There is a quiet movement among settler colonials in Australia and the US to critically examine their family histories as a way of re-examining the impact of centuries of dispossession and slavery of Indigenous peoples.

Critical family histories enable a shift from celebratory tropes of benign settlement to deep considerations of legitimacy. The myth of great white men and women, bravely opening new worlds and taming the wilderness, including the “savage” Indigenes, is now being challenged by a search for the truth.

As Diane Kenaston, an American pastor and genealogist, explains in her book Genealogy and Anti-Racism: A Resource for White People, genealogy has long been entwined with white supremacy. And family history research has been the preserve of white privilege.

But, she writes, critical family history can also “change the narratives within our own families”.

Our ancestors were works in progress, just as we are. They, like us, sometimes participated in oppressive systems and sometimes resisted them. [We need to] engage this complex legacy.

Read more: Friday essay: the ‘great Australian silence’ 50 years on

Education activist Christine Sleeter first adopted the use of critical family history in this way. While researching teaching methods for the multicultural classroom, she discovered that intersections of race, class, culture, gender and other forms of difference and power had shaped her own family history.

In her research, Sleeter found

a history and legacy of not only European American immigration, but also of Appalachia, of slave ownership, of African Americans passing as white and leaving family behind, and of Jim Crow.

Her awareness led to a sense of responsibility and debt. In 2017, she returned to the Ute people US$250,000, which she had inherited from the sale of a homestead on land stolen from the Ute people in Colorado in 1881.

Founding fathers as ancestors

In Australia, David Denborough, a writer and academic, thought there would be nothing of interest in the stories of his ancestors.

Working alongside Aboriginal people, documenting their stories of dispossession and survival, he was challenged by Jane Lester, a Yangkunytjatjara/Antikirinya woman, to find his ancestors.

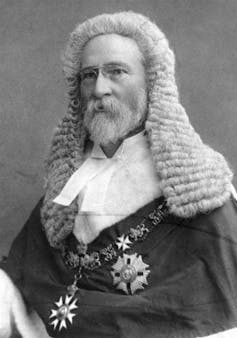

Now, 20 years later, he is publishing a book of letters to his great-great-grandfather, Sir Samuel Walker Griffith.

Griffith, a celebrated founding father of Australia, was premier of Queensland during the “killing times” and later became the country’s first chief justice.

The relationships between Denborough’s ancestors and Aboriginal people were marked by colonisation, racism and often inhumane treatment. While Griffith wrote terra nullius into the Australian constitution, another ancestor, Charles Cummins Stone Anning, was responsible for atrocities against Aboriginal people in Queensland.

Denborough is determined to tell the truth as part of his healing journey and his close relationship with Aboriginal people. He has realised

there is no sense in moral superiority towards my ancestry because colonial violence in this country has not ended; no place for hopelessness because First Nations resistance has never wavered; and, no time for paralysing shame because invitations to partnerships are still being offered by Aboriginal people … and [there is] so much to be done.

White deaths at black hands, black deaths at white hands

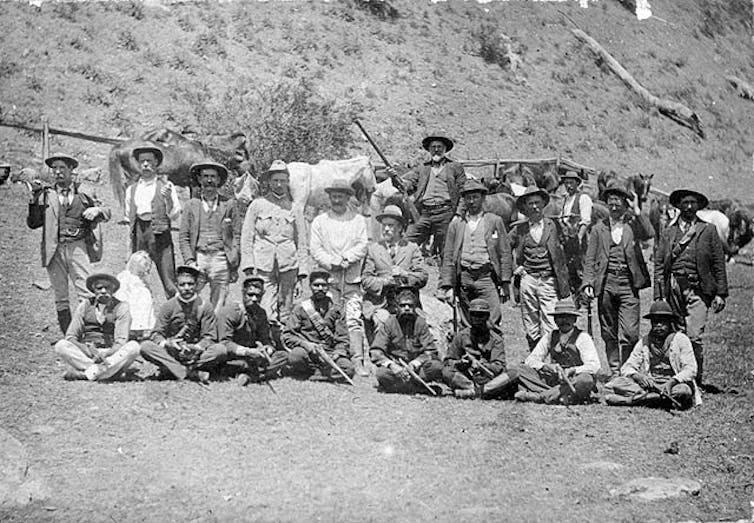

James Brown was 16 years old and shepherding alone on a remote sheep run near present-day Quorn, South Australia, in 1852. He was found tragically clubbed to death and mutilated in unknown circumstances.

An unwritten rule of the frontier was that attacks on white people, no matter the circumstances, were followed by vigilante violence. Men, women and children were often massacred in retribution.

Seventeen men, including Brown’s brothers and two Aboriginal trackers, rode out. They reported killing four Aboriginal men. Tellingly, though, two of the 15 men would not swear this on the Bible.

Mike Brown, a descendent of this family who took over land in the Flinders Ranges area, knew very little of the Aboriginal history of Australia. After hearing Reg Blow, a Gureng Gureng elder, speak about the true history of the criminal takeover of Aboriginal lands, Brown was inspired to research his own family history.

Read more: Friday essay: masters of the future or heirs of the past? Mining, history and Indigenous ownership

Wanting to investigate the Aboriginal stories of the 1852 massacre, he found a lifetime friend in Ken McKenzie, a prominent Andyamuthna elder, from whom he received “the dignity of forgiveness”.

Brown is now working with others on a documentary, Beyond Sorry, to reveal the full story of the massacre. He told me,

It’s how we discover who we really are as a people and our relationship to this land […] we need to be released from the illusion we live under that affects our attitudes to ‘others’, to be free.

In NSW, playwright Clare Britton was also shocked to discover the story of brutally murdered relatives in her family history.

The pregnant Elizabeth O’Brien and her infant son Poggy were clubbed to death by the Aboriginal “bushrangers” Jimmy and Joe Governor in 1900. With the help of descendents of the Governor family and Aboriginal elders, Britton’s theatre company produced a play based on this story, Posts in a Paddock. The title refers to all that remained of the O’Brien household when she visited, a stark memorial to the family tragedy.

Britton explained that elder Aunty Rhonda Dixon Grovenor introduced the concept of dadirri “deep listening” to the ensemble. They sat with their Aboriginal collaborators and each other’s families. And listened to each other. She said,

so many Indigenous people were killed, separated from their families and taken away from their homes and you can’t read about that in the same way because those stories were not recorded. [These murders] were thoroughly documented because my family and the other victims were white.

The understandings I formed then have changed me.

Giving back

In the US, artist Anne Mavor was inspired to learn about her ancestors after attending a public meeting where a local Indigenous person challenged the white audience to critically examine their histories.

Mavor put together an exhibition, I Am My White Ancestors: Claiming the Legacy of Oppression, comprised of 12 pieces of art depicting her ancestors. They include royal figures, a slave owner, warriors, farmers and a pilgrim — all with Mavor’s face. The life-size portraits make whiteness visible and accountable.

Mavor told me she seeks

to inspire white viewers … to claim both positive and negative aspects of their own family histories to contribute to the end of racism.

She says white people don’t get a pass by ignoring the oppression of their ancestors. They need to ask: What is the legacy of this oppression and how does this affect me now?

This is just one of many projects designed to give back to Indigenous peoples. In Seattle, residents can pay rent to the city’s first inhabitants, the Duwamish people, who have long been rejected by the US government for federal recognition as a Native American tribe.

Read more: Explorer, navigator, coloniser: revisit Captain Cook’s legacy with the click of a mouse

The Coalition of Anti-Racist Whites has developed the “Real Rent” program as a means of restitution, but also to educate the broader public about the plight of the Duwamish.

Another project, Reconciliation Rising, coordinated by Lakota journalist Kevin Abourezk and academic Margaret Jacobs, showcases the work of those engaged in confronting painful and traumatic histories as a way towards reconciliation.

Their website lists examples of apologies, notable activists and many instances of the return of ancestral lands.

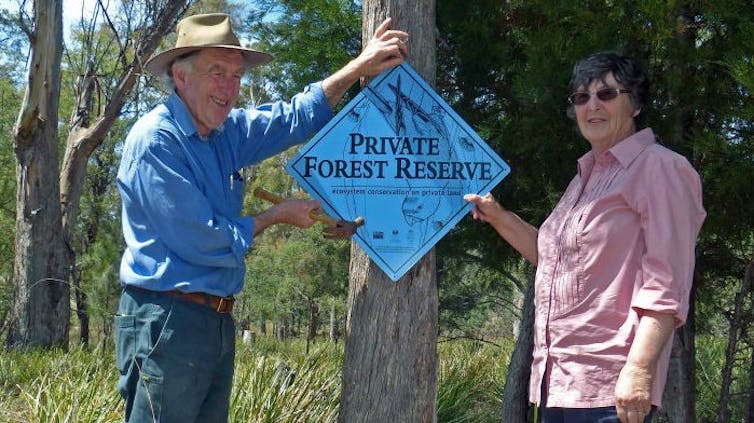

Land hand-backs are happening in Australia, too. Tom and Jane Teniswood have returned half of their 220-acre property in Tasmania to the local Aboriginal community. The Teniswoods advocate individual action over government reconciliation efforts, saying

reconciliation is great but it is so much talk, so many documents and so little action. This is just a symbol of action.

It is easy to agree with them. While government leadership in truth-telling is vital, we will see more of these acts of profound generosity and genuine reconciliation from settler colonials.

In the spirit of Makaratta

Settler colonials are beginning to understand the true impacts of the criminal takeover of Indigenous lands. They are seeking to right the balance and achieve a spiritual resolution.

This is the Aboriginal way of approaching history, in order to move forward after a conflict. A common process across the continent, it is called Makaratta by the yolngu people of Arnhemland. In the same way, a critical approach to family histories involves a great deal of communication between settler colonials and Indigenous peoples. It enables the forging of new relationships.

It is histories such as these that will change people through deep understanding and empathy. They also present an opportunity to truly and indelibly change the nature of our society and leave a meaningful legacy for our children.

– ref. Truth telling and giving back: how settler colonials are coming to terms with painful family histories – https://theconversation.com/truth-telling-and-giving-back-how-settler-colonials-are-coming-to-terms-with-painful-family-histories-145165