Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Rosemary Jean Kennedy, Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture and Urban Design, Queensland University of Technology

Retirement villages – walled, gated and separate seniors’ enclaves – have had their day. The word “retirement” is redundant and engagement between people of all ages is high. That’s how participants in the Longevity By Design Challenge envisage life in Australia in 2050.

Their challenge was to identify ways to prepare and adapt Australian cities to capitalise on older Australians living longer, healthier and more productive lives. Their vision, outlined in this article, offers a positive contrast to much of the commentary on “ageing Australia”.

Read more: We’re not just living for longer – we’re staying healthier for longer, too

We have been repeatedly warned about a looming “crisis” when by 2050 one in four Australians will be 65 or older. They have been portrayed as dependent non-contributors, unable to take care of themselves. This scenario of doom is based on underlying assumptions that everyone over 65 wants to, can or should stop any kind of productive contribution to Australia.

What if these assumptions are wrong?

The longevity bonus

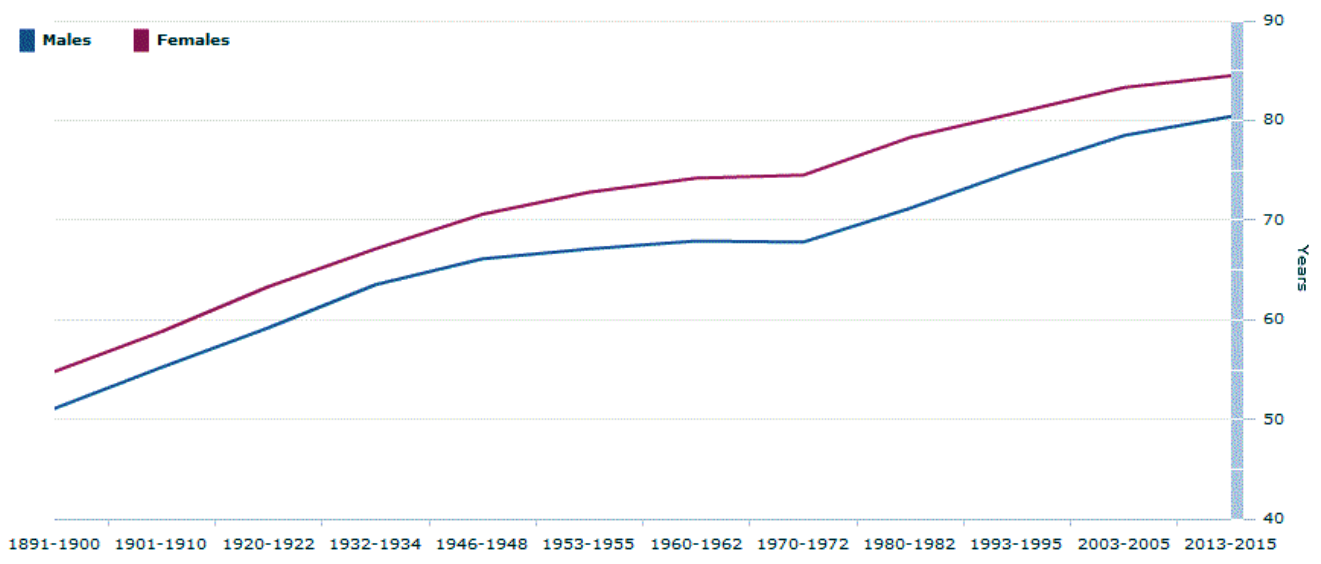

Australians’ average life expectancy is well into our 80s. That represents a 30-year longevity “bonus” since the Age Pension was introduced in 1909 when average life expectancy was 55.

Increases in the average life expectancy of Australian men and women since 1890. Australian Bureau of Statistics, CC BY

Read more: Retiring at 70 was an idea well ahead of its time

Now, older people are healthier, working for longer – whether paid, volunteering, flexible, part-time, full-time or launching start-ups – or are in learning programs. By 2030 all of the baby boomers will have turned 65. At this time Generation X will start their contribution to the expanding older cohort.

Australian society will be better positioned to navigate this future if we make the most of the significant opportunities baby boomers present. They are living much longer, want to remain productive and engaged throughout their adult lives, and have a valuable cache of knowledge and skills.

One way to support economic and social participation is to reconsider the factors – physical, regulatory and financial – that determine how our buildings, suburbs and streets are organised.

Conventional urban development models rely on short-term development finance. It delivers suburban cities of individual houses with a need for private transportation. For many households (not just seniors) distance and lack of mobility are barriers to participation, resulting in isolation and loneliness.

Read more: 1 million rides and counting: on-demand services bring public transport to the suburbs

Making the most of life after 65

The Longevity by Design Challenge brought new perspectives to preparing and adapting Australian cities to capitalise on the “longevity” phenomenon over coming decades. The challenge asked:

How do we best leverage the extra 30 years of life and unleash the social and economic potential of people 65+ to contribute to Australia’s prosperity?

In February 2020, 121 professionals (of all ages) from 60 built environment design and senior living organisations, along with several older people, took part in the challenge. They explored how baby boomers will change the landscape of living, learning, working and playing. Sixteen cross-disciplinary creative teams considered what longevity could look like in this new environment in which buildings and neighbourhoods are remade.

Good design begins with people. Together the participants concluded that designing for older people is actually “inclusive design”. Everyone wants the same things for a good life: autonomy and choice, purpose, family and friends, good health and financial security.

Read more: From 8 to 80: designing adaptive spaces for an ageing population

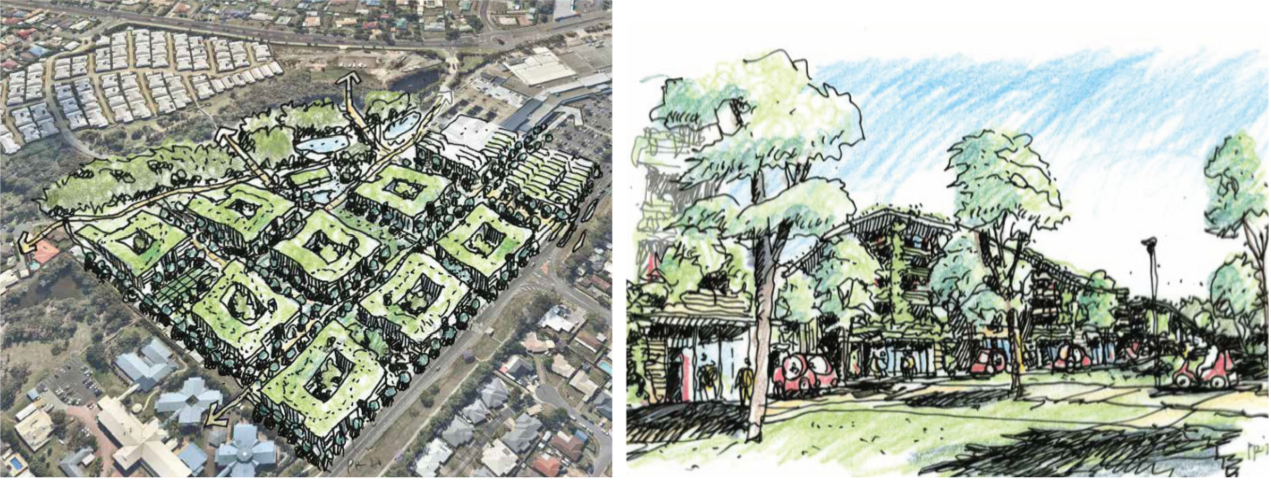

Teams were presented with one of three locations representing typical middle and outer suburbs. They were challenged to transform buildings and neighbourhoods to make the most of longevity opportunities.

The teams used principles of social and physical connectedness with the aim of increasing choices and improving circumstances for people at all stages of life. Key design priorities were “mix” – of places, uses, people and generations – and “heart”, which placed people at the centre of the narrative.

Suggested approaches included:

- building walkable neighbourhoods that reduce distances between homes and services

- converting typical house blocks to “super blocks” where multiple generations can live

- adopting finance development models using long-term capital, rather than short-term debt, for greater financial and community returns.

Neighbourhoods could be retrofitted over 30 years. This would require changes to local government planning codes and innovations by the finance sector.

Other teams designed interconnected environments using links between natural, built and technological assets. They designed spaces to enable people over 65 to continue to make creative and productive contributions.

By creating inclusive infrastructure, such as closely connected living and learning “micro-neighbourhoods”, people of all ages remain the “heart” of the economic, social and cultural life of communities. A mobility “ecosystem”, including automated buses and electric ride sharing, could connect specialist knowledge and skill centres to local hubs.

Making inclusive neighbourhoods happen

While autonomous vehicle technology might provide more equal access to mobility and transportation, the designers warned that transforming conventional settings of houses and cars to walkable neighbourhoods and autonomous vehicles will be gradual. It depends on two things:

- urban planning that ensures everyone has good access to safer transport alternatives rather than traffic-centric layouts

- long-term equity financed by “future-focused” lenders.

In this model, lenders are less focused on short-term returns. Instead, they have a greater focus on quality design as a catalyst for more development. In a virtuous circle, attractive development that places people close to community activities and businesses generates greater “footfall”. That in turn creates more business opportunities that make financially viable communities.

The Longevity by Design Challenge identified a range of opportunities to create a vibrant “longevity” economy by including people of all ages. Small, incremental and affordable changes towards resilient and age-friendly communities can transform perceived burdens into real assets.

Planning communities to embrace, not exclude, people over 65 has all kinds of benefits for Australia.

– ref. Retire the retirement village – the wall and what’s behind it is so 2020 – https://theconversation.com/retire-the-retirement-village-the-wall-and-whats-behind-it-is-so-2020-135953