Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Dimitri Perrin, Senior Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology

Genetic engineering has already cemented itself as an invaluable tool for studying gene functions in organisms.

Our new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, now demonstrates how gene editing can be used to pinpoint genes involved in corals’ ability to withstand heat stress.

A better understanding of such genes will lay the groundwork for experts to predict the natural response of coral populations to climate change. And this could guide efforts to improve coral adaptation, through the selective breeding of naturally heat-tolerant corals.

A threatened national treasure

The Great Barrier Reef is among the world’s most awe-inspiring, unique and economically valuable ecosystems. It spans more than 2,000 kilometres, has more than 600 types of coral, 1,600 types of fish and is of immense cultural significance — especially for Traditional Owners.

But warming ocean waters caused by climate change are leading to the mass bleaching and mortality of corals on the reef, threatening the reef’s long-term survival.Read more: The first step to conserving the Great Barrier Reef is understanding what lives there

Many research efforts are focused on how we can prevent the reef’s deterioration by helping it adapt to and recover from the conditions causing it stress.

Understanding the genes and molecular pathways that protect corals from heat stress will be key to achieving these goals.

While hypotheses exist about the roles of particular genes and pathways, rigorous testings of these have been difficult — largely due to a lack of tools to determine gene function in corals.

But over the past decade or so, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has emerged as a powerful tool to study gene function in non-model organisms.

CRISPR: a technological marvel

Scientists can use CRISPR to make precise changes to the DNA of a living organisms, by “cutting” its DNA and editing the sequence. This can involve inactivating a specific gene, introducing a new piece of DNA or replacing a piece.

In our 2018 research, we showed it is possible to make precise mutations in the coral genome using CRISPR technology. However, we were unable to determine the functions of our specific target genes.

For our latest research, we used an updated CRISPR method to sufficiently disrupt the Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1, or HSF1, in coral larvae.

Based on this protein-coding gene’s role in model organisms, including closely related sea anemones, we hypothesised it would play an important role in the heat response of corals.

Past research had also demonstrated HSF1 can influence a large number of heat response genes, acting as a kind of “master switch” to turn them on.

By inactivating this master switch, we expected to see significant changes in the corals’ heat tolerance. Our prediction proved accurate.

Read more: What is CRISPR, the gene editing technology that won the Chemistry Nobel prize?

What we discovered by injecting coral eggs

We spawned corals at the Australian Institute of Marine Science during the annual mass spawning event in November, 2018.

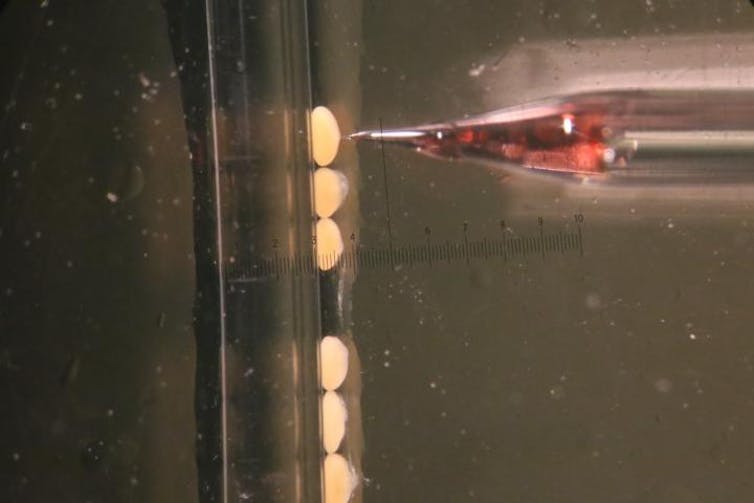

We then injected CRISPR/Cas9 components into fertilised coral eggs to target the HSF1 gene in the common and widespread staghorn coral Acropora millepora.

We were able to demonstrate a strong effect of HSF1 on corals’ heat tolerance. Specifically, when this gene was mutated using CRISPR (and no longer functional) the corals were more vulnerable to heat stress.

Larvae with knocked-out copies of HSF1 died under heat stress when the water temperature was increased from 27℃ to 34℃. In contrast, larvae with the functional gene survived well in the warmer water.

Let’s understand what we already have

It may be tempting now to focus on using gene-editing tools to engineer heat-resistant strains of corals, to fast-track the Great Barrier Reef’s adaptation to warming waters.

However, genetic engineering should first and foremost be used to increase our knowledge of the fundamental biology of corals and other reef organisms, including their response to heat stress.

Not only will this help us more accurately predict the natural response of coral reefs to a changing climate, it will also shed light on the risks and benefits of new management tools for corals, such as selective breeding.

It is our hope these genetic insights will provide a solid foundation for future reef conservation and management efforts.

– ref. Gene editing is revealing how corals respond to warming waters. It could transform how we manage our reefs – https://theconversation.com/gene-editing-is-revealing-how-corals-respond-to-warming-waters-it-could-transform-how-we-manage-our-reefs-143444