Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Marcus Banks, Social policy and consumer finance researcher, School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University

In 1988, then federal education minister, John Dawkins, drew upon the politics of class privilege to justify rolling out HECS student loans. A university user-pays system was needed, he argued, because Labor was not in the business of funding “middle-class welfare”. At the time, one reason a neoliberal appeal by Labor to its base could deflate widespread public opposition was that just 7% of working-age Australians held a degree.

Three decades on, Education Minister Dan Tehan is also dog-whistling up the politics of class to cut off the loans system to first-year students who fail half their subjects, ramp up fees for many others, deny JobKeeper to workers in the sector and cut funding.

Dawkins’s representation of the policy problem framed higher education as a bastion of privilege. It relied on the relative absence of working-class students and the irrelevance of higher education to their parents.

For Tehan the problem is represented by these students’ overabundance — particularly in courses that do not produce workers with the specific technical skills he claims are in demand by employers. Tehan’s call to rid the system of failing students is couched in paternalism, a hallmark of the welfare system.Agenda predates COVID

On the surface, a small cohort of students mostly from low socioeconomic backgrounds appear to be the target. Politically, however, it neatly links with the government’s broader restructuring agenda across the campuses. For higher education students and staff alike, it epitomises what the National Union of Students (NUS) president has called a neoliberal way to “incentivise success through fear of punishment”.

The restructuring goes well beyond the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. An explosion of casual employee networks across the country and a recent national assembly of nearly 500 academics voting to build towards unprotected industrial action have boosted campaigning by the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) and NUS against the current cuts and broader restructuring agenda.

Read more: As universities face losing 1 in 10 staff, COVID-driven cuts create 4 key risks

What has changed since 1988?

There are optimistic grounds for thinking that broader societal support is now more likely than in 1988 for this defence of universities as a freely accessible public good.

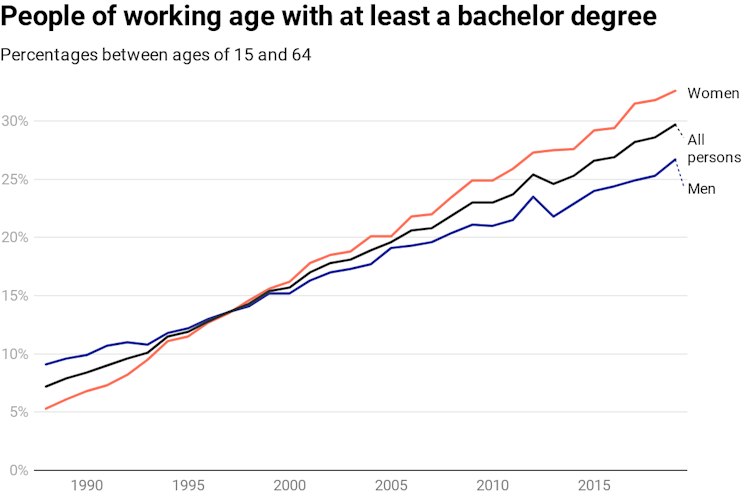

In May 2019, a third of the working-age population (20-64 years) held at least a bachelor degree. That’s almost five times more than in 1988. And nearly two-thirds of this group had a degree, diploma or post-school certificate.

Some 46% of women and 35% of men between the ages of 25 and 34 have a degree. Soon most women in this key working-age cohort will be university graduates, alongside a significant proportion of men.

Social wage has widened

This mainstreaming of university education means the sector joins health and welfare as a core part of the social wage. Australian government spending on keeping the workforce skilled, fit and able to work accounted for more than 60% of its 2019-20 budget. Health-care spending, whether provided by employers (such as US insurance schemes) or more commonly via the state, is in reality part of our wages whether it is paid in cash or kind or goes to workers collectively rather than individually.

The social wage came to prominence in the 1980s as a key part of the Prices and Incomes Accord. The Labor government reached agreement with trade unions and employers that they would trade off wage increases for better social security benefits and progressive education and health reforms. Political economist Elizabeth Humphrys has explained how these trade-offs strengthened the hold of neoliberalism and weakened trade unions.

Read more: Australian politics explainer: the Prices and Incomes Accord

The social wage is the collective part of our overall wages. This understanding provides broad-based, industrial grounds to defend its provision.

Just as it has been unfortunately shown that wage cuts are not stopping job cuts in the university sector, cuts to our social wage are also not in our collective self-interest.

For example, we need to loudly call out that the framing of social security payments as handouts for the poor is a cynical attempt to cultivate “them and us” divisions. In reality, between 2001 and 2015, over 70% of Australian working-age households required income support at some stage. These payments helped smooth the financial risks of unemployment, low wages, caring responsibilities, injury, frailty or disability.

Arguments for the JobSeeker supplement to be kept after the pandemic – such as by the Raise the Rate campaign – are gaining widespread traction.

Read more: Unemployment support will be slashed by $300 this week. This won’t help people find work

A similar basis of mass support exists for campaigns to have equitable, accessible and quality higher education. Secondary school students and their parents, casualised and ongoing staff and the wider trade union movement all have a stake in rejecting the current round of university cuts and restructuring. Higher education is now firmly part of our social wage, and we must defend it.

– ref. Do Australians care about unis? They’re now part of our social wage, so we should – https://theconversation.com/do-australians-care-about-unis-theyre-now-part-of-our-social-wage-so-we-should-144798