Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Greg Barton, Chair in Global Islamic Politics, Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University

Have we flattened the curve of global terrorism? In our COVID-19-obsessed news cycle stories about terrorism and terrorist attacks have largely disappeared. We now, though, understand a little more about how pandemics work.

And ironically, long before the current pandemic, the language of epidemiology proved helpful in understanding by analogy the way in which terrorism works as a phenomenon that depends on social contact and exchange, and expands rapidly in an opportunistic fashion when defences are lowered.

Terrorism goes quiet – but we’ve seen this before

In this pandemic year, it appears one piece of good news is that the curve of international terrorist attacks has indeed been flattened. Having lost its physical caliphate, Islamic State also appears to have lost its capacity, if not its willingness, to launch attacks around the world well beyond conflict zones.

We have seen this happen before. The September 11 attacks in 2001 were followed by a wave of attacks around the world. Bali in October 2002, Riyadh, Casablanca, Jakarta and Istanbul in 2003, Madrid in March 2004, followed by Khobar in May, then London in July 2005 and Bali in October, not to mention numerous other attacks in the Middle East and West Asia.

Since 2005, with the exception of the Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris in January 2015, al-Qaeda has been prevented from launching any major attacks in western capitals.

The September 11 attacks precipitated enormous investment in police counterterrorism capacity around the world, particularly in intelligence. The result has been that al-Qaeda has struggled to put together large-scale coordinated attacks in Western capitals without being detected and stopped.

Then in 2013, Islamic State emerged. This brought a new wave of attacks from 2014 in cities around the world, outside of conflict zones in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and Nigeria.

This wave of IS international terror attacks now appears to have reached an end. The hopeful rhetoric of the collapse of the IS caliphate leading to an end of the global campaign of terror attacks appears to have been borne out. Although, as the sophisticated and coordinated suicide bombings in Colombo in Easter 2019 reminded us, further attacks by previously unknown cells cannot ever be ruled out.

While it’s tempting to conclude that the ending of the current wave of international terrorist attacks by IS is due largely to the ending of the physical caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and a concomitant collapse of capacity, the reality is more complex. Just as the wave of al-Qaeda attacks in the first half of the 2000s was curtailed primarily by massive investments in counterterrorism, so too it appears to be the case with IS international terror plots in the second half of this decade.

Read more: Why we need to stay alert to the terror threat as the UK reopens

The 2019 attacks in Sri Lanka illustrate dramatically what happens when there is a failure of intelligence, whether due to capacity or, as appears to be the case in Sri Lanka, a lack of political will. The rise of IS in 2013-14 should not have caught us by surprise, but it did, and in 2014 and 2015 we were scrambling to get up to speed with the intelligence challenge.

Epidemiology of terror

The parallels with the epidemiology of viruses are striking. Reasoning by analogy is imperfect, but it can be a powerful way of prompting reflection. The importance of this cannot be underestimated as intelligence failures in counterterrorism, like poor political responses to pandemics, are in large part failures of imagination.

We don’t see what we don’t want to see, and we set ourselves up to become victims of our own wishful thinking. So, with two waves of international terrorist attacks over the past two decades largely brought under control, what can we say about the underlying threat of global terrorism?

There are four key lessons we need to learn.

First, we are ultimately seeking to counter the viral spread of ideas and narratives embodied in social networks and spread person-to-person through relationships, whether in person or online. Effective policing and intelligence built on strong community relations can dramatically limit the likelihood of terrorist networks successfully executing large-scale attacks. Effective intelligence can also go a long way to diminishing the frequency and intensity of lone-actor attacks. But this sort of intelligence is even more dependent on strong community relations, built on trust that emboldens people to speak out.

Second, terrorist movements, being opportunistic and parasitic, achieve potency in inverse relation to the level of good governance. In other words, as good governance breaks down, terrorist movements find opportunity to embed themselves. In failing states, the capacity of the state to protect its citizens, and the trust between citizen and authorities, provides ample opportunities for terrorist groups to exploit grievances and needs. This is the reason around 75% of all deaths due to terrorist activity in recent years have occurred in just five nations: Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria (followed by Somalia, Libya, and Yemen).

The third lesson is directly linked to state failure, and is that military methods dramatically overpromise and under-deliver when it comes to countering terrorism. In fact, more than that, the use of military force tends to generate more problems than it solves. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than what has been so wrongly framed as the Global War on Terror.

Beginning in October 2001 in the immediate wake of the September 11 attacks, the war on terror began with a barrage of attacks on al-Qaeda positions in Afghanistan. It was spurred by understandable anger, but it led to two decades of tremendously expensive military campaigns they have completely failed to deliver the hoped-for end in terrorism to justify the massive toll of violence and loss of life.

The military campaign in Afghanistan began, and has continued for almost 19 years, without any strategic endpoints being defined and indeed with no real strategy vision at all. After almost two decades of continuous conflict, any American administration would understandably want to end the military campaign and withdraw.

Obama talked of doing this but was unable to do so. Trump campaigned on it as one of the few consistent features of his foreign policy thinking. Hence the current negotiations to dramatically reduce American troop numbers, and in the process trigger a reduction in allied coalition troops while releasing thousands of detained militants in response to poorly defined and completely un-guaranteed promises of a reduction in violence by the Taliban.

This is America’s way of ending decades of stalemate in which it is has proven impossible to defeat the Taliban, which even now controls almost one half of Afghanistan. But even as the peace negotiations have been going on the violence has continued unabated. The only reason for withdrawing and allowing the Taliban to formally take a part in governing Afghanistan is fatigue.

Not just Afghanistan

If the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan were the main story, the situation would already be far more dire then we would care to accept. But the problem is not limited to Afghanistan and West Asia. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 by the “coalition of the willing” was justified largely on the grounds it was necessary to stop al-Qaeda from establishing a presence in Iraq. It achieved, of course, the exact opposite.

Al-Qaeda had little, if any, presence in Iraq prior to the invasion. But the ensuring collapse of not just the regime of Saddam Hussein but the dismantling of the Baath party and the Iraqi military, led largely by a Sunni minority in a Shia majority country, created perfect storm conditions for multiple Sunni insurgencies.

These in turn came to be dominated by the group that styled itself first as Al Qaeda in Iraq, then as the Islamic State in Iraq, and then as the Islamic state in Iraq and Syria. This powerful insurgency was almost completely destroyed in the late 2000s when Sunni tribes were paid and equipped to fight the al-Qaeda insurgency.

The toxic sectarian politics of Iraq, followed by the withdrawal of US troops at the end of 2011, coinciding with the outbreak of civil war in Syria, saw the almost extinguished insurgency quickly rebuild. We only really began to pay attention when IS led a blitzkrieg across northern Iraq, seized Mosul, and declared a caliphate in June 2014.

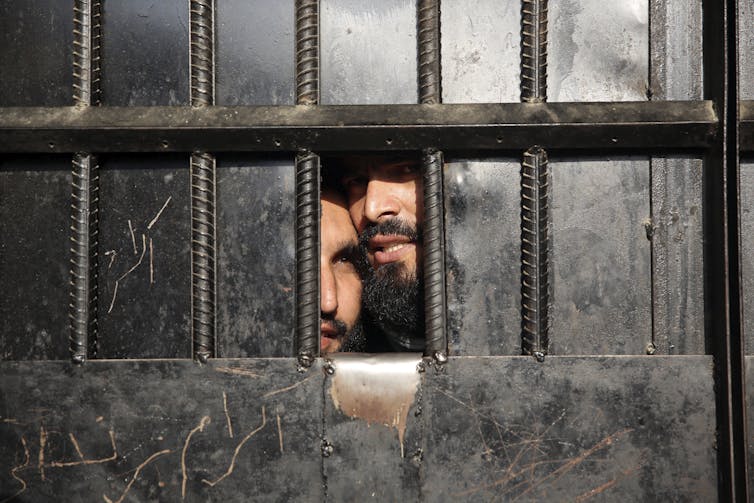

Defeating this quasi-state took years of extraordinarily costly military engagement. But even as IS was deprived of the last of its safe havens on the ground, analysts were warning it continued to have tens of thousands of insurgent militants in Syria and northern Iraq and was successfully returning to its earlier mode of insurgency.

Read more: US retreat from Syria could see Islamic State roar back to life

As the Iraqi security forces have been forced to pull back in the face of a steadily building COVID-19 pandemic, there are signs the IS insurgent forces have continued to seize the spaces left open to them. Even without the pandemic, the insurgency was always going to steadily build strength, but the events of 2020 have provided it with fresh opportunities.

The fourth and final lesson we need to come to terms with is that we are dealing with a viral movement of ideas embodied in social networks. We are not dealing with a singular unchanging enemy but rather an amorphous, agile, threat able to constantly evolve and adapt itself to circumstances.

Al-Qaeda and IS share a common set of ideas built around Salafi-jihadi violent extremism. But this is not the only violent extremism we have to worry about.

In America today, as has been the case for more than a decade, the prime terrorist threat comes from far-right violent extremism rather than from Salafi-jihadi extremism. The same is not true in Australia, although ASIO and our police forces have been warning us far-right extremism represents an emerging secondary threat.

But the potent violence of an Australian far-right terrorist in the attack in Christchurch in March 2019 serves to remind us this form of violent extremism, feeding on toxic identity politics and hate, represents a growing threat in our southern hemisphere.

Read more: ASIO chief’s assessment shows the need to do more, and better, to prevent terrorism

Fighting the terrorist pandemic

In this year in which we have been, understandably, so preoccupied with the coronavirus pandemic, another pandemic has been continuing unabated. It is true we have successfully dealt with two waves of global terrorist attacks over the past two decades, but we have not dealt successfully the underlying source of infections.

In fact, we have contributed, through military campaigns, to weakening the body politic of host countries in which groups like al-Qaeda, IS and other violent extremist groups have a parasitic presence.

We now need to face the inconvenient truth that toxic identity politics and the tribal dynamics of hate have infected western democracies. Limiting the scope for terrorist attacks is difficult. Eliminating the viral spread of hateful extremism is much harder, but ultimately even more important.

– ref. In COVID’s shadow, global terrorism goes quiet. But we have seen this before, and should be wary – https://theconversation.com/in-covids-shadow-global-terrorism-goes-quiet-but-we-have-seen-this-before-and-should-be-wary-144286