Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mark Evans, Professor of Governance and Director of Democracy 2025 – bridging the trust divide at Old Parliament House, University of Canberra

Australians have exhibited high levels of trust in federal government during the coronavirus pandemic, a marked shift from most people’s views of government before the crisis began, new research shows.

Australians are also putting their trust in government at far higher rates than people in three other countries badly affected by the virus – the US, Italy and the UK.

The findings, published today in a new report, “Is Australia still the lucky country?”, are part of a broader comparative research collaboration between the Democracy 2025 initiative at the Museum of Australian Democracy and the TrustGov Project at the University of Southampton in the UK.

The research involved surveys of adults aged between 18 and 75 in all four countries in June to gauge whether public attitudes toward democratic institutions and practices had changed during the pandemic. We also asked about people’s compliance with coronavirus restrictions and their resilience to meet the challenge of the post-pandemic recovery.

The main proposition behind our research is that public trust is critical in times like this. Without it, the changes to public behaviour necessary to contain the spread of infection are slower and more resource-intensive.Read more: Coronavirus spike: why getting people to follow restrictions is harder the second time around

Levels of trust higher for most institutions

Australians are now exhibiting much higher levels of political trust in federal government (from 25% in 2019 to 54% in our survey), and the Australian public service (from 38% in 2018 to 54% in our survey).

Compared to the other three countries in our research, Australia’s trust in government also comes out on top. In the UK, only 41% of participants had high trust in government, while in Italy it was at 40% and the US just 34%.

Confidence in key institutions

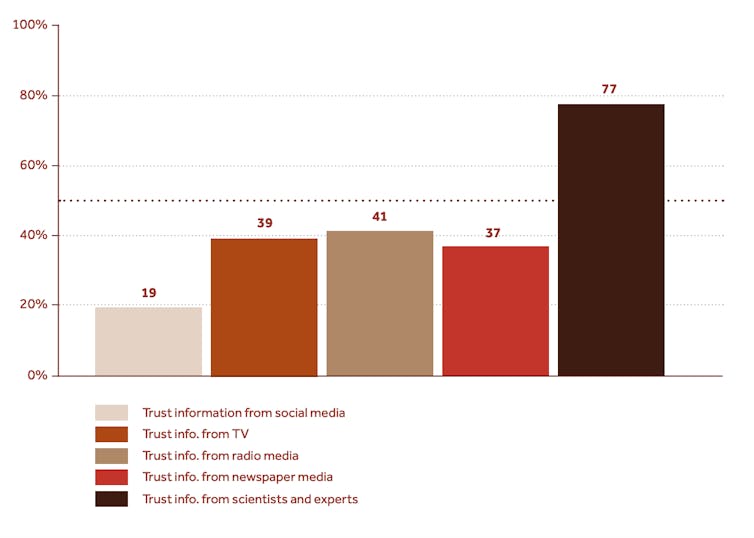

Australians also have high levels of confidence in institutions related to defence and law and order, such as the army (78%), police (75%) and the courts (55%). Levels of trust are also high in the health services (77%), cultural institutions (70%) and universities (61%). Notably, Australians exhibit high levels of trust in scientists and experts (77%).

These figures were comparable with the other countries in the survey, with the notable exception of Americans’ confidence in the health services, which stood at just 48%.

Although Australians continue to have low levels of trust in social media (from 20% in 2018 to 19% in our survey), confidence is gaining in other forms of news dissemination, such as TV (from 32% in 2018 to 39%), radio (from 38% in 2018 to 41%) and newspapers (from 29% in 2018 to 37%).

Public trust in various media, scientists and experts

How does Morrison compare with Trump and other leaders?

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is perceived to be performing strongly in his management of the crisis by a significant majority of Australians (69%).

Indeed, he possesses the strongest performance measures in comparison with Italy (52% had high confidence in Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte), the UK (37% for Prime Minister Boris Johnson) and the US (35% for President Donald Trump).

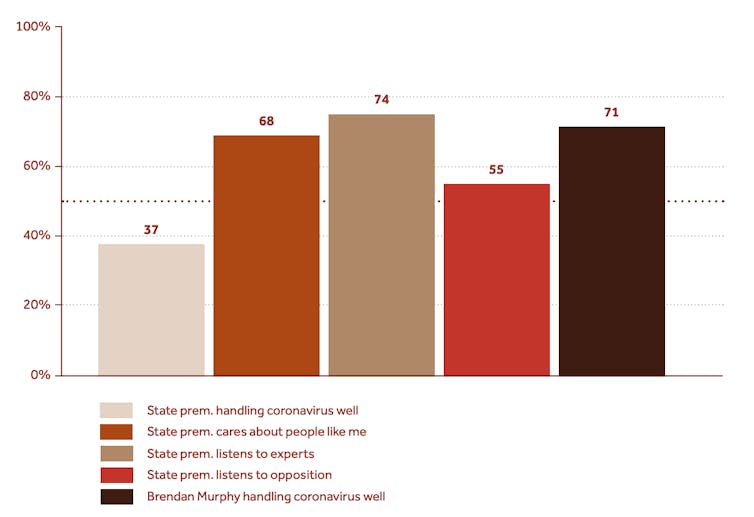

Morrison also scores highly when it comes to listening to experts, with 73% of Australians saying he does, compared to just 33% of Americans believing Trump does.

Public perceptions of leadership

Interestingly, Morrison’s approval numbers are also far higher than the state premiers in Australia. Only 37% of our respondents on average think their state premier or chief minister is “handling the coronavirus situation well”. Tasmanians (52%) and Western Australians (49%) had the highest confidence in their leaders’ handling of the crisis.

This suggests that in Australia, the politics of national unity (the “rally around the flag” phenomenon) is strong in times of crisis, whereas people tend to view the leaders of states or territories as acting in their own self-interest.

Perceptions of the quality of state and territory leadership

Compliance and resilience

Our findings also showed most Australians were complying with the key government measures to combat COVID-19, but were marginally less compliant than their counterparts in the UK. (Australians are relatively equal with Italians and Americans.)

Among the states and territories, Victorians have been the most compliant with anti-COVID-19 measures, while the ACT, Tasmania and the Northern Territory were the least compliant. This is in line with the low levels of reported cases in these jurisdictions and by the lower public perception of the risk of infection.

When it comes to resilience to meet the challenges of the post-pandemic recovery, we considered confidence in social, economic and political factors.

Although a majority of Australians (60%) expect COVID-19 to have a “high” or “very high” level of financial threat for them and their families, they are less worried than their counterparts in Italy, the UK and US about the threat COVID-19 poses “to the country” (33%), “to them personally” (19%), or “to their job or business” (29%).

Perceptions of the level of threat posed by COVID-19

About half of all Australians believe the economy will get worse in the next year (this is slightly higher than in the US but much lower than in the UK and Italy). In Australia, women, young people, Labor voters and those on lower incomes with lower levels of qualifications are the most pessimistic on all confidence measures.

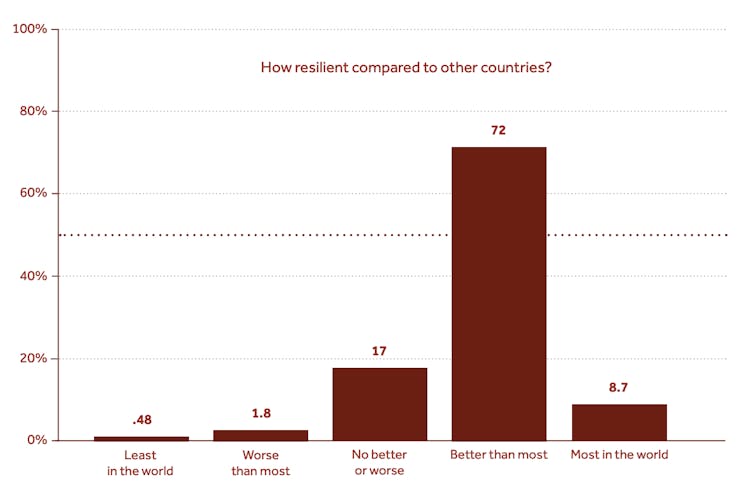

However, Australians remain highly confident the country will bounce back from COVID-19, with most believing Australia is “more resilient than most other countries” (72%).

Perceptions of Australian resilience

We also assessed whether views about how democracy works should change as a result of the pandemic. An overwhelming majority of people said they wanted politicians to be more honest and fair (87%), be more decisive but accountable for their actions (82%) and be more collaborative and less adversarial (82%).

Staying lucky

Australia has been lucky in terms of its relative geographical isolation from international air passenger traffic during the pandemic.

But Australia has also benefited from effective governance – facilitated by strong political bipartisanship from Labor – and by atypical coordination of state and federal governments via the National Cabinet.

The big question now is whether Morrison can sustain strong levels of public trust in the recovery period.

Read more: A matter of trust: coronavirus shows again why we value expertise when it comes to our health

There are two positive lessons to be drawn from the government’s management of COVID-19 in this regard.

First, the Australian people expects their governments to continue to listen to the experts, as reflected in the high regard that Australians have for evidence-based decision-making observed in the survey.

Second, the focus on collaboration and bipartisanship has played well with an Australian public fed up with adversarial politics.

The critical insight then is clear: Australia needs to embrace this new style of politics – one that is cleaner, collaborative and evidence-based – to drive post-COVID-19 recovery and remain a lucky country.

– ref. Australians highly confident of government’s handling of coronavirus and economic recovery: new research – https://theconversation.com/australians-highly-confident-of-governments-handling-of-coronavirus-and-economic-recovery-new-research-142904