Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alana Piper, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Technology Sydney

The Black Lives Matters movement in the United States and Australia has drawn welcome attention to Black deaths in the criminal justice system. Such fatalities are extreme manifestations of a long history of excessive punishment of Black bodies: from the use of neck chains on Indigenous Australian prisoners into the 1940s to their over-incarceration for minor offences today.

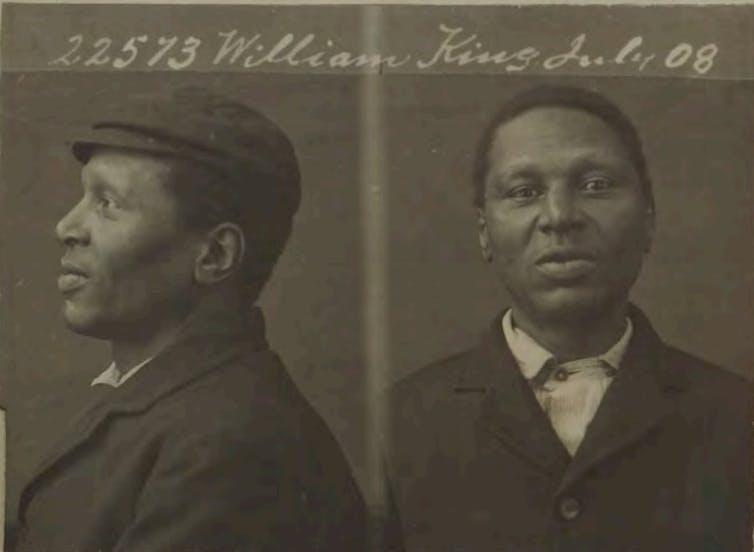

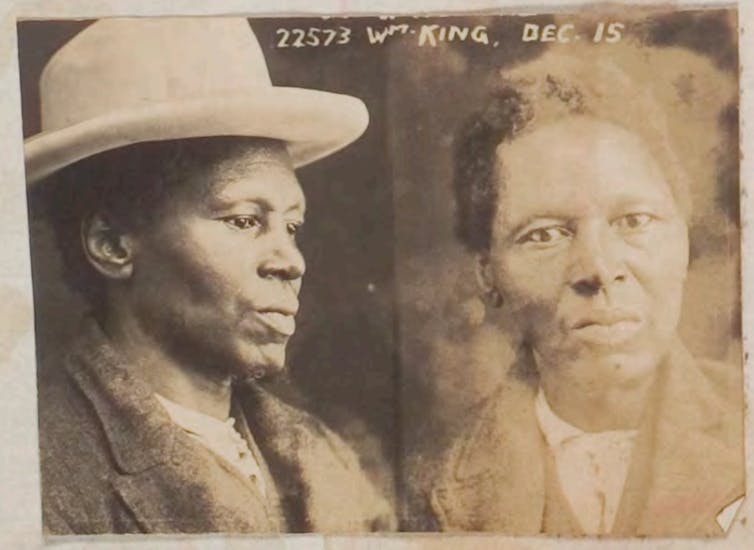

One historical case that demonstrates this in Australia is that of William King, an African-American sailor who arrived in Melbourne in 1887. Little is known about King’s life before this but the following year he was convicted for burglary and sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour. Thus began a cycle in and out of prison.

King’s second conviction in 1889 — on four charges of receiving stolen goods — earned him nine years’ imprisonment. This sentence was unusually steep. Data on prosecutions for this crime in Victoria during the 1880s show the vast bulk of offenders were sentenced to less than two years in prison, even when facing multiple charges.

Even more remarkable is the wide range of additional punishments King was subjected to in prison.‘Insolence’

Prison records show during his time in Pentridge, King was punished for 53 infractions of prison discipline, far more than any other prisoner at the time. These infractions, mostly consisting of “insolence” or “disobedience of orders”, were punished by stints of solitary confinement, months spent wearing heavy, iron chains and an extension of his original sentence.

King was a problematic individual. But the colour of his skin probably engendered hostility from the guards or increased their perception he was a dangerous offender in need of rigid control. King later said he believed his race had made him a target.

Public attention was drawn to King’s treatment in 1898 when an anonymous informant — most likely a former inmate — alerted socialist newspaper The Tocsin to his plight.

In a lengthy exposé, the paper alleged prison guards not only deliberately targeted King by imposing groundless punishments on him, but even ganged up to give him beatings at night. King had spent more than 100 days in solitary confinement in the previous year alone.

Continued media attention may have prompted the decision to release King by “special authority” in 1900.

Just six weeks later he was convicted on two counts of burglary. At his trial, King said he would “rather be hanged” than return to prison. He alleged continual police persecution following his release, and said he was merely a convenient suspect for the crimes.

While King’s assertions of innocence must be read with a grain of salt, officials at the time were undoubtedly influenced by pervading racist rhetoric that associated Black men with increased criminality and violence.

Read more: Why the Black Lives Matter protests must continue: an urgent appeal by Marcia Langton

‘Big, burly, repulsive’

One of the detectives who worked the 1900 case, David George O’Donnell, tellingly recalled King in his later reminiscences as “a big, burly, repulsive looking American nigger … absolutely dangerous to life and limb”.

King’s return to prison was marked by further infractions and solitary confinement. In 1908, he was released for only a month before again being convicted of burglary. Declared a habitual criminal under the 1907 Indeterminate Sentences Act, King was remanded to prison indefinitely.

In 1909, King was convicted of stabbing prison guard William Sharp in the cheek with a knife. King claimed Sharp had brought the knife into his cell, and had been stabbed as King tried to get it away from him. As a result, King spent even more time in solitary confinement.

Later that year, Pentridge’s medical officer expressed concerns about the toll lengthy solitary stays were having on King’s mental and physical health after he lost ten pounds (4.5 kilograms) in just one week.

Read more: From molten lava to cobbled laneways: how bluestone shaped Melbourne’s identity

The use of solitary confinement against King was halted for several months — until he stabbed another warder. King’s defence was that he had been held down and beaten by five warders until he had managed to draw out a knife to defend himself.

King’s final trial occurred in 1911, this time for attempted murder of a guard. While admitting the offence, King again claimed to have been defending himself after repeated, racially-motivated violence from both guards and fellow prisoners.

‘Treated like a wild beast’

He claimed to have been treated “not like an ordinary prisoner, but more like a wild beast”. The jury appears to have been sympathetic, returning a verdict of not guilty.

King remained incarcerated until 1916, when the government ordered his release on the condition he be immediately deported to the US. Police escorted King on board the ship Puacko, bound for San Francisco.

According to Detective O’Donnell’s memoir, the vessel’s Captain told King if they had any trouble from him during the voyage, a quick burial at sea would mean there would be no coroner’s inquest.

King was indeed buried at sea during the voyage. His cause of death was recorded as a stomach complaint.

– ref. The tale of ‘habitual criminal’ William King: a Black life in Victoria’s white justice system – https://theconversation.com/the-tale-of-habitual-criminal-william-king-a-black-life-in-victorias-white-justice-system-147274