ANALYSIS: By Graham Davis

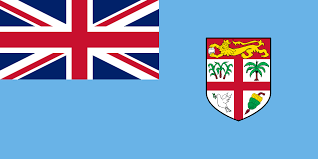

As the national flag – Fiji’s “noble banner blue” – flew over the celebrations at the weekend marking the 50th anniversary of Independence, it’s worth remembering just how close Voreqe Bainimarama and Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum came five years ago to getting rid of it altogether.

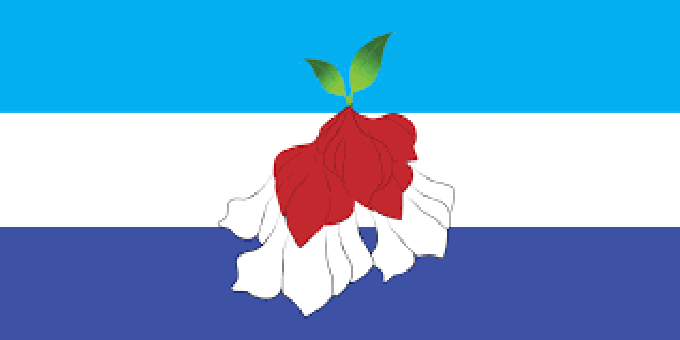

The display photo is of one of the 23 designs that emerged from a national competition in 2015 to choose a new flag and happens to have been the Attorney-General’s personal choice.

What is it? Well may you ask because it is far from immediately obvious.

It’s a Medinilla waterhousei – to give it its formal botanical name – commonly known in Fiji as the tagimoucia – the famous species of flowering plant in the family Melastomataceae that is endemic to the highland rainforest on the island of Taveuni.

It is uniquely Fijian in that it doesn’t grow anywhere else. And it’s what Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum originally wanted depicted on a new flag to replace the “noble banner blue” that has flown over Fiji for half a century since Independence Day, October 10, 1970.

In the year between February 2015 and February 2016, millions of dollars and many thousands of man hours went into making the AG’s wish a reality.

As the government’s communications adviser, I witnessed that effort at first hand. And can provide a fresh insight into the abortive attempt to jettison our national symbol and impose a new one without any consultation with the Fijian people at all.

Not part of the party platform

Changing the flag was not part of the FijiFirst Party’s platform leading up the election on September 17, 2014 that returned Fiji to parliamentary rule. There was no mention of it in the FijiFirst manifesto and it wasn’t canvassed at all in the dozens of speeches I wrote for the Prime Minister leading up to the election. Yet just five months later came the official announcement – which I also wrote – of the proposed flag change and a national competition to find a suitable replacement.

It was a deliberate ploy by the Attorney General not to take the flag change to a popular vote because he knew it would be lost. There was no constituency whatsoever in Fiji pressing for a flag change. In Australia and New Zealand, there have long been organisations and lobby groups specifically dedicated to removing the so called “colonial symbol” of the Union Flag but not in Fiji. So where did the impetus for the flag change come from? The answer is perhaps the most astonishing of the many instances in which Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum has imposed his will on the country. Because he specifically told me that it was to please his father.

The AG revealed to me when the flag change proposal was announced that he had promised his father, Sayed Abdul Khaiyum – who received a 50th Independence anniversary medal last week – that he would change the flag to “remove its colonial symbols” before his father died.

So incredibly, it was one man’s vanity and the power he wields that almost cost the Fijian people their most precious national symbol.

When I say the premise for the flag change was astonishing, it does not reflect the full range of my emotions at the time – including dismay and indignation – when the AG instructed me to sell it to the Fijian people through the Prime Minister’s speeches and statements.

I have precisely the same rights as the AG as a Fijian citizen by birth. But here he was telling me that he was unilaterally changing my own national symbol and that of every other Fijian to please his father.

And without asking me or anyone else whether that was OK with us. Of all the chronic highhandedness and disregard for due process that has come to characterise the FijiFirst government, this certainly took the keke.

Little choice but to carry out wishes

Yet at the time, I had little choice but to carry out his wishes. I did not feel inclined to resign because I suspected even then – rightly as it turned out – that eventually the flag change proposal would fail.

No one man can tell an entire nation that their national symbol is invalid just because he says so. Yet this was the arrogance of Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum.

To this day, I have never understood why the Prime Minister went along with the AG’s proposal. A portrait of Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh still hangs above Voreqe Bainimarama’s office desk in Suva.

And in an interview with me for The Australian in May, 2009, he identified himself as a “Queen’s man”. He even said he would like to see the Queen restored as Queen of Fiji and for the country to again become a monarchy after Sitiveni Rabuka declared a republic in 1987.

“I’m still loyal to the Queen. Many people are in Fiji. One of the things I’d like to do is see her restored as our monarch, to be Queen of Fiji again”, he said. Yet in 2012, Voreqe Bainimarama’s government abolished the official Queen’s Birthday holiday in Fiji and replaced the Queen’s image on Fiji’s banknotes and coins – moves also instigated by the AG.

And in 2015, the Prime Minister took it further, again acceding to the AG’s wishes by agreeing to change the flag that had flown over Fiji for 45 years.

Why? Apart from the obvious inference of no longer being the Queen’s man but the AG’s man, I have never heard a private explanation from the PM for his change of attitude. But I certainly heard plenty from him publicly because I wrote those utterances at the AG’s instigation.

Duly approved messaging

They were cleared by him – as all the PM’s speeches are – and Voreqe Bainimarama duly read out the approved messaging. It was all about Fijians ridding themselves of outdated colonial symbols and embracing “a flag that represents who we are today, rather than our past, and that we can fly proudly as we fulfil our vision to become a modern nation state”.

Right from the start, the AG was keen on the tagimoucia to be the new national symbol. He was drawing his inspiration from the Canadian flag and the maple leaf that replaced the Union Flag on Canada’s national symbol.

But also right from the start, it was obvious to everyone but him that the tagimoucia did not have the same visual impact as the maple leaf. But, of course, It went into the mix anyway because it was the AG’s choice, joining the 22 other designs that emerged from a national competition that eventually drew more than 1400 entries.

The Fijian people may not have had a say on the issue of whether the flag should be changed in the first place. But once they saw the inevitability of that change being railroaded through, many decided that they should at least try to influence the outcome.

The problem was that none of the final designs was sufficiently strong enough to capture the public imagination. They all tended to look like corporate logos for a shipping line.

And the AG’s preferred choice was especially underwhelming. One of the members of the National Flag Committee described it as akin to a used sanitary pad – an observation that may have been lacking in taste but was uncomfortably accurate.

The National Flag Committee was headed by Iliesa Delana, the Para-Olympic Gold Medallist and then Assistant Minister for Youth and Sports and included such community luminaries as Shaenaz Voss from Fiji Airways, the businessman, Dinesh Patel , the then PR consultant and now National Federation Party MP, Lenora Qereqeretabua, and the artist Craig Marlow.

Guided by a technical adviser

Assisting them as technical adviser was a genial American by the name of Ted Kaye– a vexillologist or flag expert from Oregon, who volunteered his services for free and only billed his travelling expenses.

Ted Kaye saw it as his role merely to guide the other members of the panel on the essentials of flag design and insisted that the ultimate choice be Fijian. He later expressed the view that it had been a mistake to present the public with so many choices.

But the essential problem was that none of the designs captured the public imagination. If Fiji was to replace the “noble banner blue”, that design needed to be better than the existing flag and none of them were.

Which was why the desperately-needed excitement factor that might lead to a new symbol being embraced was altogether absent.

The AG and his father detest the current flag because they see on it the symbols of the colonial power, Britain, and both detest the British establishment. During my time in Fiji, the British High Commission made repeated attempts to get the AG to visit the UK but he would always find a reason not to do so.

This is despite the fact that Britons of Indian descent hold senior positions in the British government. Yet time has not dimmed the resentment of Empire on the part of Aiyaz and Sayed Khaiyum, not only Britain’s actions on the Subcontinent during the colonial era but in Fiji.

However much they may be revered in national life, the AG detests Fijian leaders such as Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna and Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, who he regards as stooges of the British who retarded Fiji’s development.

Not hard to identify motive

So it isn’t hard to identify motive in the AG’s desire for a flag change. The issue is whether it is justified. And whether one man – or two men, if you include the Prime Minister – have the right to impose a flag change without consulting the people at all.

I detected no sense of awareness on their part of the irony of returning Fiji to parliamentary democracy in 2014 after nearly eight years of dictatorship and then telling the Fijian people the following year that they would lose their existing national symbol whether they liked it or not.

They had no mandate whatsoever to do it.

At no stage was any thought given to holding a referendum on the issue because they knew they would lose. Which is precisely what happened in Australia and New Zealand when the people were actually consulted.

No change to the flags of either nation and the “Union Jack” still on both, even when they look so similar that the Aussie and Kiwi flags are often confused in a way that Fiji’s can never be because of the distinctive “Fiji blue”.

If Australians and New Zealanders don’t want to change their flags to remove their colonial symbols, why would Fijians? The Fijian people weren’t consulted back in 1987 about whether we supported an end to the monarchy and the switch to a republic. It was merely imposed on us after Sitiveni Rabuka’s coups.

The Fijian people weren’t consulted about removing the Queen’s image from the currency in 2012. And in 2015, the Fijian people weren’t consulted when Voreqe Bainimarama and Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum unilaterally decided to impose a new flag.

Events conspired against flag issue

Yet unfortunately for them – though fortunately for the broad mass of the Fijian people – events conspired against them. The lack of inspiration generated by the 23 flag finalists was already causing mutterings behind the scenes.

When the Prime Minister began to be lobbied heavily by those around him to abandon the idea, he at first acknowledged that not everyone was happy with the designs on offer and said others would be considered.

But then two things happened that sank the flag change altogether.

On February 20 2016, Cyclone Winston slammed into Fiji with winds of more than 300 km/h, killing 44 people and causing damage equal to one third of the country’s GDP. Set against the suffering of Winston, spending any more money on changing the flag was a wasteful extravagance that even the PM and AG recognised.

But then came another more potent factor. The outpouring of national pride that began with Iliesa Delana’s 2012 Para-Olympic gold medal win – with the existing flag at the centre of it all – escalated dramatically when Fiji won its first Olympic gold medal in Rio de Janeiro in August 2016.

Suddenly the “noble banner blue” was everywhere – flown, borne aloft and worn in a manner that conclusively proved its pride of place in the affections of most Fijians. And for the moment at least, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum’s promise to his father to get rid of the hated Union Jack was over.

Six days after the Olympic victory for Fiji’s Rugby Sevens team, I wrote the following statement for the PM, approved by the AG: “It has been deeply moving to witness the way Fijians have rallied around the national flag as our rugby sevens team brought home Olympic gold.

“It has been apparent to the Government since February (because of the cost of Winston) that the flag should not be changed for the foreseeable future”, the statement read.

Decision seen merely as a setback

Yet even then, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum saw the decision as merely a setback and to this day, harbours the same ambition to push a flag change through.

In 2018, he specifically asked me “do you think we can revisit the flag issue for the 50th Independence anniversary?” I laughed it off with a “don’t go there” and the AG said nothing more.

Yet defenders of the “noble banner blue” need to be ready to take up the fight again at the first sign that the AG attempts to again railroad through a change. The steady decline in the FijiFirst government’s electoral fortunes makes it less likely that he will try again but it’s not for a lack of enthusiasm on his part. His promise to his father remains unfulfilled.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Independence, it’s worth thinking about why Fijians love their flag so much. I personally think that in the case of the Union Jack and other colonial symbols on the shield like the British “leopard”, Fijians don’t see these as foreign symbols.

It is OUR flag, Fiji’s flag, not the flag of Great Britain. And with most of the country having grown up with nothing else, let alone never having experienced life in Fiji as a British colony, there’s a sense of collective ownership of the “noble banner blue” that transcends everything else.

These are not symbols of colonial oppression but links with our history – to Fiji’s past. Which also makes them part of our present and which most Fijians want to preserve.

In my experience, anti-British sentiment in Fiji is the preserve of a minority of Fijians of Indian descent – and of a certain generation – who undoubtedly suffered from the racial discrimination and petty apartheid of the colonial era in the 1950s and 60s. These scars are real and cannot be dismissed lightly.

Not the collective experience

But it is not the collective experience of most Fijians and especially the iTaukei, who generally have warm feelings towards Britain, its symbols and the Royal Family, not least because unlike indigenous people elsewhere, they were not dispossessed.

I had wondered how the country would generally respond to the visit to Fiji in 2018 of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. It had been many years since a royal visit. Yet in the event, it was a great success and demonstrated the continuing warm feelings of Fijians towards the Crown.

Plus, of course, the global culture of celebrity that infects young Fijians as much as anyone else.

It all raises an intriguing question. Given what Voreqe Bainimarama said in the interview with me in 2009 about wanting Queen Elizabeth to be Queen of Fiji again, would the monarchy have been restored by the FijiFirst government if it wasn’t for the jaundiced attitude of Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum and his astonishing hold over the PM? Perhaps.

The visit of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle had been such a success that plans were underway for Charles, Prince of Wales, to be in Fiji this weekend for the 50th anniversary celebrations. I had taken it upon myself to make repeated representations to the British in recent years to have Charles and Camilla present, the Prime Minister had issued a formal invitation when he met the Prince in London and plans for the visit were proceeding until the Covid-19 pandemic put a stop to it, as it has most other things.

The symbolism of the Queen’s son in Albert Park on Saturday precisely 50 years to the minute after he stood there in brilliant sunshine on the morning of October 10, 1970 and handed Fiji its instruments of Independence would have been unforgettable.

It would have been history coming full circle not only for Fiji but for the heir to the throne – the direct descendent of Queen Victoria, to whom the chiefs of Fiji ceded Fiji in 1874, present not only for Independence in 1970 but for the fiftieth anniversary of the Fijian nation half a century later. Alas. One of history’s missed opportunities.

Yet there’s someone else who will be in Albert Park on Saturday who I urge everyone present to acclaim. In the lead-up to Independence in 1970, Tessa McKenzie and a man named Robi Wilcox jointly won the national competition for the design of Fiji’s post-Independence flag, incorporating the Union Jack, the shield from the official Coat of Arms and its distinctive sky blue background.

Tessa is now in her mid 80s but still lives in Suva and is still going strong – among other things, a prolific letter writer to the Fiji Times and a staunch defender of the flag she designed. She is a living national treasure and it was wonderful to see her honoured this week among the first group of recipients of the 50th anniversary Independence medal.

So when you see the flag flown, spare a thought for Tessa, the elderly lady in the crowd who deserves to be up there with any queen or princess in the nation’s affections – a living link not only to our past but part of our present and future, like the symbol of our nationhood she devised.

Grubsheet Feejee is the blogsite of Graham Davis, an award-winning journalist turned communications consultant who was the Fiji government’s principal communications adviser for six years from 2012 to 2018 and continued to work on Fiji’s global climate and oceans campaign up until the end of the decade. Other articles here.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz