Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Scott Davie, Lecturer in Piano, School of Music, Australian National University

It seems safe to assume a musical “masterpiece” would show compositional magnificence and garner universal acclaim — yet Maurice Ravel’s Boléro (1928) is conspicuously lacking in the first.

Writing to a friend shortly after finishing the work, Ravel described it as having “no form in the true sense of the word, no development, and hardly any modulation”. And to the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger, he confided, “I’ve written only one masterpiece – Boléro. Unfortunately, there’s no music in it”.

Despite these misgivings, Boléro’s instant success was a delightful surprise for the composer. A few years later, on entering the casino at Monte Carlo, he was asked if he would like to gamble. He declined by saying, “I wrote Boléro and won — I’ll let it go at that”.

Read more: New music composers face the age-old question: do they write for themselves or for mass appeal?

Ballet beginnings

The piece arose out of a commission for a new ballet from Ida Rubinstein, a prominent dancer formerly with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Originally, Ravel had planned to respond with an orchestration of Spanish composer Isaac Albeniz’s Iberia (1905–1908), but when copyright issues proved insurmountable, he decided to write his own Spanish-themed work.The Spanish influence is not surprising in a work by France’s then-most-famous composer, as his mother was Basques. Nor are the obvious inflections of jazz, as the style was popular in many of the bars of Paris frequented by Ravel, and his four-month tour of the United States early in 1928 had heightened the attraction.

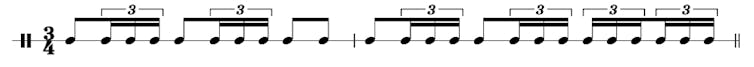

What is truly surprising is the singular premise on which Boléro is based: an experimental orchestral crescendo lasting a quarter of an hour, based exclusively on a two-bar rhythm repeated a staggering 169 times.

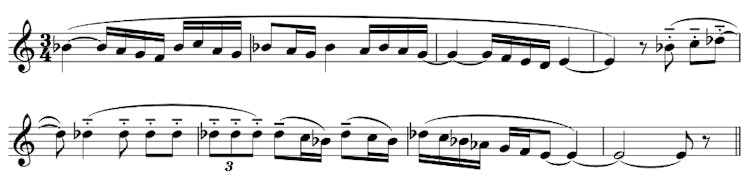

There are but two melodic ideas in the piece, each heard twice before alternating, and always given to a new instrument or group of instruments.

Indeed, for a composer famous for his orchestration — both in his own compositions and in his arrangement of works by others — it is a marvel of orchestral assignment, writing for each instrument (and instrumental group) in ways that highlight particular aspects unique to them.

It is amusing to imagine Ravel, a self-confessed “dandy”, who once played the melody on piano for a friend, dressed in a yellow dressing down and scarlet head cap. “Don’t you think this theme has an insistent quality?” he reportedly asked.

The second melody contrasts with evocative repeated notes that have a flattened quality to them, these blue-note intonations no doubt contributing to what Ravel’s friend, Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, believed were “obsessive, musico-sexual” underpinnings in the work.

The gamble pays off

Almost immediately, the work found success in the concert hall, with recordings by luminary conductors like Sergei Koussevitzky and Willem Mengelberg. The popularity of the work in the United States was aided through performances led by Arturo Toscanini. Ravel, however, did not hide his scorn for the conductor’s interpretation: at around 13 minutes long, Ravel believed that it was played too fast. The composer’s own recording lasts over 16 minutes.

Toscanini believed that the work needed “saving”, yet it is arguable that, at the slower speed requested by the composer, audiences are beguiled into a state of complete enthralment. The more moderate tempo also fits better with our understanding of the composer, who had a lifelong fascination with mechanical devices.

Read more: Performing Beethoven – what it feels like to embody a master on today’s stage

Indeed, Ravel’s original scenario for the ballet built on this mechanistic idea, with the action to have taken place within a factory. In Alexandre Benois’s designs for the first production, however, the ballet was set in a Spanish tavern.

The combination of sinuous melody, mesmeric rhythm, and slowly building orchestral crescendo has inspired the imagination of Hollywood. In 1934, a film starring George Raft and Carole Lombard titled Bolero made much of the simmering tension underpinning the work.

In 1979, the music was similarly used to illustrate Dudley Moore’s attraction to Bo Derek in 10.

And to universal acclaim, gold medal-winning ice-skating duo, Torvill and Dean, danced to a (considerably shortened) recording of the piece at the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics.

Detractors

Yet there is no escaping that the singular premise of Boléro fuels the claim it is a composition with little content. According to the composer’s brother Edouard, this criticism was evident at a first performance, where an old lady was heard shouting “Rubbish! Rubbish!” above the applause. On being informed of this, the composer responded sagely, saying, “That old lady got the message”.

Sarcastic remarks on Ravel’s works were made by the British composer, Constant Lambert. He claimed that in some of the composer’s pieces the repeated rhythms eventually grew tiresome. This was even more of a problem with Boléro, he stated, as it occurs “shortly after the beginning”.

Perhaps the funniest response to the work is Patrice Leconte’s short film, Le batteur do Boléro, first shown at the Cannes Film Festival in 1992. After the conductor walks to the stage and the orchestra begins, the camera pans to the back of the stage, the focus landing on the percussionist tasked with playing the incessantly repetitive rhythm. The facial movements of the drummer as he endures this undertaking amount to a farcical study of the difficulties of maintaining attention, and is endlessly amusing.

The ending

Sadly, the work was one of the composer’s last, an accident in a Paris taxi exacerbating what was possibly a latent neurological condition which drew his life to an end within a decade, incapacitated mentally and in pain.

While the work has proven easy to criticise, there is an element that nevertheless marks Boléro as deserving of lasting attention. Given the repetitive rhythm and the restricted melodic material, it would have been foremost in Ravel’s mind that monotony would be an issue, even with his carefully expanding orchestration. Especially in terms of its harmony, the piece is utterly welded to the key of C major.

Yet with a master’s understanding of the intricacies of timing, Ravel rachets the ending in two ways.

Firstly, he curtails the double statements of the two themes to single playings. And then, without warning, he moves the entire piece to the key of E major, a harmonically “distant” key with little relation to the home key of C major. And then, after eight glorious bars of peeling forth in this previously unimaginable harmonic region, he just as suddenly moves the music back again.

Given the unceasing momentum of all that has gone before, the momentary harmonic shift serves to satisfy our need for change, seemingly in an instant. And with this simple roll of the dice, Ravel likely guaranteed the lasting success of this masterpiece “without any music in it”.

Read more: Decoding the music masterpieces: Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances

– ref. Decoding the music masterpieces: Ravel’s Bolero — a sinuous and sexy composition with ‘no music in it’ – https://theconversation.com/decoding-the-music-masterpieces-ravels-bolero-a-sinuous-and-sexy-composition-with-no-music-in-it-149528