Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Amy Boyle, PhD Candidate, University of Wollongong

In a new series, writers pay tribute to fictional detectives on the page and screen.

When Jessica Jones slunk onto screens in 2015, it was only fitting for the series in which she featured to begin in the shadows of Hell’s Kitchen. As the first superpowered female lead in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (albeit, on Netflix rather than in movie theatres), Jones existed on the margins.

Like others, I had been waiting for a female-led Marvel film while becoming disenfranchised by its offerings. By the time Jessica Jones came around, I was completely ambivalent and somewhat despondent. It was a welcome surprise that Jones (played by Krysten Ritter) was different — and not just because she was a woman.

Part superhero, but mainly hardboiled private eye, Jones was a departure from the superhero we had gotten used to, and the detectives too.

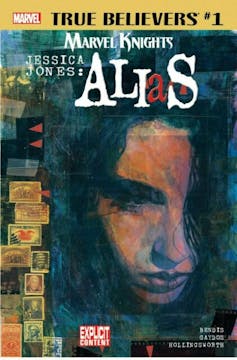

Adapted from Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Gaydos’s Alias comic book series, Jessica Jones merges the superhero and crime drama genres to ask provocative questions about power, justice and authority.Jessica who?

Jones is plagued by questions of what justice means and what it means to be a hero.

She has no time for martial arts or neat explanations. She is reluctant to take on the identity of a crime-fighting hero at all because she’s extremely sceptical that there is such a thing.

Whenever the word “hero” leaves her mouth, it’s with a degree of distaste. Her detachment is refreshing after no less than three Iron Man films and countless heroic crime drama series. By the time we meet Jones, as critic Kathryn VanArendonk puts it:

the detective has become her own breed of superhero – a figure who restores the status quo […] She brings order out of chaos. She finds answers. She is superhuman.“

On the surface, Jones might seem a reluctant female hero, like Buffy in the early seasons of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003). But sitting alongside the wider Marvel universe, though Jones helps others between paying clients, her scepticism makes things complicated.

Read more: Friday essay: Hail Hydra – on comics, ethics and politics

Ambivalent origins

Far from making her invincible to external threats, Jones’ superpowers leave her vulnerable to fetishisation and gender-based violence at the hands of series villain Kilgrave. Played by David Tennant, Kilgrave has been interpreted as a metaphor for white, hetero-patriarchal control and toxic masculinity.

In contrast to other superheroes, Jones’ traumas lead her not to reassert herself as a crime-fighting hero but to reassess the validity of the whole hero narrative. She trades the promise of a costume (which she notably never dons in the television series) for a camera, and becomes a morally ambivalent private investigator.

Law and order

At the intersection of superhero and crime drama, Jessica Jones raises important questions about the law and social justice.

Superhero and crime drama genres are generally conservative in terms of tone, politics and gender roles. While there are self-critical deviations, their premises often rely on a sequence: the establishment of status quo, it’s disruption by crime and villainy, and the triumphant reestablishment at the hands of a superhero or crime-fighting detective.

In the face of violence and injustice, the solution is often meted out by a kind of vigilante who, hero or antihero, becomes synonymous with the law.

As a jaded super-detective, Jones questions not only the status quo but the notion of the vigilante hero and their perceived synonym with social justice. She never gives up a chance to call out others’ “heroism” for hubris or self-indulgence.

Read more: Remember Blockbuster, Nirvana and pagers? The new Captain Marvel lives in the 1990s

Evoking crime noir, Jones eschews the black and white to reside in the greys, purples and in-betweens. She’s unconvinced as to whether anyone can or should have the moral authority to decide what is right or wrong.

This detachment rarely wavers. Over the course of three seasons and a team-up in The Defenders (2017), Jones’ dry scepticism is hilariously charged at everyone including herself and her Netflix Marvel counterparts.

Read more: My favourite detective: Sam Spade, as hard as nails and the smartest guy in the room

Critics haven’t always been sure how to respond. Jones’ ambiguity as female antihero resulted in the character and series being simultaneously praised and denounced. Critic Stassa Edwards celebrated it as “slow unravelling of a familiar genre”, while Eric Kain argued Jones had no place in the Marvel cinematic universe.

Indeed, through her wry characterisation as jaded super-detective, Jones provides irreverent commentary on the masculine grandiosity and oft-undisputed entitlement of the superhero, and its pervasion into neighbouring genres. If internet sleuths read this disparity as a clue to Jessica Jones’s not-belonging, they might have just solved the case.

– ref. My favourite detective: Jessica Jones, a super-detective for the Marvel generation – https://theconversation.com/my-favourite-detective-jessica-jones-a-super-detective-for-the-marvel-generation-149542