Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Daryl Sparkes, Senior Lecturer (Media Studies and Production), University of Southern Queensland

In a new series, writers pay tribute to fictional detectives on page and on screen.

Hard-boiled doesn’t come close to describing Sam Spade.

He’s the original Private Investigator on which all other PIs are based. You’ll be very glad to have him on your side, and terrified to have him as your opponent.

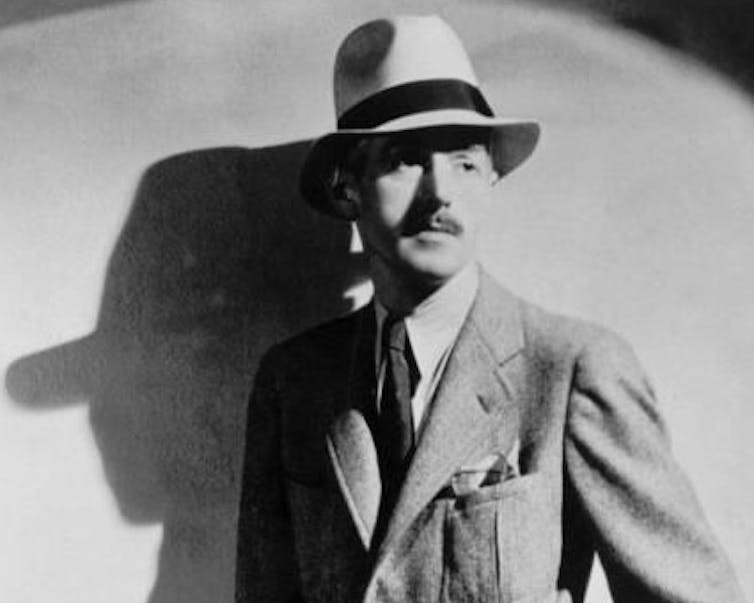

Spade was the invention of the great noir crime writer, Dashiell Hammett, who published his first novel in 1929. Spade is often overlooked for the dashing Philip Marlowe, created by the more well-known crime writer, Raymond Chandler, who began publishing soon after Hammett stopped in the late 1930s.

Chandler was clearly influenced by Hammett, with Marlowe and Spade sharing many of the same qualities — tough, no-nonsense, hard-drinking and wise-cracking. Both are morally upright. And they share an eye for the ladies. But I’ve always thought that Spade was smarter than Marlowe, and had a deeper insight into the human condition, especially when that condition involved murder, blackmail and theft.

Serial contender

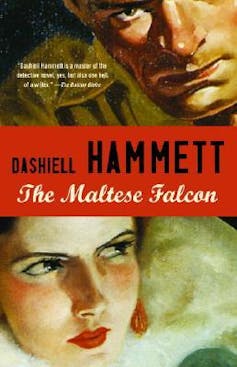

Spade and the first story he appeared in, The Maltese Falcon, made their debut in the 1920s Black Mask magazine, serialised over five editions.

Hammett wrote four other Spade stories for different magazines, collected in A Man called Spade and Other Stories. He also created the characters of Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man) and the Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse).

In The Maltese Falcon, Spade investigates the sudden murder of his partner, Miles Archer, while fending off a myriad of shady characters — Joel Cairo, Wilmer Cook, Kasper Gutman and Spade’s love interest, Brigid O’Shaughnessy — all focused on locating a stolen fabled gold and jewelled black falcon figure. It was so popular it was soon released as a novel.

Humphrey Bogart played Spade in the second film portrayal, which became a hit when it was screeened in 1941. He portrayed Spade as Hammett described him:

Spade has no original … For your private detective does not … want to be an erudite solver of riddles in the Sherlock Holmes manner; he wants to be a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody he comes in contact with, whether criminal, innocent bystander or client.

Read more: My favourite detective: Kurt Wallander — too grumpy to like, relatable enough to get under your skin

A hardened cynic

Spade isn’t just some rough and ready thug. He’s got smarts about him. Not just street smarts, but a psychological insight into what drives people to do the things they do. And he knows that motivation is often driven by greed, investigating according to the edict of “Follow the Money” some 47 years before the saying was uttered in the All the President’s Men.

Spade looks at others through a prism of distrust, dishonesty and deceit. But with his own personal honour intact. The fantastic thing about Spade, which you don’t realise until the end of The Maltese Falcon, is that he knows every single person he comes across is a liar and a fraud.

In his cynical and sceptical manner, he never believes anything anyone says to him at any stage.

Spade’s whole masterful performance is in pretending to believe each liar, to lull them into thinking he’s an easily manipulated stooge, while giving each of the other characters enough rope to, in some cases literally, hang themselves.

The magic of The Maltese Falcon is watching the liars try to out lie each other while Spade stands there chuckling to himself and pretending to believe their tangling webs of fiction.

Even when he makes out that he’s desperate, that his life is on the line as the police try to pin his partner’s murder on him, it is only a ploy to get the liars to stretch their version of the truth even thinner, and thus reveal their intentions even more clearly.

That’s where Spade’s charisma comes from. He’s the lone honest man in a room, playing all the players.

Read more: My favourite detective: Trixie Belden, the uncool girl sleuth with a sensitive moral compass

And loving it …

Put another way, he’s also a bit of a sadist. He enjoys seeing the liars turn and twist in the wind, always having the last laugh.

Spade knows there’s no honour amongst thieves so he plays Cairo, Gutman, Cook, and O’Shaughnessy off against each other, seeing who can be the most debased in their greed for the Falcon.

Coincidentally, Bogart played Philip Marlowe in Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1946) five years after The Maltese Falcon. And while Bogart lends both characters his distinctive delivery, there are major differences. Marlowe is not as edgy as Spade. He’s more trusting — a sucker for a pretty face. Spade isn’t any of these.

At the end of The Maltese Falcon, Brigid O’Shaughnessy accuses Spade of just pretending to love her because he is going to hand her over to the police for murder. But he responds, “I don’t care who loves who! I won’t play the sap!”

And even though Spade truly does love her, and will agonise over the decision to do so for the rest of his life, he still turns her in. That’s because Spade doesn’t play the sap for anyone.

He’s smarter and he’s made of stronger stuff than the rest of us. Maybe even something worth more than what he tells the cops is inside the black bird: “The stuff dreams are made of”.

Read more: Beauty and brawn: Lauren Bacall’s noir feminine legacy

– ref. My favourite detective: Sam Spade, as hard as nails and the smartest guy in the room – https://theconversation.com/my-favourite-detective-sam-spade-as-hard-as-nails-and-the-smartest-guy-in-the-room-149295